What did the Bundesliga's return really look like, and how was it able to happen? From the atypical bus ride to a derby to the meticulous hotel and stadium protocol, take a detailed view of what's gone into bringing the German league back.

In seasons past, you didn’t need to hear the din coming from the Westfalenstadion’s towering south stand, which can hold 25,000, to get the pulse racing on derby day. The buzz began well in advance, during the 20-mile drive between Gelsenkirchen and Dortmund. They’re smaller cities on a national scale, but they’re at the heart of western Germany’s bustling, congested and soccer-mad Ruhr region. And they’re at opposite ends of the Bundesliga’s most heated rivalry—the Revierderby between Schalke 04 and Borussia Dortmund.

“Normally on a Saturday morning on the Autobahn, you can see fans traveling from one city to the other. Especially in western Germany. You see fans with every color, and there’s a lot of traffic in front of the stadium,” said Jochen Schneider, Schalke’s director of sport.

Said Schalke’s American midfielder, Weston McKennie, “Whenever you are driving to that game, you see police escorts and a bunch of fans on the road. You see fans when you get there. You have Dortmund fans throwing fingers at you, and maybe occasionally, if they really have the balls, they’ll throw a beer at the bus.”

The

rivals met again last Saturday, in the 156th competitive Revierderby and also the first of its kind. Dortmund’s south stand—the Yellow Wall—was empty. And so were the Autobahn 40 and the rest of the roads. The bottlenecks, spiteful gestures and projectiles were absent.“It was totally different. There was nobody on the street,” Schneider said.

Added McKennie: “There was no need for a police escort or security. It was pretty quiet. The fans definitely are a big part of that game. Driving there, you see your fans and their fans, seeing them go at it with each other at times. It definitely riles you up for the game and gets you excited even more than usual. It was a big factor that was missing.”

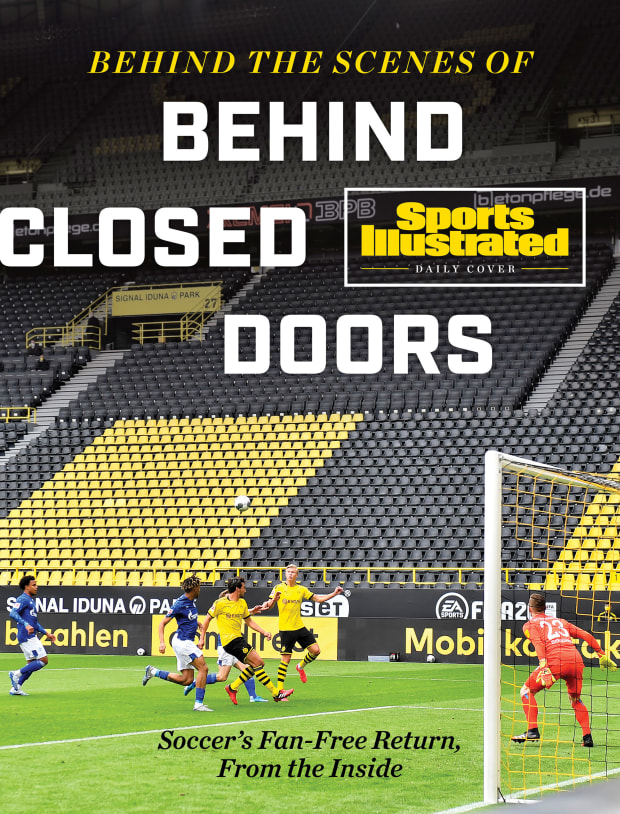

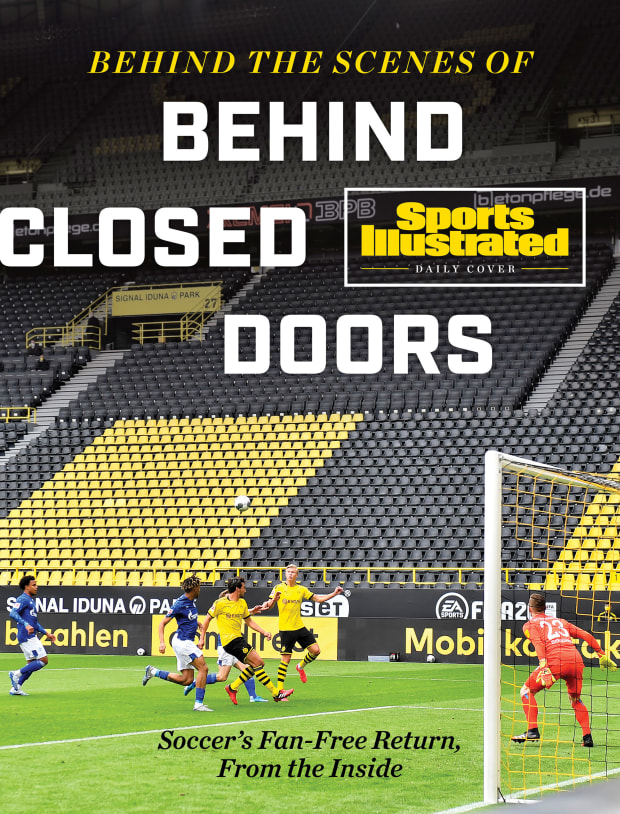

And it would get only stranger from there. Saturday’s Revierderby was what the Germans call a “Geisterspiel”—a “ghost game.” It was soccer without any of the traditional sound and fury that help make it the most popular sport in the world. There were 22 men on the Westfalenstadion field, plus officials. There were 90 minutes of play, with shots and goals and all the technical trappings of the game. But the atmosphere—the communal aspect of match day so crucial to Germans’ consumption of the sport—was missing. There was no player procession, and no pregame photo or captains’ handshake. The stands were barren and banner-free, the only sound in the 81,365-seat arena coming from shouting players and the occasional ‘thwack’ of the ball against the post or rigging.

The surroundings were so surreal that Dortmund manager Lucien Favre asked a sport psychologist to help prepare his players during the days preceding the game. It may have helped. His side won emphatically, 4–0.

But that relative silence and those empty seats were ironic reminders of how much scrutiny was focused on the Revierderby and the rest of last weekend’s Bundesliga slate. These Geisterspiels represented a massive, albeit abnormal step toward a long-awaited return to normalcy, and they were being watched around the world. The Bundesliga and its second tier, the 2. Bundesliga, were the first leagues of global import to return to action following a break necessitated by the coronavirus pandemic (the Bundesliga is the second-best attended professional league on the planet behind the NFL), and they were doing so well before other major circuits in Europe and the USA.

The Bundesliga’s complex return-to-play plan and the Geisterspiels would serve either as a road map for others, or as a warning; as an homage to discipline, cooperation and the power of protocol, or as a symbol of hubris and greed. The final scores were far from the only results being followed.

“We wanted to play and finish up the season and get it over with, and we were willing to sacrifice what we needed to make that happen,” McKennie told Sports Illustrated. “I think there’s a feeling here like, everyone’s going to follow your pathway and how we did it, and how we were able to minimize [the virus] and continue on with everyday life.”

McKennie, an FC Dallas product, is one of several noteworthy members of a refreshed U.S. national team player pool now working in Germany, making the Bundesliga a league of significant interest for U.S. fans. Dortmund, which developed Christian Pulisic (now at Chelsea), features Gio Reyna, the 17-year-old son of U.S. legend Claudio Reyna who would’ve started the Revierderby if not for an injury suffered while warming up. Midfielder Tyler Adams (RB Leipzig), injured goalkeeper Zack Steffen (Fortuna Düsseldorf), striker Josh Sargent (Werder Bremen) and center back John Brooks (Wolfsburg) are among the other Bundesliga-based players likely to feature in the build-up to the 2022 World Cup.

German soccer’s open-minded outlook on American players—they’re relatively cheap compared to counterparts from more traditional powers—is emblematic of its analytical approach to so many facets of the game, from player development and marketing to this month’s return to the field. Last weekend’s matches were a triumph of organization and procedure, led by Deutsche Fussball Liga (DFL) executives who started working within days of the March shutdown, and backed by a government headed by a chancellor, Angela Merkel, who happens to hold a doctorate degree in quantum chemistry.

“That we’re allowed to play again boils down to German politics for managing this crisis, and the health system in Germany,” DFL CEO Christian Seifert told reporters. “If I were to name the number of tests that I was asked about in teleconferences with other professional leagues, with American professional leagues, with clubs from the NFL, the NHL, Major League Baseball and others, and I tell them how many tests are possible in Germany, they generally check, or there’s silence, because it’s just unimaginable in the situation over there.”

While U.S. sports officials ponder sending every team to Orlando or Las Vegas, while athletes there still haven’t returned to formal training, and while the government spins its wheels and debates the healing power of bleach, the situation isn’t dramatically better in Europe. The soccer leagues in France, Netherlands, Belgium and Scotland already have canceled the remainder of their 2019–20 seasons. England’s Premier League, Spain’s La Liga and Italy’s Serie A now are targeting a mid-June kickoff. Meanwhile, the Bundesliga hopes to have its season finished—each team has eight games remaining—by the end of next month.

From the start, Germany weathered the pandemic better than its peers. According to the World Health Organization, it has suffered some 8,100 coronavirus deaths. The countries that host Europe’s other “big” soccer leagues—France, Italy, Spain and the U.K.—have each endured more than three times that figure. German society has been gradually reopening since late April. But that doesn’t mean the public was firmly behind the Bundesliga’s restart. Some felt it signaled misplaced priorities, while others were offended by the Geisterspiel idea.

“The overall opinion in Germany was not that positive,” Schneider said. “People are fighting for their jobs. Kids cannot go to school. Why on earth should the football players be allowed to play their games again? We needed a strong concept to convince the politicians.”

A lot was riding on that concept and then last weekend’s implementation. The Bundesliga is popular and relatively wealthy, but its individual members aren’t necessarily among sports’ most valuable or profitable franchises. On Forbes’ most recent list of the world’s 50 most valuable teams, only seven-time defending champion Bayern Munich (No. 17) warranted a place. And according to the Deloitte's 2020 Football Money League report, only Bayern (No. 4), Dortmund (No. 12) and Schalke (No. 15) are among soccer’s top 25 revenue-producing clubs. The Bundesliga is broadcast in more than 200 countries, but it can’t compete with England’s Premier League on rights fees, and only Bayern has anything close to the global cachet enjoyed by the likes of Barcelona and Real Madrid. Further, German teams are subject to a rule requiring a majority of each club to be owned by its members, limiting the influence a super-wealthy oligarch or government can have over its finances.

In other words, despite the Bundesliga’s size and popularity, returning to the field sooner rather than later was a matter of economic survival. Seifert said canceling the remainder of the season would cost some $800 million.

“Every football club, not only Schalke, survives on TV revenue. Without being able to finish the season, many professional football clubs would have been in big trouble from a financial stability side,” Schalke director of marketing and communications Alexander Jobst said. “Schalke is an independent football club. We belong to our members. We don’t have foreign investors, so we belong even more to our TV revenue and sponsorship and ticket revenue. If this disappears, we don’t have an investor who pumps in millions of Euros to survive.”

Jobst estimated that a third of Schalke’s revenue comes from TV, a third from sponsorship (which is tied to TV), and a third from ticketing and match day. Playing in an empty stadium eliminates the latter, which at Schalke’s Veltins-Arena comes to around $2.2 million per game. Fans who haven’t asked for their season-ticket money back get a shirt featuring the emblem of the club’s “Only Together” coronavirus campaign.

So a TV product was created. The DFL huddled with health authorities, municipalities, its TV partners and clubs to create an exhaustive return-to-play plan—the English version is 50 pages long—that was approved by the German government on May 6. It involved a lot of people, many moving parts and would require significant discipline, especially from the players. They would be tested at least twice a week (the DFL is paying for around 20,000 tests, which Seifert said would compose no more than 0.4% of Germany’s capacity), and would have to be quarantined for a week preceding the first game. Afterward, the plan forbids contact with neighbors or visitors and the use of public transportation, among other activities.

“We told them, you have to create two quarantine situations, one at home and the other here at the training ground. We have to avoid as much as possible any contact with other people,” Schneider said.

The club went so far as to do grocery shopping for players who were unable or reluctant to do so. Their items were waiting for them at Schalke’s facility following practice. Jobst said there even were opportunities for club sponsors, who were searching for ways to be involved during the shutdown, to help feed and support the players.

“Schalke in general has been doing a really good job, even though sometimes there might be a feeling of, ‘Do we really have to do this?’ But at the same time, you’re thankful for it because it’s really going to protect you,” McKennie said.

“The Germans are very disciplined,” he continued. “When they have something they want to do or they have a system they need to put in place, or certain rules, they’re really strict about them and most people here will follow the rules as much as they can. That’s just kind of how Germans are and how they’re brought up.”

Jobst and Schneider said that worried players were given the opportunity to back out of the return to play without repercussion, but all were willing to comply. They entered quarantine at the beginning of last week inside a Courtyard Marriott located just a block north of Schalke’s stadium. A nice change of pace for the players was that everyone got his own room. The tough part was that besides training each day and meals—during which players had to eat two meters apart—they had to stay in them. There was 24-hour security on each of the three floors occupied by players and coaches, as well as outside the hotel. They had their own entrance, and anyone going in or out had their temperature taken.

“We all got tested and we were all negative, but we still couldn’t hang out in each other’s rooms, even though it was just us,” McKennie said. “Whenever we walked to the [practice] pitch, we had to wear a mask, even thought we’re still among ourselves. It needed to be done and we held to it."

Looming large was Borussia Dortmund. When Bundesliga play was suspended in March, it was in second place, four points behind Bayern. Schalke was in sixth, 12 points out of the last of four 2020–21 UEFA Champions League berths but holding on to the final ticket to the Europa League. When it comes to the Revierderby, however, the standings are usually just a detail. Dortmund-Schalke is a grudge match—yellow vs. blue, steel vs. coal—a backyard brawl between the two biggest, most historic clubs in a region of the country where Fußball is religion. Cut the distance between Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium and Auburn’s Jordan-Hare by more than 85%, then eliminate every U.S. sport but college football, and you’ll get an idea.

“We’re so close to each other. We call it the 'pott,'” McKennie said. As in, a boiling pot.

“We could literally play against Bayern and lose 5-0 and the fans wouldn’t give you any crap if the Dortmund game is next,” he explained. “Or two weeks before we play Dortmund, there will already be signs up in the stadium even when we’re playing someone else.”

That’s a lot to handle for a first game back after around two months on the couch.

“We would’ve preferred to start with another game. This is the biggest one we play during the season, and going into this game without having a test match, with just eight or nine days of team training, was really tough,” Schneider said.

But Dortmund faced the same adversity and would be missing stars Marco Reus and Axel Witsel entirely and, for most of the game, Jadon Sancho. Rust was a given, and both teams prepared the best they could for the unique unknown. This Revierderby was about more than the Ruhr. It was the marquee matchup of the Bundesliga’s first week back—of world soccer’s return—and no one was sure quite how to approach it. Dortmund sporting director Michael Zorc said, “A derby without fans makes your heart bleed.”

Schalke made the shorter-than-usual drive in two buses instead of one, and every player was masked and in a row by himself. Schneider and Jobst were allotted two of the four tickets available to the Schalke front office, and they drove in their own cars. In Dortmund, the DFL’s new protocol was in place. Temperatures were taken. Hands were sanitized. Players split up into multiple locker rooms to dress, and the rest of the 322 people allowed inside the Westfalenstadion went about their business.

The DFL’s 50-page plan outlines precisely who is permitted in what part of the stadium during seven 90–120 minute increments all the way up to an hour and a half following the final whistle.

There were eight groundskeepers, three photographers, four ball boys and four medical personnel. Security guards, doping control, journalists, police and coaches were all accounted for. Balls were sprayed down, and the teams took the field separately. The starters without masks headed toward the center, while the masked reserves sat separated in the first row of spectator seats, rather than on the bench.

The whistle blew, and soccer was back. Sort of.

“The biggest difference was just going out not having any fans there,” McKennie said. “Obviously we had to take precautions wearing masks but other than that, it was a quiet atmosphere that definitely took getting used to.

“But I guess because I hadn’t played in such a long time, it felt like the new normal,” he added. “It’s still 11 v. 11 on the field, and you have to figure out everything on the field. The fans don’t play it for you.”

There’s no social distancing in soccer. It’s a contact sport. There are tackles, collisions, and plenty of jostling on set pieces. McKennie said that was on his mind in the early going.

“I thought about it a bit on a corner because I didn’t know, are we allowed to be touching them? You want to feel where the person is and I thought for a second, can we even do this?” McKennie recalled. “But then I was like, what am I talking about? It’s a game. Of course I can do this.”

Players were asked not to shake hands or celebrate with each other after goals, but when Schalke protested the lack of a call for a perceived foul against Amine Harit late in the first half, any hope for social distancing between players and referee was lost. The foul wasn’t called, and a couple of minutes later Dortmund was sort of celebrating a second goal and a 2–0 halftime lead.

Schalke was second-best all afternoon, to just about every ball and on just about every transition. McKennie, a holding midfielder, was left desperately chasing far too often as the Schalke back four buckled, and Dortmund was ruthless with the scoring chances it had. Schalke manager David Wagner, the son of an American father who was born in Frankfurt but played a handful of times for the USA in the 1990s, now knows how much work he has ahead of him.

It was a heavy defeat. Normally, that would dominate the headlines. And it may have in Gelsenkirchen. But for the rest of the country and the world, the score was secondary. Photos of Dortmund’s postgame salute to the empty south stand were everywhere, and the Bundesliga could breathe a sigh of relief.

“We started very early with the work on it, and now there is proof. The concept now shows that it can work, and now every other league in Europe has a model,” Jobst said.

Added Schneider: “Now we proved that the Bundesliga can do it. We are on the right track. We know it’s going to be tough, though. We still have eight match days to go, but we have fingers crossed and we are confident we can make it.”

As detailed and comprehensive as the DFL’s plan may be, it’s also quite fragile. Positive coronavirus tests at 2. Bundesliga club Dynamo Dresden forced the entire team into quarantine, meaning it couldn’t restart its season last weekend. A couple more of those at other teams, and the entire match schedule might fall apart (Jobst said the league season could be completed in July if necessary).

The return plan also could fall prey to the covidiot. They have them even in Germany. Hertha Berlin forward Salomon Kalou was suspended in early May after posting a video that showed him interrupting a teammate’s coronavirus test, shaking hands with others and generally breaking just about every social distancing rule there is. Then last week, Augsburg manager Heiko Herrlich was forced to miss his club’s reopener after he broke the hotel quarantine to buy toothpaste. Both were caught before too much damage was done. But the next mistake could have significant consequences.

That’s why even players who test negative still are separated in hotel rooms and on buses. It’ll be the local health authorities, not the club or DFL, who decides what happens, and who’s quarantined for how long, if someone tests positive.

“This concept needs the support of every single club, every single player, staff member, coach. Everybody has to be aware that he’s responsible for the whole concept,” Schneider said.

Schalke players will stay home this week and get tested one more time before Sunday’s home match against Augsburg. The Veltins-Arena will be just as quiet as the Westfalenstadion, but the empty seats will be Schalke blue, at least, and there will be a banner thanking the club’s fans hung at one end. McKennie & Co. have fallen into eighth and have plenty to play for and more than enough to motivate them. These ghost games count, despite the many strange or uncomfortable moments therein.

“I was taking to Gio Reyna after the [Dortmund] game, and we got told to back up because we were, without thinking, getting a bit closer. You subconsciously get a little closer, so we got told to keep our distance,” McKennie said when asked to recall the incident last weekend that summed up the experience.

Keeping their distance in the sport that brings the world together—that’ll be the challenge over the next month-plus.

“It’s something that I think the world and places back in America have to really follow the rules and the regulations as well as we did over here, and that’s why the Bundesliga is starting up,” McKennie said. “Many teams are in crisis, and many teams really need it. The league needs it, and obviously it’s all about the safety first, and if the players are willing to do it. They really wanted to do it.”

What did the Bundesliga's return really look like, and how was it able to happen? From the atypical bus ride to a derby to the meticulous hotel and stadium protocol, take a detailed view of what's gone into bringing the German league back.

In seasons past, you didn’t need to hear the din coming from the Westfalenstadion’s towering south stand, which can hold 25,000, to get the pulse racing on derby day. The buzz began well in advance, during the 20-mile drive between Gelsenkirchen and Dortmund. They’re smaller cities on a national scale, but they’re at the heart of western Germany’s bustling, congested and soccer-mad Ruhr region. And they’re at opposite ends of the Bundesliga’s most heated rivalry—the Revierderby between Schalke 04 and Borussia Dortmund.

“Normally on a Saturday morning on the Autobahn, you can see fans traveling from one city to the other. Especially in western Germany. You see fans with every color, and there’s a lot of traffic in front of the stadium,” said Jochen Schneider, Schalke’s director of sport.

Said Schalke’s American midfielder, Weston McKennie, “Whenever you are driving to that game, you see police escorts and a bunch of fans on the road. You see fans when you get there. You have Dortmund fans throwing fingers at you, and maybe occasionally, if they really have the balls, they’ll throw a beer at the bus.”

The rivals met again last Saturday, in the 156th competitive Revierderby and also the first of its kind. Dortmund’s south stand—the Yellow Wall—was empty. And so were the Autobahn 40 and the rest of the roads. The bottlenecks, spiteful gestures and projectiles were absent.

“It was totally different. There was nobody on the street,” Schneider said.

Added McKennie: “There was no need for a police escort or security. It was pretty quiet. The fans definitely are a big part of that game. Driving there, you see your fans and their fans, seeing them go at it with each other at times. It definitely riles you up for the game and gets you excited even more than usual. It was a big factor that was missing.”

And it would get only stranger from there. Saturday’s Revierderby was what the Germans call a “Geisterspiel”—a “ghost game.” It was soccer without any of the traditional sound and fury that help make it the most popular sport in the world. There were 22 men on the Westfalenstadion field, plus officials. There were 90 minutes of play, with shots and goals and all the technical trappings of the game. But the atmosphere—the communal aspect of match day so crucial to Germans’ consumption of the sport—was missing. There was no player procession, and no pregame photo or captains’ handshake. The stands were barren and banner-free, the only sound in the 81,365-seat arena coming from shouting players and the occasional ‘thwack’ of the ball against the post or rigging.

The surroundings were so surreal that Dortmund manager Lucien Favre asked a sport psychologist to help prepare his players during the days preceding the game. It may have helped. His side won emphatically, 4–0.

But that relative silence and those empty seats were ironic reminders of how much scrutiny was focused on the Revierderby and the rest of last weekend’s Bundesliga slate. These Geisterspiels represented a massive, albeit abnormal step toward a long-awaited return to normalcy, and they were being watched around the world. The Bundesliga and its second tier, the 2. Bundesliga, were the first leagues of global import to return to action following a break necessitated by the coronavirus pandemic (the Bundesliga is the second-best attended professional league on the planet behind the NFL), and they were doing so well before other major circuits in Europe and the USA.

The Bundesliga’s complex return-to-play plan and the Geisterspiels would serve either as a road map for others, or as a warning; as an homage to discipline, cooperation and the power of protocol, or as a symbol of hubris and greed. The final scores were far from the only results being followed.

“We wanted to play and finish up the season and get it over with, and we were willing to sacrifice what we needed to make that happen,” McKennie told Sports Illustrated. “I think there’s a feeling here like, everyone’s going to follow your pathway and how we did it, and how we were able to minimize [the virus] and continue on with everyday life.”

McKennie, an FC Dallas product, is one of several noteworthy members of a refreshed U.S. national team player pool now working in Germany, making the Bundesliga a league of significant interest for U.S. fans. Dortmund, which developed Christian Pulisic (now at Chelsea), features Gio Reyna, the 17-year-old son of U.S. legend Claudio Reyna who would’ve started the Revierderby if not for an injury suffered while warming up. Midfielder Tyler Adams (RB Leipzig), injured goalkeeper Zack Steffen (Fortuna Düsseldorf), striker Josh Sargent (Werder Bremen) and center back John Brooks (Wolfsburg) are among the other Bundesliga-based players likely to feature in the build-up to the 2022 World Cup.

German soccer’s open-minded outlook on American players—they’re relatively cheap compared to counterparts from more traditional powers—is emblematic of its analytical approach to so many facets of the game, from player development and marketing to this month’s return to the field. Last weekend’s matches were a triumph of organization and procedure, led by Deutsche Fussball Liga (DFL) executives who started working within days of the March shutdown, and backed by a government headed by a chancellor, Angela Merkel, who happens to hold a doctorate degree in quantum chemistry.

“That we’re allowed to play again boils down to German politics for managing this crisis, and the health system in Germany,” DFL CEO Christian Seifert told reporters. “If I were to name the number of tests that I was asked about in teleconferences with other professional leagues, with American professional leagues, with clubs from the NFL, the NHL, Major League Baseball and others, and I tell them how many tests are possible in Germany, they generally check, or there’s silence, because it’s just unimaginable in the situation over there.”

While U.S. sports officials ponder sending every team to Orlando or Las Vegas, while athletes there still haven’t returned to formal training, and while the government spins its wheels and debates the healing power of bleach, the situation isn’t dramatically better in Europe. The soccer leagues in France, Netherlands, Belgium and Scotland already have canceled the remainder of their 2019–20 seasons. England’s Premier League, Spain’s La Liga and Italy’s Serie A now are targeting a mid-June kickoff. Meanwhile, the Bundesliga hopes to have its season finished—each team has eight games remaining—by the end of next month.

From the start, Germany weathered the pandemic better than its peers. According to the World Health Organization, it has suffered some 8,100 coronavirus deaths. The countries that host Europe’s other “big” soccer leagues—France, Italy, Spain and the U.K.—have each endured more than three times that figure. German society has been gradually reopening since late April. But that doesn’t mean the public was firmly behind the Bundesliga’s restart. Some felt it signaled misplaced priorities, while others were offended by the Geisterspiel idea.

“The overall opinion in Germany was not that positive,” Schneider said. “People are fighting for their jobs. Kids cannot go to school. Why on earth should the football players be allowed to play their games again? We needed a strong concept to convince the politicians.”

A lot was riding on that concept and then last weekend’s implementation. The Bundesliga is popular and relatively wealthy, but its individual members aren’t necessarily among sports’ most valuable or profitable franchises. On Forbes’ most recent list of the world’s 50 most valuable teams, only seven-time defending champion Bayern Munich (No. 17) warranted a place. And according to the Deloitte's 2020 Football Money League report, only Bayern (No. 4), Dortmund (No. 12) and Schalke (No. 15) are among soccer’s top 25 revenue-producing clubs. The Bundesliga is broadcast in more than 200 countries, but it can’t compete with England’s Premier League on rights fees, and only Bayern has anything close to the global cachet enjoyed by the likes of Barcelona and Real Madrid. Further, German teams are subject to a rule requiring a majority of each club to be owned by its members, limiting the influence a super-wealthy oligarch or government can have over its finances.

In other words, despite the Bundesliga’s size and popularity, returning to the field sooner rather than later was a matter of economic survival. Seifert said canceling the remainder of the season would cost some $800 million.

“Every football club, not only Schalke, survives on TV revenue. Without being able to finish the season, many professional football clubs would have been in big trouble from a financial stability side,” Schalke director of marketing and communications Alexander Jobst said. “Schalke is an independent football club. We belong to our members. We don’t have foreign investors, so we belong even more to our TV revenue and sponsorship and ticket revenue. If this disappears, we don’t have an investor who pumps in millions of Euros to survive.”

Jobst estimated that a third of Schalke’s revenue comes from TV, a third from sponsorship (which is tied to TV), and a third from ticketing and match day. Playing in an empty stadium eliminates the latter, which at Schalke’s Veltins-Arena comes to around $2.2 million per game. Fans who haven’t asked for their season-ticket money back get a shirt featuring the emblem of the club’s “Only Together” coronavirus campaign.

So a TV product was created. The DFL huddled with health authorities, municipalities, its TV partners and clubs to create an exhaustive return-to-play plan—the English version is 50 pages long—that was approved by the German government on May 6. It involved a lot of people, many moving parts and would require significant discipline, especially from the players. They would be tested at least twice a week (the DFL is paying for around 20,000 tests, which Seifert said would compose no more than 0.4% of Germany’s capacity), and would have to be quarantined for a week preceding the first game. Afterward, the plan forbids contact with neighbors or visitors and the use of public transportation, among other activities.

“We told them, you have to create two quarantine situations, one at home and the other here at the training ground. We have to avoid as much as possible any contact with other people,” Schneider said.

The club went so far as to do grocery shopping for players who were unable or reluctant to do so. Their items were waiting for them at Schalke’s facility following practice. Jobst said there even were opportunities for club sponsors, who were searching for ways to be involved during the shutdown, to help feed and support the players.

“Schalke in general has been doing a really good job, even though sometimes there might be a feeling of, ‘Do we really have to do this?’ But at the same time, you’re thankful for it because it’s really going to protect you,” McKennie said.

“The Germans are very disciplined,” he continued. “When they have something they want to do or they have a system they need to put in place, or certain rules, they’re really strict about them and most people here will follow the rules as much as they can. That’s just kind of how Germans are and how they’re brought up.”

Jobst and Schneider said that worried players were given the opportunity to back out of the return to play without repercussion, but all were willing to comply. They entered quarantine at the beginning of last week inside a Courtyard Marriott located just a block north of Schalke’s stadium. A nice change of pace for the players was that everyone got his own room. The tough part was that besides training each day and meals—during which players had to eat two meters apart—they had to stay in them. There was 24-hour security on each of the three floors occupied by players and coaches, as well as outside the hotel. They had their own entrance, and anyone going in or out had their temperature taken.

“We all got tested and we were all negative, but we still couldn’t hang out in each other’s rooms, even though it was just us,” McKennie said. “Whenever we walked to the [practice] pitch, we had to wear a mask, even thought we’re still among ourselves. It needed to be done and we held to it."

Looming large was Borussia Dortmund. When Bundesliga play was suspended in March, it was in second place, four points behind Bayern. Schalke was in sixth, 12 points out of the last of four 2020–21 UEFA Champions League berths but holding on to the final ticket to the Europa League. When it comes to the Revierderby, however, the standings are usually just a detail. Dortmund-Schalke is a grudge match—yellow vs. blue, steel vs. coal—a backyard brawl between the two biggest, most historic clubs in a region of the country where Fußball is religion. Cut the distance between Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium and Auburn’s Jordan-Hare by more than 85%, then eliminate every U.S. sport but college football, and you’ll get an idea.

“We’re so close to each other. We call it the 'pott,'” McKennie said. As in, a boiling pot.

“We could literally play against Bayern and lose 5-0 and the fans wouldn’t give you any crap if the Dortmund game is next,” he explained. “Or two weeks before we play Dortmund, there will already be signs up in the stadium even when we’re playing someone else.”

That’s a lot to handle for a first game back after around two months on the couch.

“We would’ve preferred to start with another game. This is the biggest one we play during the season, and going into this game without having a test match, with just eight or nine days of team training, was really tough,” Schneider said.

But Dortmund faced the same adversity and would be missing stars Marco Reus and Axel Witsel entirely and, for most of the game, Jadon Sancho. Rust was a given, and both teams prepared the best they could for the unique unknown. This Revierderby was about more than the Ruhr. It was the marquee matchup of the Bundesliga’s first week back—of world soccer’s return—and no one was sure quite how to approach it. Dortmund sporting director Michael Zorc said, “A derby without fans makes your heart bleed.”

Schalke made the shorter-than-usual drive in two buses instead of one, and every player was masked and in a row by himself. Schneider and Jobst were allotted two of the four tickets available to the Schalke front office, and they drove in their own cars. In Dortmund, the DFL’s new protocol was in place. Temperatures were taken. Hands were sanitized. Players split up into multiple locker rooms to dress, and the rest of the 322 people allowed inside the Westfalenstadion went about their business.

The DFL’s 50-page plan outlines precisely who is permitted in what part of the stadium during seven 90–120 minute increments all the way up to an hour and a half following the final whistle.

There were eight groundskeepers, three photographers, four ball boys and four medical personnel. Security guards, doping control, journalists, police and coaches were all accounted for. Balls were sprayed down, and the teams took the field separately. The starters without masks headed toward the center, while the masked reserves sat separated in the first row of spectator seats, rather than on the bench.

The whistle blew, and soccer was back. Sort of.

“The biggest difference was just going out not having any fans there,” McKennie said. “Obviously we had to take precautions wearing masks but other than that, it was a quiet atmosphere that definitely took getting used to.

“But I guess because I hadn’t played in such a long time, it felt like the new normal,” he added. “It’s still 11 v. 11 on the field, and you have to figure out everything on the field. The fans don’t play it for you.”

There’s no social distancing in soccer. It’s a contact sport. There are tackles, collisions, and plenty of jostling on set pieces. McKennie said that was on his mind in the early going.

“I thought about it a bit on a corner because I didn’t know, are we allowed to be touching them? You want to feel where the person is and I thought for a second, can we even do this?” McKennie recalled. “But then I was like, what am I talking about? It’s a game. Of course I can do this.”

Players were asked not to shake hands or celebrate with each other after goals, but when Schalke protested the lack of a call for a perceived foul against Amine Harit late in the first half, any hope for social distancing between players and referee was lost. The foul wasn’t called, and a couple of minutes later Dortmund was sort of celebrating a second goal and a 2–0 halftime lead.

Schalke was second-best all afternoon, to just about every ball and on just about every transition. McKennie, a holding midfielder, was left desperately chasing far too often as the Schalke back four buckled, and Dortmund was ruthless with the scoring chances it had. Schalke manager David Wagner, the son of an American father who was born in Frankfurt but played a handful of times for the USA in the 1990s, now knows how much work he has ahead of him.

It was a heavy defeat. Normally, that would dominate the headlines. And it may have in Gelsenkirchen. But for the rest of the country and the world, the score was secondary. Photos of Dortmund’s postgame salute to the empty south stand were everywhere, and the Bundesliga could breathe a sigh of relief.

“We started very early with the work on it, and now there is proof. The concept now shows that it can work, and now every other league in Europe has a model,” Jobst said.

Added Schneider: “Now we proved that the Bundesliga can do it. We are on the right track. We know it’s going to be tough, though. We still have eight match days to go, but we have fingers crossed and we are confident we can make it.”

As detailed and comprehensive as the DFL’s plan may be, it’s also quite fragile. Positive coronavirus tests at 2. Bundesliga club Dynamo Dresden forced the entire team into quarantine, meaning it couldn’t restart its season last weekend. A couple more of those at other teams, and the entire match schedule might fall apart (Jobst said the league season could be completed in July if necessary).

The return plan also could fall prey to the covidiot. They have them even in Germany. Hertha Berlin forward Salomon Kalou was suspended in early May after posting a video that showed him interrupting a teammate’s coronavirus test, shaking hands with others and generally breaking just about every social distancing rule there is. Then last week, Augsburg manager Heiko Herrlich was forced to miss his club’s reopener after he broke the hotel quarantine to buy toothpaste. Both were caught before too much damage was done. But the next mistake could have significant consequences.

That’s why even players who test negative still are separated in hotel rooms and on buses. It’ll be the local health authorities, not the club or DFL, who decides what happens, and who’s quarantined for how long, if someone tests positive.

“This concept needs the support of every single club, every single player, staff member, coach. Everybody has to be aware that he’s responsible for the whole concept,” Schneider said.

Schalke players will stay home this week and get tested one more time before Sunday’s home match against Augsburg. The Veltins-Arena will be just as quiet as the Westfalenstadion, but the empty seats will be Schalke blue, at least, and there will be a banner thanking the club’s fans hung at one end. McKennie & Co. have fallen into eighth and have plenty to play for and more than enough to motivate them. These ghost games count, despite the many strange or uncomfortable moments therein.

“I was taking to Gio Reyna after the [Dortmund] game, and we got told to back up because we were, without thinking, getting a bit closer. You subconsciously get a little closer, so we got told to keep our distance,” McKennie said when asked to recall the incident last weekend that summed up the experience.

Keeping their distance in the sport that brings the world together—that’ll be the challenge over the next month-plus.

“It’s something that I think the world and places back in America have to really follow the rules and the regulations as well as we did over here, and that’s why the Bundesliga is starting up,” McKennie said. “Many teams are in crisis, and many teams really need it. The league needs it, and obviously it’s all about the safety first, and if the players are willing to do it. They really wanted to do it.”

0 Comments