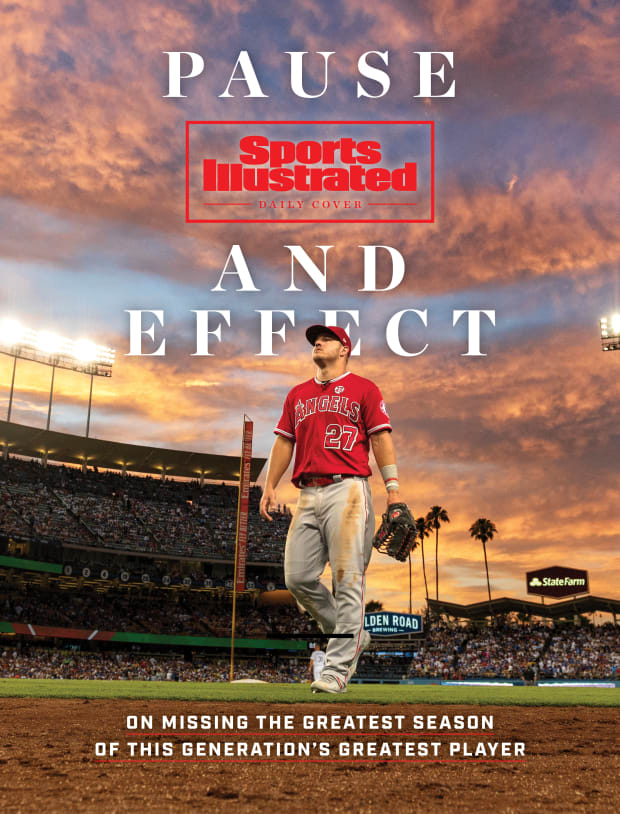

This season, more so than any other, promised to be Mike Trout's best yet.

Every baseball season at its start is a blue Tiffany box tied with white satin ribbon in the palm of your hand. Something special will be revealed, guaranteed. The mysteries are in only the particulars and magnitude of its bejeweled splendor.

We could have made one easy guess about this season. It promised to be the greatest season of the greatest player of this generation, Mike Trout.

Instead, the coronavirus pandemic has stolen the probability of such a gift—the gift of one full season of peak Trout. It is one of

a million small consequences that today mean nothing against the global threat to human life. But within the baseball community it is a consequence that will have aesthetic and historical import.

Trout turns 29 on Aug. 7. The Angels' center fielder is coming off a season in which he set career highs for home runs (45) and slugging (.645), even though he missed the final three weeks of the season with a foot injury that had been bothering him for at least the month prior. He has missed an average of 33 games per year over the past three seasons. He likely will miss many more than that this year, making it four straight years in the prime of his career that Trout will not play more than 140 games. If we see Major League Baseball again this summer, we should be surprised and grateful.

Because Trout was so good so young, he is at the golden nexus of an athlete’s life when accumulated wisdom (from 1,199 career games and 22,652 pitches seen) intersects with physical peak. Enhancing such synchronicity are the addition to the Angels lineup of third baseman Anthony Rendon and the return to health of DH Shohei Ohtani, left fielder Justin Upton and second baseman Tommy La Stella. Trout never has been better and never had a better lineup around him, and yet now he never will play until the day when our public health is not threatened, a day so far off it is only an imagined one right now.

“Last year they were pitching me a lot more inside and I had to pull the ball more,” Trout tells me before spring training camps shut down. “Early in my career I was more right-center power, and then they started pitching me different and I had to make adjustments.

“Obviously in high school and throughout my early years I pulled the ball. And then I learned how to hit the ball the other way and that really helped me. But like I said, when they’re pitching you inside you have to make adjustments.”

Trout will never get these games back. We all age, but there is an added cruelty to the aging of an athlete because of the rapid decline in the skills that make them valuable. A 2007 study by a University of Colorado research team found that one out of every five players who reaches the majors never plays a second season. They found the average major league career is 5.6 years.

The researchers wrote, “Whereas a normal work career typically involves a gradual ascent followed by a slow decline, baseball careers are characterized by rapid ascent followed by rapid decline, or more accurately as an inevitably short time on a very slippery slope.”

Here is a reminder of the slipperiness of that slope: Just four years ago, in 2016, Mark Trumbo led the majors in home runs. Trumbo, Khris Davis, Brian Dozier, Chris Carter and Todd Frazier were five of the seven players to hit 40 homers. All are in various stages of decline.

A truncated season of prime Trout will forever leave a bittersweet “what if?” aftertaste to his career, no matter how great his legacy. This is what war, labor stoppages, injuries and pandemics wreak on the slippery slope of a career.

It happened more than 100 years ago to Washington outfielder Sam Rice at the same age. After finishing fifth in hits in the American League in 1917, Rice was summoned by the U.S. Army just as the 1918 season began and as World War I raged.

Based on his hitting prowess, Rice lost 146 hits in his age-28 season that year. He finished his career with 2,987 hits, holding a record that still stands today for the most hits without reaching 3,000.

Also, the 1981 strike interrupted what was the greatest slugging season in the career of Mike Schmidt, then 31 (.644). He lost 15 homers. He retired with 548.

The strike in 1994–95 cost Fred McGriff, then 30, 18 home runs. He finished with 493 homers, leaving him short not just of 500 but also of the late-career appreciation, the halo effect that comes with it and enough support for the Hall of Fame.

That same strike cost Ken Griffey Jr. a run at breaking Roger Maris’s record of 61 home runs. At 24, Griffey had 40 homers—on pace for 58—and a .674 slugging percentage when the strike hit. He never slugged that high before or after.

No greater “what if?” applies than the one to the career of Ted Williams. The Red Sox slugger lost his age-24, -25 and -26 seasons to serve in World War II and missed all but 43 games in his age-33 and -34 seasons to serve in the Korean War. Williams lost about 154 homers, finishing with 521 instead of 675.

What will Trout lose? Probably his best chance to make a run at 60 home runs. Before his foot injury, Trout was on pace through 128 games last year to hit 53 homers. As hitters age they tend to lose points off their batting average (as well as running speed) but gain power—for a while, anyway. Trout once stole 49 bases to lead the league. His running days essentially are over. Last year he attempted only 13 stolen bases, half of what he tried the previous season. He hit .291, the second lowest of his eight full seasons.

At 28, Trout is becoming more of a slugger, following not only the general arc in the game but the traditional aging curve of great players across eras. To get an idea of whether this season would have been Trout at the best we will ever see him, we should define what makes a player’s peak. But rather than compare Trout with the general player population–in which 20% of players are one-and-done–let’s compare him with the 10 players he most resembles statistically at this age and when they hit their peak. We’ll use three ways to measure peak: career highs in home runs, batting average and wins above replacement.

Age at Career Peak

You can see the power/average trade-off, as players hit their power peak about three years after their batting average peak. You also see the narrow window when they reach peak WAR. Trout is unlikely to the match the .326 he reached as a rookie. (Apologies for bringing up batting average, but for a century that’s the number hitters chased, giving it historical significance if not modern relevance.)

Overall, of the 33 peak measurements above, only nine were reached at the age Trout is this season and, with no peaks likely this season, just seven at his age next season, when he turns 30. Like Aaron, Trout would have to be an outlier among outliers to think his best is still to come.

Well, he is Mike Trout, so that’s possible. What I find most impressive about Trout is despite having reached a high ceiling at such a young age, he improves his game constantly. He was knocked for having a weak throwing arm, but improved that to above-average. He was knocked for an inability to hit high fastballs, but conquered those. He was knocked for conceding too many strikes early in counts, but learned to ambush pitchers on first pitches. He was knocked for too many strikeouts (he led the league with 184 in 2014), but over the past three seasons has almost as many walks (326) as strikeouts (334).

But when I asked Trout to identify his greatest strength, his answer surprised me.

“My greatest strength is … I’m saying awareness,” he says. “I try to visualize stuff before it happens, and my instincts just take over.”

It might be the most self-revealing statement I’ve heard from Trout. This is where that wisdom from playing 1,199 games and seeing 22,652 pitches come in. Trout is not a scientific or theoretical hitter. He is a pragmatist. What he calls “my instincts” is the enormous well of trust he has in his ability to play baseball.

A cynic might suggest it’s easy to harbor such trust when you’re as good as Mike Trout. But with Trout one doesn’t follow the other; they braid like two strands of rope, each made stronger concurrently by the other. Trout plays joyfully and without fear of outcome. It is fiercely liberating. If there are pictures of Trout angry or down on a baseball field because of a poor outcome, I don’t remember seeing them.

We can see the pragmatist in Trout when we delve into his increase in power last year. I mentioned to Trout how he hit more balls in the air last season. As recently as 2016 he hit more grounders than fly balls. Last year he hit a career-low percentage of ground balls. When I asked him why, his response was classic Trout: “Not by design. I couldn’t tell you.”

We also saw his pragmatism in his response to how pitchers worked him. It’s not much more complicated to him than “they pitched me more inside, so I pulled it more.” Yeah, he’s that good.

As Trout ages, he is becoming a bigger home run threat because he has broadened what was his baseline approach of staying inside the baseball to rip line drives over the second baseman’s head to split the center fielder and right fielder. He is turning on more pitches—there’s that wisdom of seeing 22,652 pitches.

Trout never was more dangerous pulling the ball than he was last year. Check out his improvement to the pull side:

Trout's Power to Pull Side

*Minimum 50 results

Trout pulled more home runs last year (28) than in his two previous MVP years combined (25). Why? In this case his “instincts” are wrong. It’s not because pitchers are throwing inside more to him. The past two seasons mark the fewest inside pitches Trout has seen in his career. (Inside is defined as from the inner third of the plate to the body.)

Why then has Trout become such a pull-side monster? He is catching fastballs out in front of the plate—no matter where they are located—just a click earlier than when he first came up, when he established himself as an inside-out hitter. Last year Trout pulled 18 fastballs for home runs—after never having hit more than 10 like that in a season. Eleven of those 18 fastballs were middle-to-away, not in.

It’s not that he’s selling out. He knows how the game has changed just in his nine years in the big leagues (home runs, not singles, win games) and knows when to pick his spots to ambush.

He also has sharpened his incredible plate discipline. Of the 45 homers Trout hit last season, 44 were hit on pitches in the strike zone. (The exception was his first home run, a 422-foot blast on a 3-and-1 changeup from Edinson Vólquez that was down.) He is superb at forcing pitchers into the strike zone.

Trout has led the league in steals, runs, RBI, walks, total bases, on-base and slugging but has never won a home run title. He has hit 285 career home runs and, if the schedule allows, will become only the second player ever with 300 homers and 200 stolen bases before turning 29, joining Álex Rodríguez, who did so on steroids. When I mentioned to Trout the upcoming likelihood of reaching 300 homers, he had no idea about it—nor was he that close to knowing his career total.

“I didn’t even really know that until you just told me,” he says. “I think it’s 260 or 270 or something. I probably won’t think about it until I get to 299, and then I’ll try to hit 300 when I shouldn’t. If I go up there trying to hit a home run, I’m probably going to make an out.

“But I don’t think about numbers. But I like watching it. I like watching Albert [Pujols] pass Babe Ruth or something. I see that. But individual statistics? Not really.”

This is the most startling statistic about Trout: He never has won a postseason game. Rare is the elite player who has been shut out like this, especially in an era of expanded playoffs. Look at it this way: Among the 10 players with the most total bases through their age-27 season, Trout is the only one never to have won a playoff game.

Most Total Bases Through Age-27 Season

“Goals?” Trout says in repeating part of the question I asked him. “Just get to the playoffs. I know that’s the biggest thing people are saying about my career so far–not playing in the postseason. This offseason was a good way to start, adding Rendon and some guys who are going to help us get there.”

I asked him whether he considered this Angels team to be the best of his 10 Angels teams.

“Offensively, for sure,” he says. “When I first came up, we had a lot of great arms, veteran guys who had established themselves. We have a lot of great arms now, obviously with [Andrew] Heaney and we brought in some guys who made big impact over the years, and we have young guys trying to prove themselves.”

Now the promise of his team and of his prime are on hold. The box is left unopened. We know not when baseball will resume. Games and moments are lost for good. With Trout, we can only imagine the greatness we are missing.

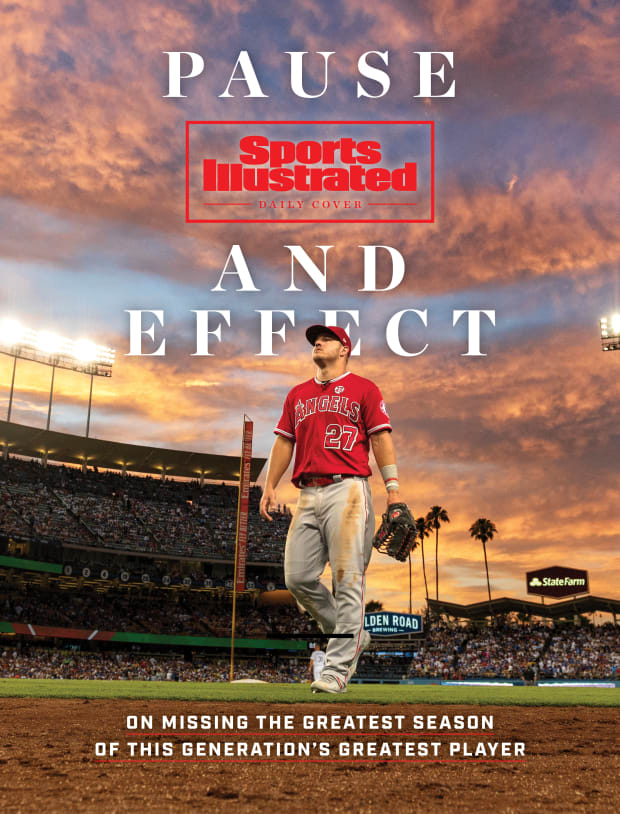

This season, more so than any other, promised to be Mike Trout's best yet.

Every baseball season at its start is a blue Tiffany box tied with white satin ribbon in the palm of your hand. Something special will be revealed, guaranteed. The mysteries are in only the particulars and magnitude of its bejeweled splendor.

We could have made one easy guess about this season. It promised to be the greatest season of the greatest player of this generation, Mike Trout.

Instead, the coronavirus pandemic has stolen the probability of such a gift—the gift of one full season of peak Trout. It is one of a million small consequences that today mean nothing against the global threat to human life. But within the baseball community it is a consequence that will have aesthetic and historical import.

Trout turns 29 on Aug. 7. The Angels' center fielder is coming off a season in which he set career highs for home runs (45) and slugging (.645), even though he missed the final three weeks of the season with a foot injury that had been bothering him for at least the month prior. He has missed an average of 33 games per year over the past three seasons. He likely will miss many more than that this year, making it four straight years in the prime of his career that Trout will not play more than 140 games. If we see Major League Baseball again this summer, we should be surprised and grateful.

Because Trout was so good so young, he is at the golden nexus of an athlete’s life when accumulated wisdom (from 1,199 career games and 22,652 pitches seen) intersects with physical peak. Enhancing such synchronicity are the addition to the Angels lineup of third baseman Anthony Rendon and the return to health of DH Shohei Ohtani, left fielder Justin Upton and second baseman Tommy La Stella. Trout never has been better and never had a better lineup around him, and yet now he never will play until the day when our public health is not threatened, a day so far off it is only an imagined one right now.

“Last year they were pitching me a lot more inside and I had to pull the ball more,” Trout tells me before spring training camps shut down. “Early in my career I was more right-center power, and then they started pitching me different and I had to make adjustments.

“Obviously in high school and throughout my early years I pulled the ball. And then I learned how to hit the ball the other way and that really helped me. But like I said, when they’re pitching you inside you have to make adjustments.”

Trout will never get these games back. We all age, but there is an added cruelty to the aging of an athlete because of the rapid decline in the skills that make them valuable. A 2007 study by a University of Colorado research team found that one out of every five players who reaches the majors never plays a second season. They found the average major league career is 5.6 years.

The researchers wrote, “Whereas a normal work career typically involves a gradual ascent followed by a slow decline, baseball careers are characterized by rapid ascent followed by rapid decline, or more accurately as an inevitably short time on a very slippery slope.”

Here is a reminder of the slipperiness of that slope: Just four years ago, in 2016, Mark Trumbo led the majors in home runs. Trumbo, Khris Davis, Brian Dozier, Chris Carter and Todd Frazier were five of the seven players to hit 40 homers. All are in various stages of decline.

A truncated season of prime Trout will forever leave a bittersweet “what if?” aftertaste to his career, no matter how great his legacy. This is what war, labor stoppages, injuries and pandemics wreak on the slippery slope of a career.

It happened more than 100 years ago to Washington outfielder Sam Rice at the same age. After finishing fifth in hits in the American League in 1917, Rice was summoned by the U.S. Army just as the 1918 season began and as World War I raged.

Based on his hitting prowess, Rice lost 146 hits in his age-28 season that year. He finished his career with 2,987 hits, holding a record that still stands today for the most hits without reaching 3,000.

Also, the 1981 strike interrupted what was the greatest slugging season in the career of Mike Schmidt, then 31 (.644). He lost 15 homers. He retired with 548.

The strike in 1994–95 cost Fred McGriff, then 30, 18 home runs. He finished with 493 homers, leaving him short not just of 500 but also of the late-career appreciation, the halo effect that comes with it and enough support for the Hall of Fame.

That same strike cost Ken Griffey Jr. a run at breaking Roger Maris’s record of 61 home runs. At 24, Griffey had 40 homers—on pace for 58—and a .674 slugging percentage when the strike hit. He never slugged that high before or after.

No greater “what if?” applies than the one to the career of Ted Williams. The Red Sox slugger lost his age-24, -25 and -26 seasons to serve in World War II and missed all but 43 games in his age-33 and -34 seasons to serve in the Korean War. Williams lost about 154 homers, finishing with 521 instead of 675.

What will Trout lose? Probably his best chance to make a run at 60 home runs. Before his foot injury, Trout was on pace through 128 games last year to hit 53 homers. As hitters age they tend to lose points off their batting average (as well as running speed) but gain power—for a while, anyway. Trout once stole 49 bases to lead the league. His running days essentially are over. Last year he attempted only 13 stolen bases, half of what he tried the previous season. He hit .291, the second lowest of his eight full seasons.

At 28, Trout is becoming more of a slugger, following not only the general arc in the game but the traditional aging curve of great players across eras. To get an idea of whether this season would have been Trout at the best we will ever see him, we should define what makes a player’s peak. But rather than compare Trout with the general player population–in which 20% of players are one-and-done–let’s compare him with the 10 players he most resembles statistically at this age and when they hit their peak. We’ll use three ways to measure peak: career highs in home runs, batting average and wins above replacement.

Age at Career Peak

You can see the power/average trade-off, as players hit their power peak about three years after their batting average peak. You also see the narrow window when they reach peak WAR. Trout is unlikely to the match the .326 he reached as a rookie. (Apologies for bringing up batting average, but for a century that’s the number hitters chased, giving it historical significance if not modern relevance.)

Overall, of the 33 peak measurements above, only nine were reached at the age Trout is this season and, with no peaks likely this season, just seven at his age next season, when he turns 30. Like Aaron, Trout would have to be an outlier among outliers to think his best is still to come.

Well, he is Mike Trout, so that’s possible. What I find most impressive about Trout is despite having reached a high ceiling at such a young age, he improves his game constantly. He was knocked for having a weak throwing arm, but improved that to above-average. He was knocked for an inability to hit high fastballs, but conquered those. He was knocked for conceding too many strikes early in counts, but learned to ambush pitchers on first pitches. He was knocked for too many strikeouts (he led the league with 184 in 2014), but over the past three seasons has almost as many walks (326) as strikeouts (334).

But when I asked Trout to identify his greatest strength, his answer surprised me.

“My greatest strength is … I’m saying awareness,” he says. “I try to visualize stuff before it happens, and my instincts just take over.”

It might be the most self-revealing statement I’ve heard from Trout. This is where that wisdom from playing 1,199 games and seeing 22,652 pitches come in. Trout is not a scientific or theoretical hitter. He is a pragmatist. What he calls “my instincts” is the enormous well of trust he has in his ability to play baseball.

A cynic might suggest it’s easy to harbor such trust when you’re as good as Mike Trout. But with Trout one doesn’t follow the other; they braid like two strands of rope, each made stronger concurrently by the other. Trout plays joyfully and without fear of outcome. It is fiercely liberating. If there are pictures of Trout angry or down on a baseball field because of a poor outcome, I don’t remember seeing them.

We can see the pragmatist in Trout when we delve into his increase in power last year. I mentioned to Trout how he hit more balls in the air last season. As recently as 2016 he hit more grounders than fly balls. Last year he hit a career-low percentage of ground balls. When I asked him why, his response was classic Trout: “Not by design. I couldn’t tell you.”

We also saw his pragmatism in his response to how pitchers worked him. It’s not much more complicated to him than “they pitched me more inside, so I pulled it more.” Yeah, he’s that good.

As Trout ages, he is becoming a bigger home run threat because he has broadened what was his baseline approach of staying inside the baseball to rip line drives over the second baseman’s head to split the center fielder and right fielder. He is turning on more pitches—there’s that wisdom of seeing 22,652 pitches.

Trout never was more dangerous pulling the ball than he was last year. Check out his improvement to the pull side:

Trout's Power to Pull Side

*Minimum 50 results

Trout pulled more home runs last year (28) than in his two previous MVP years combined (25). Why? In this case his “instincts” are wrong. It’s not because pitchers are throwing inside more to him. The past two seasons mark the fewest inside pitches Trout has seen in his career. (Inside is defined as from the inner third of the plate to the body.)

Why then has Trout become such a pull-side monster? He is catching fastballs out in front of the plate—no matter where they are located—just a click earlier than when he first came up, when he established himself as an inside-out hitter. Last year Trout pulled 18 fastballs for home runs—after never having hit more than 10 like that in a season. Eleven of those 18 fastballs were middle-to-away, not in.

It’s not that he’s selling out. He knows how the game has changed just in his nine years in the big leagues (home runs, not singles, win games) and knows when to pick his spots to ambush.

He also has sharpened his incredible plate discipline. Of the 45 homers Trout hit last season, 44 were hit on pitches in the strike zone. (The exception was his first home run, a 422-foot blast on a 3-and-1 changeup from Edinson Vólquez that was down.) He is superb at forcing pitchers into the strike zone.

Trout has led the league in steals, runs, RBI, walks, total bases, on-base and slugging but has never won a home run title. He has hit 285 career home runs and, if the schedule allows, will become only the second player ever with 300 homers and 200 stolen bases before turning 29, joining Álex Rodríguez, who did so on steroids. When I mentioned to Trout the upcoming likelihood of reaching 300 homers, he had no idea about it—nor was he that close to knowing his career total.

“I didn’t even really know that until you just told me,” he says. “I think it’s 260 or 270 or something. I probably won’t think about it until I get to 299, and then I’ll try to hit 300 when I shouldn’t. If I go up there trying to hit a home run, I’m probably going to make an out.

“But I don’t think about numbers. But I like watching it. I like watching Albert [Pujols] pass Babe Ruth or something. I see that. But individual statistics? Not really.”

This is the most startling statistic about Trout: He never has won a postseason game. Rare is the elite player who has been shut out like this, especially in an era of expanded playoffs. Look at it this way: Among the 10 players with the most total bases through their age-27 season, Trout is the only one never to have won a playoff game.

Most Total Bases Through Age-27 Season

“Goals?” Trout says in repeating part of the question I asked him. “Just get to the playoffs. I know that’s the biggest thing people are saying about my career so far–not playing in the postseason. This offseason was a good way to start, adding Rendon and some guys who are going to help us get there.”

I asked him whether he considered this Angels team to be the best of his 10 Angels teams.

“Offensively, for sure,” he says. “When I first came up, we had a lot of great arms, veteran guys who had established themselves. We have a lot of great arms now, obviously with [Andrew] Heaney and we brought in some guys who made big impact over the years, and we have young guys trying to prove themselves.”

Now the promise of his team and of his prime are on hold. The box is left unopened. We know not when baseball will resume. Games and moments are lost for good. With Trout, we can only imagine the greatness we are missing.

0 Comments