Michael Crane arrived at Augusta a rising star, his video-editing skills sought for every big sporting event on TV. He left in a cop car, high and headed to jail for an audacious robbery.

Michael Crane was no golfer. But he did dream of a star turn at the Masters, a chance to show off his handiwork and skill, a culmination of years of practice. And in April 2007 his chance arrived: At 31 he was handpicked to work one of the most-watched broadcasts on the sports calendar.

A freelance TV editor, Crane specialized in quick-cutting highlight packages that played within event broadcasts—the type that would embroider any big game—and his career was flourishing. That year alone, he recalls having already worked the Super Bowl, the Final Four and more than a dozen other events. Now he would be venturing to the most exalted golf course in the U.S., working for CBS on its commercial-free broadcast of “a tradition unlike any other.”

Yet here it was, the Monday morning of Masters week, and instead of focusing on Augusta National’s greens and, ultimately, the green jacket, Crane was fixated on a different color: red. As in the red dye spurting over his hands and tracing an arc, before splashing onto his rented Chevy Monte Carlo. An exploding cartridge, he would later realize, had been placed in the pile of bills handed to him by a teller at the Augusta bank he had just robbed with two strangers.

Clutching a wad of cash, a look of horror setting in, Crane figured, quite rightly, that he would not be making the final cut at the Masters, after all.

* * *

When Young Michael Crane was asked what he wanted to do when he grew up, reflexively, he would reply: Play in the NFL. Or work for ESPN. His father, an electrician in rural Warrior, Ala., a half hour north of Birmingham, suggested the boy come up with more plausible career choices. The son persisted.

Overcoming a deficit of size (5' 9", 160 pounds) with a surplus of heart, Crane was a running back and an all-state defensive back at Corner High. After one season playing at what is now Western Alabama (in Division II) he quit, in part because of homesickness and in part because he’d married and had a son on the way. His NFL ambitions at an end, he appeared to have abandoned his ESPN aspirations when he took an entry-level job in statement processing at a SouthTrust Bank in Birmingham.

Crane, then 22, spent a few months at that soulless desk job before he got his first break: A friend offered him some freelance work, first shooting, then producing and editing, at a TV startup, College Sports Southeast. He quit his bank job the next week. He’d take any gig in sports TV; if that meant shooting a football game in the rain or getting up in the wee hours to make a kickoff in Kentucky that afternoon—well, what’s 400 miles? “I was making about $18,000,” Crane says, “and I told my wife that if I could get to $30,000, that would be awesome.”

A year or so later, Crane was freelancing at the Great Outdoor Games in Lake Placid, N.Y., when someone asked whether he knew how to operate an EVS machine. “Sure,” he said. Then he asked around: Does anyone know what the hell an EVS is? Crane stayed up all night in his hotel room, reading the manual for a video-editing apparatus that pulls short clips from multiple cameras. By the next day he was at least semiconversant. “It was the ultimate in fake it till you make it,” he says. “I was just hoping I could power up the machine, but it went well.”

Crane didn’t just pick it up quickly; he was a natural, a virtuoso. The equipment—about the size of a laptop, with various dials and levers and buttons—almost came to seem an extension of his arm. Pairing his feel for sports with his dexterity as an editor, he could put together an in-game highlights package in a matter of seconds. If a running back, say, rushed for 100 yards in a half, Crane would pull video from various “looks” and fashion a 20- or 30-second clip of the best runs. “You want the highlights to seem natural, to tell the same story that’s playing out live,” Crane says, “That’s what really good guys who run tape do.”

Pick a big sports moment. Most fans will be able to picture it; they’ll also remember the TV announcer who called it, Al Michaels or Dick Vitale or Joe Buck. The “talent,” though, is only a small part of an ecosystem that is equal parts army and hospital. So-called below-the-line guys—and the vast majority of workers in sports broadcasting remain men—are every bit as responsible for your enjoyment of the game as the folks sitting in hair and makeup. These anonymous operatives in the production truck can make or break a broadcast.

And inside that community word travels fast. Within a year and a half of his introduction to the EVS, Crane’s skills were an open secret. He was a man in demand. “Michael had an innate ability to see things,” says Bob (Rossi) Rosburg, a longtime network sports producer who worked tennis events with Crane in the 2000s, “and, more importantly, to present them in meaningful ways.”

Crane’s dream of working at ESPN? Heck, he’d already worked football and basketball games for the network. Here he was, still in his mid-20s, and John Madden—in the booth for Monday Night Football and in need of quick highlights for his famed telestrator—was asking for him by name. CBS hired him to freelance the NCAA tournament. Golf Channel and Tennis Channel tried to book him the same week. The Grizzlies’ broadcast team enlisted his services, offering him a seat on their plane. In April 2004, Crane worked a tennis tournament for ESPN in Charleston, S.C. Before the week was over a producer asked, “Do you speak French?”

“No,” Crane responded, perplexed. “Why?”

“Because you’re damn good, and we need you in Paris next month to work the French Open.”

Later that summer NBC would send Crane to the Athens Olympics, making for a blistering several weeks of work. “It was nuts,” he recalls. “One minute it would be water polo and the next it would be volleyball.” In part because of his deft handiwork, the network’s coverage at the Games received an Emmy.

Not yet 30, the self-described “Alabama kid” with a hickory-basted drawl was “living the effing life,” he says, making $700 a day before overtime and a per diem, and working 250 days a year. “The only reason it wasn’t more,” he says, “was because I had to turn down jobs.” He was “making national pay,” he notes, “and, remember, I’m living in Alabama.”

The dream came at a price. His marriage fell apart—Crane was in Athens when he asked for a divorce—and all the travel kept him from seeing his son and new daughter as much as he’d like. Still, at his 10th high school reunion he could regale classmates with stories from the road, and he could afford to be quick in throwing down his credit card when his colleagues repaired to the bar at the end of a broadcast.

Like so many of his coworkers, Crane got a rush from the job. If on-air announcers projected calm and authority, the vibe in the truck was the exact opposite, a hive of frenetic energy. It wasn’t simply that live sports are unscripted, unchoreographed, subject to sudden change. It was the knowledge that an audience of millions was about to consume his work.

The stress and the exhilaration, though, were compounded by erratic hours and erratic travel. Crane was working at Wimbledon in 2004 when rain delays threw off his work schedule. By the time the tournament ended he had to fly directly to the Great Outdoor Games in Reno, eight time zones away, and hit the ground running. “Twelve Red Bulls got me through it,” he says. “I was in the truck bouncing off the walls.”

Eventually the natural highs of the job—to say nothing of caffeine-and-taurine-propelled ones—gave way to dark lows. Crane says he did his share of heavy drinking, but cocaine quickly became his drug of choice. He developed a sixth sense for where to find it, sussing out dealers in hotel lobbies, strip clubs and dive bars. More times than he can recall he would show up to work after a sleepless night, still high. “I don’t know,” he says, “if I was hiding [my use] well or not.”

To which coworkers say: yes and no. Brad Douglas, an EVS producer who often worked alongside Crane, including at that 2004 French Open, remembers him showing up late for a shift in Paris, his eyes rimmed in red, two Coca-Colas in one hand and two bags of chips in the other. Douglas recalls thinking, Do what you want in your downtime, but when it affects the broadcasts we’re going to have a problem. And that never happened. “I couldn’t believe what he was doing,” Douglas says. “He could whip together 10 clips and make a highlight package during a commercial break. Audio? Perfect. Timing? On the money. Not one mistake. “You had an uncomfortable feeling that things could go south for him at any moment—but as far as his work, he was a savant.”

* * *

This is what "south" looked like for Michael Crane.

Around 4 p.m. on Sunday, April 1, 2007, he checked into his room at the Augusta Holiday Inn on Gordon Highway, on the west side of town. Then, with half a day to kill before his first production shift, he went about scrounging up a fix. He found a pair of local dealers and invited them back to his room, where he quickly blew through $1,500 on coke and crack. In Crane’s words: It was “an all-night party.”

That party ended the next morning only because he had run out of money. (It might have gone longer, Crane says, had he not let the dealers indulge from their own stash.) Crane didn’t have an ATM card to get more cash. So he made a suggestion that—in his haze, anyway—seemed brilliant: Why not knock off a bank?

In no shape to drive, he gave his dealers the keys to his rental car and jumped in the back seat. The three men headed to a Wachovia branch a few minutes down the highway, six miles from Augusta National. (Three years earlier Wachovia had bought SouthTrust Bank, Crane’s first employer.)

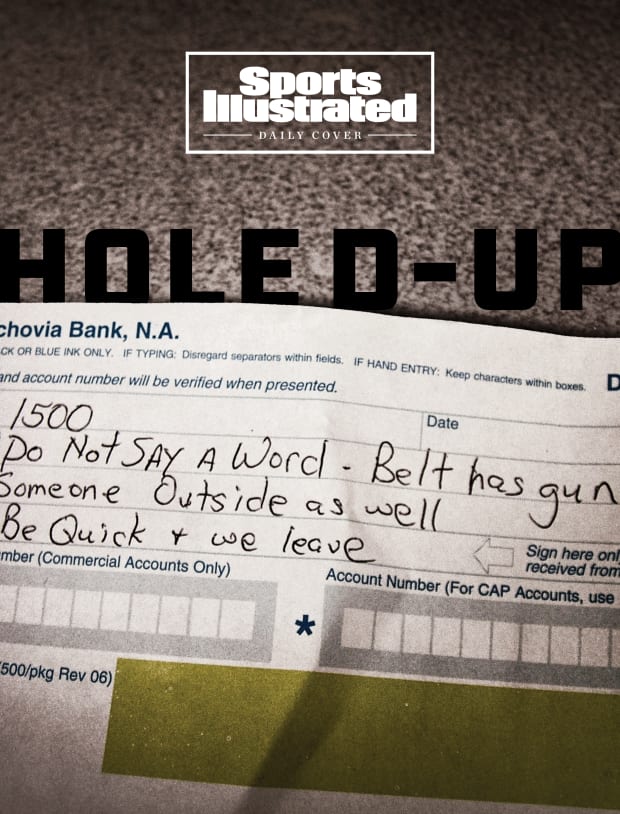

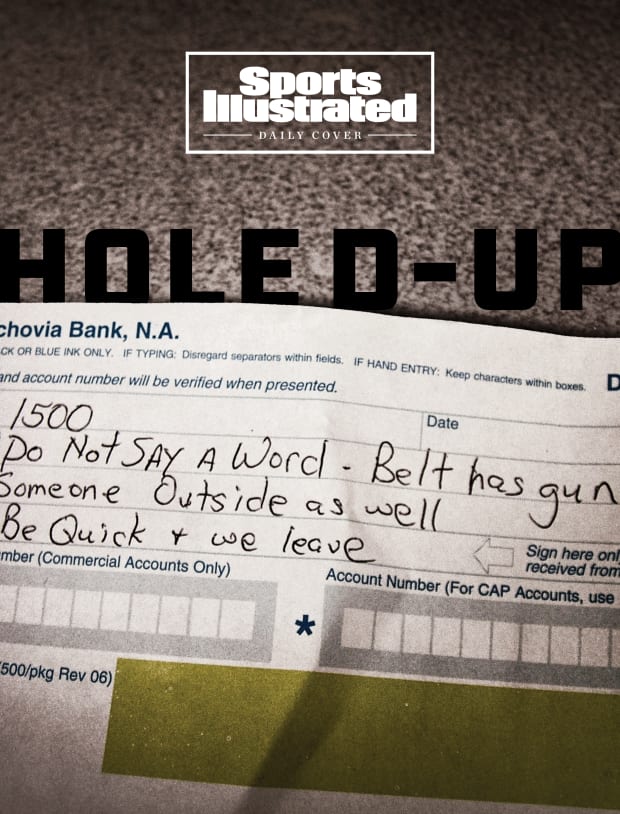

At 9 a.m.—one hour before he was supposed to arrive at work, just as the bank opened—Crane walked through the front door, unarmed and wearing no mask, while the dealers waited in the car. Under his Atlanta Braves visor his face was clearly visible to surveillance cameras. He grabbed a deposit ticket and on the front scribbled a demand for $1,500, claiming to have a gun. Do not say a word. . . . Someone outside as well. . . . Be quick and we leave. Then he presented the note. More confused than scared, the teller asked, “Are you sure you want to do this?”

Crane wasn’t—but he said yes anyway. The teller handed over a stack of bills, inside of which was a packet of distance-activated exploding dye. And just as Crane reached his car, a few hundred feet away from the front exit, the packet exploded. “Holy s---!” came the chorus from the three robbers.

As police cruisers rolled up to the bank, the conspirators sped off, heatedly discussing their next move. When they got back to the Holiday Inn, the dealers split. For Crane, the possibility of missing his shift at the Masters was suddenly the least of his concerns.

The cocaine fog having lifted as the gravity of the situation set in, he figured there was no use in running. He walked to the hotel courtyard, sat on a bench and phoned the Augusta police. When the dispatcher picked up, Crane said words to the effect of: “I know who robbed that Wachovia Bank. He’s staying at the Holiday Inn.”

Crane recalls being overcome by a wicked cocktail of emotions—shame, embarrassment, fear, self-loathing. But perhaps most prominent was relief. He knew he had been out of control for years. “Drugs wear you down, and I was so tired,” he says. “Tired physically, but also tired of screwing up and making bad decisions.”

Lighting a cigarette, he waited for the cops to come arrest him. He confessed to the crime on the spot, took full responsibility over his accomplices and offered to answer any questions. (The two dealers were picked up at the nearby Augusta Super Inn later that day. Their charges were dropped.)

One year earlier, the big scandal from Augusta before play started had been about a 26-year-old man who fired a gun at the courtesy car assigned to golfer Tom Lehman. The guy from the broadcast team who tried to jack a local bank was a whole new level of outré pretournament news. While word of Crane’s arrest—and the bizarre circumstances—rocketed around the television compound, he was booked at Richmond County Jail on a robbery charge.

Then he made one last error: He declared himself a suicide risk, hoping he would be put in a cell by himself. The intake officer took all of Crane’s personal possessions, including his clothes, and assigned him to a room with six other men who were also deemed dangers to themselves.

Crane had expected to spend the week at perhaps the most pristine and dignified enclave in sports. Instead, as Zach Johnson was being feted on Sunday and fitted with a green jacket, Crane was 13 miles away, sharing, he says, a cell with a half-dozen other naked accused felons.

* * *

After pleading guilty that October to bank robbery by force and intimidation, Crane was sentenced to 37 months—the recommended minimum—at a federal correction facility in Talladega. He was despondent about his plight until a cellmate summoned him. “He says, ‘Michael, get in here. I want to show you something. Bring your paperwork,’ ” Crane recalls. “He goes, ‘See your release date? . . . Let me show you mine.’ He pulls it out. It says: death. After that I stopped moping.”

Sports also helped Crane get through what “seemed like an eternity” in prison. He could hold his own on a softball field and on a basketball court, but his line of work gave him real currency among the inmates. He could rattle off stories from the Super Bowls he’d worked and the times he’d flown on an NBA team’s charter. Eventually, he could also joke about the felonious misadventure in Augusta. His go-to setup line before launching into an account of his saga: “One year at the Masters I upstaged Tiger Woods. And I didn’t even pick up a club.”

After 29 months Crane was released. “You walk out and it’s ‘Aaah, freedom,’ ” he says. “Then it’s, ‘Oh s---, what’s next?’ ” He knew that reentering sports broadcasting—at least immediately—was unlikely. He wasn’t prepared, though, for how many other careers would be closed to him. “My first job out of prison was cleaning Porta Potties for minimum wage. I would wear my cap down so people couldn’t see my face. I’m still fresh off being this high-rolling ESPN guy.”

Broke and estranged from much of his family, Crane began, episodically, using again, a violation of his parole that could have put him back in prison. And on June 6, 2013, homeless and isolated, he says he attempted to hang himself in a hotel room. “But as soon as I kicked the chair out [I fell to the floor],” Crane recalls. “I sat there for 12 hours and started writing down things I’d lost: family, career, home. . . . The sixth or seventh thing I wrote—and I kept [that list] in my pocket for a long time—was purpose. I’ve got to find something, a reason. If I’m still here, there’s a reason. And I checked into rehab.”

Ideally, this is where the comeback story begins. But Crane’s last half-decade hasn’t been nearly that tidy or linear; his days make for a ledger filled with wins and losses. He has tried, with varying success, to stay clean. (He says he has been drug-free for five years.) He has tried, with varying success, to reconnect with his two kids and his family. He has tried, with varying success, to restart his career.

One of his wins came in 2015 when he and his son, Cameron, then 17, started a travel baseball team outside Birmingham. Though Crane had never coached, he had the requisite skill set, including bottomless optimism and patience. Crane says his Dizzy Dean League team of 16- and 17-year-olds started out 2–6 . . . and finished 25–10. Soon, enough people wanted to play for Crane that he launched an entire travel program, 31 North, named for the highway that bisects Birmingham. Players came from all over the state, and if they couldn’t afford the entry fees, Crane says, he refused to turn them away. He’d cover them.

In 2018, though, owing to a shortfall of funds, 31 North closed down in the middle of the season, leaving players disappointed and parents irate—and, in at least one instance, demanding a refund. Crane denies a claim that he was found unresponsive in his car during one tournament (he says he had been working three straight days and was exhausted), and he has vowed to form another team for the upcoming season. Still, when he recounts this setback, his voice catches and he clenches a fist in frustration. “Baseball has gotten so expensive,” he says. “It’s becoming a rich-kids sport. I hate seeing kids not get a chance to play.”

As for his own setback, Crane is torn. He cops to his mistakes. No one, he says again and again, told him that robbing a bank was a good idea; no one made him do it. “I was always taught to take your ass-kickings.” At the same time, he feels he has discharged his debt. “If you’re asking me whether I’m ready for life to get easier,” he says, “my answer is yes.”

Crane is now 44. He tends to wear a ballcap over his close-cropped hair, and he still has the compact physique of a former athlete. He has inched back into freelanceing in sports television, reacquainting himself with an EVS. He started working high school football games and has expanded recently to Pro Bull Riders events, pro soccer games for ESPN3, motocross for NBC and college football for CBS Sports Network. He supplements his income by selling sports memorabilia on eBay and says he would like to get into motivational speaking.

Some of his most taxing work has been in repairing relationships that frayed. Crane acknowledges that he has caused a lot of pain for a lot of people, eroded a lot of trust. He says he simply tries to follow the guidance of his probation officer, who has condensed his advice to five words: Do the next right thing.

Anchored as he was in sports media, aware as he was of its capacity for storytelling, Crane knows one of his field’s most durable narratives. One can imagine the highlight package he’d cut: The dazzling talent gets noticed and fulfills—then exceeds—his dreams. He flies high and lives fast, armored with the same unshakable self-belief and sense of invincibility that serves him so well in his day job. Then he makes a spectacular mess of things, suffers, has his moment of reckoning. -Finally, he tries to author a redemptive ending.

And Crane knows this familiar sports arc isn’t limited to athletes.

This story appears in the April 2020 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

Find more Sports Illustrated True Crime stories here

Michael Crane arrived at Augusta a rising star, his video-editing skills sought for every big sporting event on TV. He left in a cop car, high and headed to jail for an audacious robbery.

Michael Crane was no golfer. But he did dream of a star turn at the Masters, a chance to show off his handiwork and skill, a culmination of years of practice. And in April 2007 his chance arrived: At 31 he was handpicked to work one of the most-watched broadcasts on the sports calendar.

A freelance TV editor, Crane specialized in quick-cutting highlight packages that played within event broadcasts—the type that would embroider any big game—and his career was flourishing. That year alone, he recalls having already worked the Super Bowl, the Final Four and more than a dozen other events. Now he would be venturing to the most exalted golf course in the U.S., working for CBS on its commercial-free broadcast of “a tradition unlike any other.”

Yet here it was, the Monday morning of Masters week, and instead of focusing on Augusta National’s greens and, ultimately, the green jacket, Crane was fixated on a different color: red. As in the red dye spurting over his hands and tracing an arc, before splashing onto his rented Chevy Monte Carlo. An exploding cartridge, he would later realize, had been placed in the pile of bills handed to him by a teller at the Augusta bank he had just robbed with two strangers.

Clutching a wad of cash, a look of horror setting in, Crane figured, quite rightly, that he would not be making the final cut at the Masters, after all.

* * *

When Young Michael Crane was asked what he wanted to do when he grew up, reflexively, he would reply: Play in the NFL. Or work for ESPN. His father, an electrician in rural Warrior, Ala., a half hour north of Birmingham, suggested the boy come up with more plausible career choices. The son persisted.

Overcoming a deficit of size (5' 9", 160 pounds) with a surplus of heart, Crane was a running back and an all-state defensive back at Corner High. After one season playing at what is now Western Alabama (in Division II) he quit, in part because of homesickness and in part because he’d married and had a son on the way. His NFL ambitions at an end, he appeared to have abandoned his ESPN aspirations when he took an entry-level job in statement processing at a SouthTrust Bank in Birmingham.

Crane, then 22, spent a few months at that soulless desk job before he got his first break: A friend offered him some freelance work, first shooting, then producing and editing, at a TV startup, College Sports Southeast. He quit his bank job the next week. He’d take any gig in sports TV; if that meant shooting a football game in the rain or getting up in the wee hours to make a kickoff in Kentucky that afternoon—well, what’s 400 miles? “I was making about $18,000,” Crane says, “and I told my wife that if I could get to $30,000, that would be awesome.”

A year or so later, Crane was freelancing at the Great Outdoor Games in Lake Placid, N.Y., when someone asked whether he knew how to operate an EVS machine. “Sure,” he said. Then he asked around: Does anyone know what the hell an EVS is? Crane stayed up all night in his hotel room, reading the manual for a video-editing apparatus that pulls short clips from multiple cameras. By the next day he was at least semiconversant. “It was the ultimate in fake it till you make it,” he says. “I was just hoping I could power up the machine, but it went well.”

Crane didn’t just pick it up quickly; he was a natural, a virtuoso. The equipment—about the size of a laptop, with various dials and levers and buttons—almost came to seem an extension of his arm. Pairing his feel for sports with his dexterity as an editor, he could put together an in-game highlights package in a matter of seconds. If a running back, say, rushed for 100 yards in a half, Crane would pull video from various “looks” and fashion a 20- or 30-second clip of the best runs. “You want the highlights to seem natural, to tell the same story that’s playing out live,” Crane says, “That’s what really good guys who run tape do.”

Pick a big sports moment. Most fans will be able to picture it; they’ll also remember the TV announcer who called it, Al Michaels or Dick Vitale or Joe Buck. The “talent,” though, is only a small part of an ecosystem that is equal parts army and hospital. So-called below-the-line guys—and the vast majority of workers in sports broadcasting remain men—are every bit as responsible for your enjoyment of the game as the folks sitting in hair and makeup. These anonymous operatives in the production truck can make or break a broadcast.

And inside that community word travels fast. Within a year and a half of his introduction to the EVS, Crane’s skills were an open secret. He was a man in demand. “Michael had an innate ability to see things,” says Bob (Rossi) Rosburg, a longtime network sports producer who worked tennis events with Crane in the 2000s, “and, more importantly, to present them in meaningful ways.”

Crane’s dream of working at ESPN? Heck, he’d already worked football and basketball games for the network. Here he was, still in his mid-20s, and John Madden—in the booth for Monday Night Football and in need of quick highlights for his famed telestrator—was asking for him by name. CBS hired him to freelance the NCAA tournament. Golf Channel and Tennis Channel tried to book him the same week. The Grizzlies’ broadcast team enlisted his services, offering him a seat on their plane. In April 2004, Crane worked a tennis tournament for ESPN in Charleston, S.C. Before the week was over a producer asked, “Do you speak French?”

“No,” Crane responded, perplexed. “Why?”

“Because you’re damn good, and we need you in Paris next month to work the French Open.”

Later that summer NBC would send Crane to the Athens Olympics, making for a blistering several weeks of work. “It was nuts,” he recalls. “One minute it would be water polo and the next it would be volleyball.” In part because of his deft handiwork, the network’s coverage at the Games received an Emmy.

Not yet 30, the self-described “Alabama kid” with a hickory-basted drawl was “living the effing life,” he says, making $700 a day before overtime and a per diem, and working 250 days a year. “The only reason it wasn’t more,” he says, “was because I had to turn down jobs.” He was “making national pay,” he notes, “and, remember, I’m living in Alabama.”

The dream came at a price. His marriage fell apart—Crane was in Athens when he asked for a divorce—and all the travel kept him from seeing his son and new daughter as much as he’d like. Still, at his 10th high school reunion he could regale classmates with stories from the road, and he could afford to be quick in throwing down his credit card when his colleagues repaired to the bar at the end of a broadcast.

Like so many of his coworkers, Crane got a rush from the job. If on-air announcers projected calm and authority, the vibe in the truck was the exact opposite, a hive of frenetic energy. It wasn’t simply that live sports are unscripted, unchoreographed, subject to sudden change. It was the knowledge that an audience of millions was about to consume his work.

The stress and the exhilaration, though, were compounded by erratic hours and erratic travel. Crane was working at Wimbledon in 2004 when rain delays threw off his work schedule. By the time the tournament ended he had to fly directly to the Great Outdoor Games in Reno, eight time zones away, and hit the ground running. “Twelve Red Bulls got me through it,” he says. “I was in the truck bouncing off the walls.”

Eventually the natural highs of the job—to say nothing of caffeine-and-taurine-propelled ones—gave way to dark lows. Crane says he did his share of heavy drinking, but cocaine quickly became his drug of choice. He developed a sixth sense for where to find it, sussing out dealers in hotel lobbies, strip clubs and dive bars. More times than he can recall he would show up to work after a sleepless night, still high. “I don’t know,” he says, “if I was hiding [my use] well or not.”

To which coworkers say: yes and no. Brad Douglas, an EVS producer who often worked alongside Crane, including at that 2004 French Open, remembers him showing up late for a shift in Paris, his eyes rimmed in red, two Coca-Colas in one hand and two bags of chips in the other. Douglas recalls thinking, Do what you want in your downtime, but when it affects the broadcasts we’re going to have a problem. And that never happened. “I couldn’t believe what he was doing,” Douglas says. “He could whip together 10 clips and make a highlight package during a commercial break. Audio? Perfect. Timing? On the money. Not one mistake. “You had an uncomfortable feeling that things could go south for him at any moment—but as far as his work, he was a savant.”

* * *

This is what "south" looked like for Michael Crane.

Around 4 p.m. on Sunday, April 1, 2007, he checked into his room at the Augusta Holiday Inn on Gordon Highway, on the west side of town. Then, with half a day to kill before his first production shift, he went about scrounging up a fix. He found a pair of local dealers and invited them back to his room, where he quickly blew through $1,500 on coke and crack. In Crane’s words: It was “an all-night party.”

That party ended the next morning only because he had run out of money. (It might have gone longer, Crane says, had he not let the dealers indulge from their own stash.) Crane didn’t have an ATM card to get more cash. So he made a suggestion that—in his haze, anyway—seemed brilliant: Why not knock off a bank?

In no shape to drive, he gave his dealers the keys to his rental car and jumped in the back seat. The three men headed to a Wachovia branch a few minutes down the highway, six miles from Augusta National. (Three years earlier Wachovia had bought SouthTrust Bank, Crane’s first employer.)

At 9 a.m.—one hour before he was supposed to arrive at work, just as the bank opened—Crane walked through the front door, unarmed and wearing no mask, while the dealers waited in the car. Under his Atlanta Braves visor his face was clearly visible to surveillance cameras. He grabbed a deposit ticket and on the front scribbled a demand for $1,500, claiming to have a gun. Do not say a word. . . . Someone outside as well. . . . Be quick and we leave. Then he presented the note. More confused than scared, the teller asked, “Are you sure you want to do this?”

Crane wasn’t—but he said yes anyway. The teller handed over a stack of bills, inside of which was a packet of distance-activated exploding dye. And just as Crane reached his car, a few hundred feet away from the front exit, the packet exploded. “Holy s---!” came the chorus from the three robbers.

As police cruisers rolled up to the bank, the conspirators sped off, heatedly discussing their next move. When they got back to the Holiday Inn, the dealers split. For Crane, the possibility of missing his shift at the Masters was suddenly the least of his concerns.

The cocaine fog having lifted as the gravity of the situation set in, he figured there was no use in running. He walked to the hotel courtyard, sat on a bench and phoned the Augusta police. When the dispatcher picked up, Crane said words to the effect of: “I know who robbed that Wachovia Bank. He’s staying at the Holiday Inn.”

Crane recalls being overcome by a wicked cocktail of emotions—shame, embarrassment, fear, self-loathing. But perhaps most prominent was relief. He knew he had been out of control for years. “Drugs wear you down, and I was so tired,” he says. “Tired physically, but also tired of screwing up and making bad decisions.”

Lighting a cigarette, he waited for the cops to come arrest him. He confessed to the crime on the spot, took full responsibility over his accomplices and offered to answer any questions. (The two dealers were picked up at the nearby Augusta Super Inn later that day. Their charges were dropped.)

One year earlier, the big scandal from Augusta before play started had been about a 26-year-old man who fired a gun at the courtesy car assigned to golfer Tom Lehman. The guy from the broadcast team who tried to jack a local bank was a whole new level of outré pretournament news. While word of Crane’s arrest—and the bizarre circumstances—rocketed around the television compound, he was booked at Richmond County Jail on a robbery charge.

Then he made one last error: He declared himself a suicide risk, hoping he would be put in a cell by himself. The intake officer took all of Crane’s personal possessions, including his clothes, and assigned him to a room with six other men who were also deemed dangers to themselves.

Crane had expected to spend the week at perhaps the most pristine and dignified enclave in sports. Instead, as Zach Johnson was being feted on Sunday and fitted with a green jacket, Crane was 13 miles away, sharing, he says, a cell with a half-dozen other naked accused felons.

* * *

After pleading guilty that October to bank robbery by force and intimidation, Crane was sentenced to 37 months—the recommended minimum—at a federal correction facility in Talladega. He was despondent about his plight until a cellmate summoned him. “He says, ‘Michael, get in here. I want to show you something. Bring your paperwork,’ ” Crane recalls. “He goes, ‘See your release date? . . . Let me show you mine.’ He pulls it out. It says: death. After that I stopped moping.”

Sports also helped Crane get through what “seemed like an eternity” in prison. He could hold his own on a softball field and on a basketball court, but his line of work gave him real currency among the inmates. He could rattle off stories from the Super Bowls he’d worked and the times he’d flown on an NBA team’s charter. Eventually, he could also joke about the felonious misadventure in Augusta. His go-to setup line before launching into an account of his saga: “One year at the Masters I upstaged Tiger Woods. And I didn’t even pick up a club.”

After 29 months Crane was released. “You walk out and it’s ‘Aaah, freedom,’ ” he says. “Then it’s, ‘Oh s---, what’s next?’ ” He knew that reentering sports broadcasting—at least immediately—was unlikely. He wasn’t prepared, though, for how many other careers would be closed to him. “My first job out of prison was cleaning Porta Potties for minimum wage. I would wear my cap down so people couldn’t see my face. I’m still fresh off being this high-rolling ESPN guy.”

Broke and estranged from much of his family, Crane began, episodically, using again, a violation of his parole that could have put him back in prison. And on June 6, 2013, homeless and isolated, he says he attempted to hang himself in a hotel room. “But as soon as I kicked the chair out [I fell to the floor],” Crane recalls. “I sat there for 12 hours and started writing down things I’d lost: family, career, home. . . . The sixth or seventh thing I wrote—and I kept [that list] in my pocket for a long time—was purpose. I’ve got to find something, a reason. If I’m still here, there’s a reason. And I checked into rehab.”

Ideally, this is where the comeback story begins. But Crane’s last half-decade hasn’t been nearly that tidy or linear; his days make for a ledger filled with wins and losses. He has tried, with varying success, to stay clean. (He says he has been drug-free for five years.) He has tried, with varying success, to reconnect with his two kids and his family. He has tried, with varying success, to restart his career.

One of his wins came in 2015 when he and his son, Cameron, then 17, started a travel baseball team outside Birmingham. Though Crane had never coached, he had the requisite skill set, including bottomless optimism and patience. Crane says his Dizzy Dean League team of 16- and 17-year-olds started out 2–6 . . . and finished 25–10. Soon, enough people wanted to play for Crane that he launched an entire travel program, 31 North, named for the highway that bisects Birmingham. Players came from all over the state, and if they couldn’t afford the entry fees, Crane says, he refused to turn them away. He’d cover them.

In 2018, though, owing to a shortfall of funds, 31 North closed down in the middle of the season, leaving players disappointed and parents irate—and, in at least one instance, demanding a refund. Crane denies a claim that he was found unresponsive in his car during one tournament (he says he had been working three straight days and was exhausted), and he has vowed to form another team for the upcoming season. Still, when he recounts this setback, his voice catches and he clenches a fist in frustration. “Baseball has gotten so expensive,” he says. “It’s becoming a rich-kids sport. I hate seeing kids not get a chance to play.”

As for his own setback, Crane is torn. He cops to his mistakes. No one, he says again and again, told him that robbing a bank was a good idea; no one made him do it. “I was always taught to take your ass-kickings.” At the same time, he feels he has discharged his debt. “If you’re asking me whether I’m ready for life to get easier,” he says, “my answer is yes.”

Crane is now 44. He tends to wear a ballcap over his close-cropped hair, and he still has the compact physique of a former athlete. He has inched back into freelanceing in sports television, reacquainting himself with an EVS. He started working high school football games and has expanded recently to Pro Bull Riders events, pro soccer games for ESPN3, motocross for NBC and college football for CBS Sports Network. He supplements his income by selling sports memorabilia on eBay and says he would like to get into motivational speaking.

Some of his most taxing work has been in repairing relationships that frayed. Crane acknowledges that he has caused a lot of pain for a lot of people, eroded a lot of trust. He says he simply tries to follow the guidance of his probation officer, who has condensed his advice to five words: Do the next right thing.

Anchored as he was in sports media, aware as he was of its capacity for storytelling, Crane knows one of his field’s most durable narratives. One can imagine the highlight package he’d cut: The dazzling talent gets noticed and fulfills—then exceeds—his dreams. He flies high and lives fast, armored with the same unshakable self-belief and sense of invincibility that serves him so well in his day job. Then he makes a spectacular mess of things, suffers, has his moment of reckoning. -Finally, he tries to author a redemptive ending.

And Crane knows this familiar sports arc isn’t limited to athletes.

This story appears in the April 2020 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

Find more Sports Illustrated True Crime stories here

0 Comments