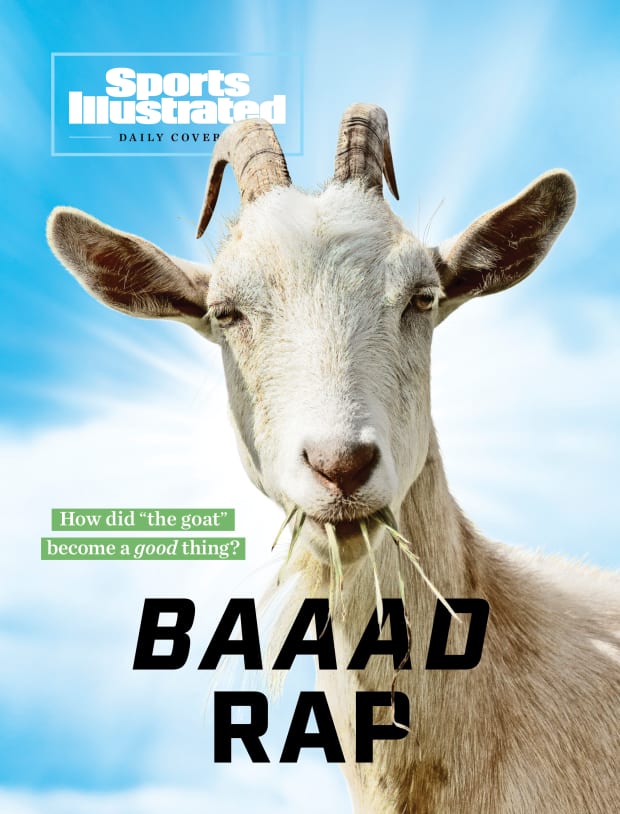

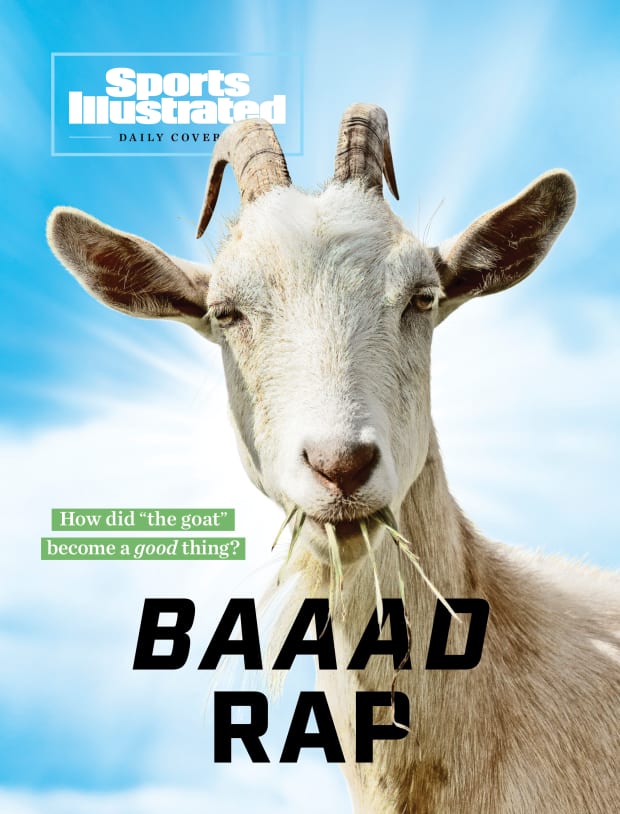

He used to be the fall guy. Buckner. Bartman. Now he is the greatest. MJ. Tiger. How did this barnyard pejorative turn into a boast?

“If you don't make it, you're the goat. If you make it, you’re the greatest of all time." —NFL quarterback Doug Williams, December 1988

Before people said Tom Brady had surpassed Joe Montana as football’s GOAT … before golf fans argued about whether Tiger or the Golden Bear is the GOAT … before you could type

goat.com into your browser and get a site trying to sell you Air Jordans … before a clothier named Greyson pitched an “iconic GOAT polo” shirt as “everything that we stand for and everything that we want to be” … before you could watch Jeopardy!: GOAT … before LeBron James vs. Michael Jordan became the GOAT of GOAT arguments … before all that, the last thing you wanted to be in sports was the goat.A goat was the opposite of a hero. A goat cost his team the game. Fred Merkle, whose baserunning error helped cost the New York Giants the 1908 pennant, was a goat. Fred Brown, who passed to the wrong team at the end of the '82 NCAA men’s basketball championship game, was a goat. Every Cubs fan knew Leon Durham was a goat, and every Cowboys fan knew Jackie Smith was too. When Chris Webber called a timeout that his Michigan team didn’t have in the 1993 title game, newspapers across the country declared he was “the goat” or “wore the goat horns.”

Like some of Jordan’s best dunks, the word goat has done the rarely seen etymological 180: It now means almost the exact opposite of what it used to mean. If you weren’t paying attention, you might have missed the change. A few years ago, former NBA player Craig Ehlo was watching a Finals game when his son Austin declared “LeBron is the GOAT.” Ehlo was confused; he had never heard the acronym for greatest of all time before. Ehlo was the Cavalier guarding Jordan when MJ hit The Shot, in 1989, and at the time Ehlo seemed like the goat on that play—but as it turns out, Jordan was. If that seems weird, consider Mariano Rivera’s journey: He went from goat (in the '97 and 2001 postseasons) to the GOAT of relief pitching.

Now, GOATs are everywhere, often in emoji form. When Phil Mickelson announced that Brady would be his partner in last weekend’s charity match against Tiger Woods and Peyton Manning, he tweeted, “I’m bringing a 🐐.”

“I’m feeling a lot of energy around the GOAT,” says LL Cool J, whose 2000 record, G.O.A.T., helped spread the GOAT gospel. “People are going down the rabbit hole and doing their own research. … This did emanate from LL.”

Well, it sort of did. Muhammad Ali called himself the Greatest of All Time first, and he named his company GOAT. (Authentic Brands Group, which owns SI, also handles licensing for Ali’s estate.) But LL helped take it mainstream. So ride that goat down the rabbit hole with us. This is not just a semantic discussion; the word’s evolution mimics America’s.

LL Cool J had two goats in mind when he dropped G.O.A.T. One was Ali. The other was Earl (the Goat) Manigault, a New York streetball legend. To understand how goats became GOATs, you must understand both the GOAT and the goat.

***

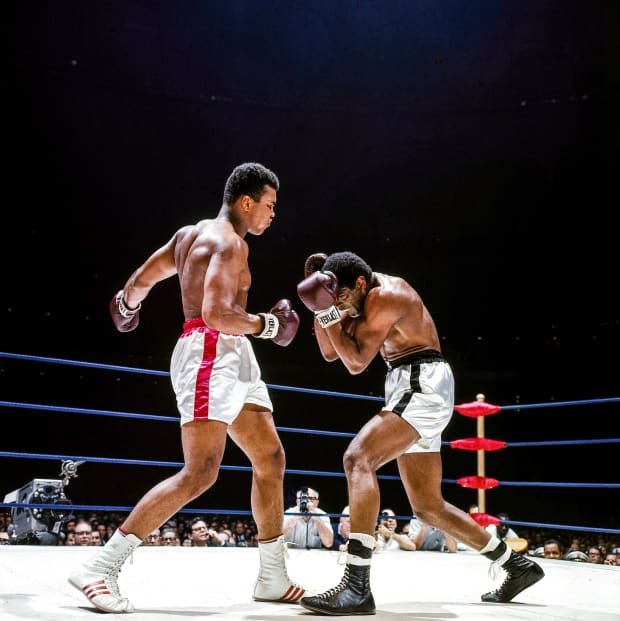

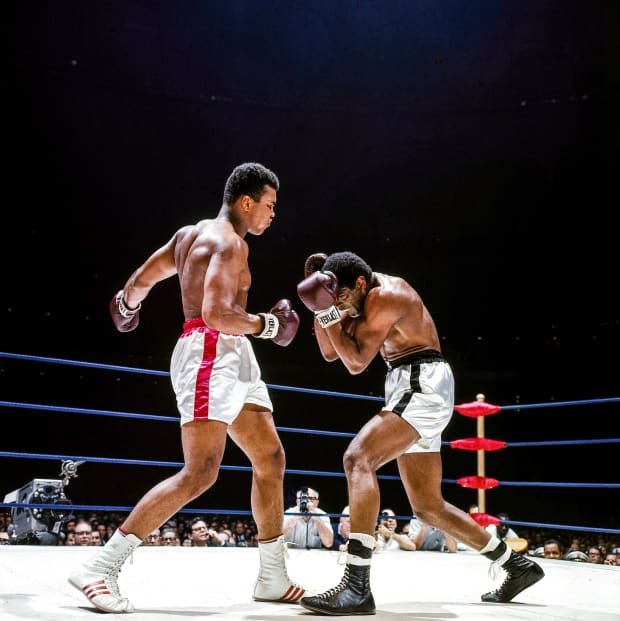

America had never seen anything like Muhammad Ali in the mid-1960s: perpetually loud, relentlessly self-promoting, declaring himself the king before he ascended to the throne. (“I am the greatest,” Ali said later in life. “I said that even before I knew I was.”) He was mesmerizing and defiant, a black man who made white America extremely uncomfortable and knew it.

The nation’s sports stars were supposed to speak like Joe DiMaggio: “I'm just a ballplayer with one ambition, and that is to give all I've got to help my ball club win.” Or Johnny Unitas: “There is a difference between conceit and confidence. Conceit is bragging about yourself. Confidence means you believe you can get the job done.”

Ali mixed conceit and confidence and poured it in America’s glass. Joe Namath did, too. But they were outliers; most self-promotion had to be subtle, especially if it came from a person of color, but even if it didn’t. After the Beatles broke up, with Ali’s voice ringing in his ear, John Lennon wrote a song mocking his own image called “I’m the Greatest.” But Lennon didn’t want to record it himself. He feared people would think he was serious. (He'd already gotten in trouble in the U.S. for declaring the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.”) So Lennon gave “I’m the Greatest” to Ringo Starr. Nobody could think Ringo was bragging.

Bragging brought blowback. For every Ali or Namath, there was Reggie Jackson, facing severe backlash for (allegedly) saying he was “the straw that stirs the drink.” The media controlled the narratives, the media skewed heavily toward older white men, and corporate America wanted its pitch people to appear wholesome and unthreatening. In 1984, Carl Lewis won four Olympic gold medals in Los Angeles, but he failed to earn a single national endorsement because people thought he was cocky. Smiling teen gymnast Mary Lou Retton ended up on a box of Wheaties instead. Seven years later, Rickey Henderson broke Lou Brock’s career stolen bases record and declared, “Today, I am the greatest of all time!” That same day, Nolan Ryan threw his seventh no-hitter, and more than one pundit celebrated the quiet Ryan's upstaging the brash Henderson.

The NBA was rising as a cultural force, but not in the same way we see today: Fans were told to choose between black (Magic Johnson) and white (Larry Bird), and part of Magic’s crossover appeal was his disarming smile. Michael Jordan bridged that gap, but he did it with a carefully crafted image. He talked trash relentlessly in practice and games, but almost never when the public could hear him. He dressed dapperly to press conferences and famously avoided controversy. When Bulls executive Steve Schanwald helped design the base of the Jordan statue that has rested outside the United Center since the arena opened in 1994, he was thinking of MJ's impeccability on and off the court: “I didn’t think it would ever be possible to exceed his level of excellence.”

The inscription: The best there ever was, the best there ever will be. “I don’t think Michael has ever even referred to himself as the GOAT,” Schanwald says. “Was that phrase even used?” Not really. When Jordan hit a playoff game-winner over the Cavs’ Gerald Wilkins one year before his monument went up, the Associated Press declared, “This time, Gerald Wilkins was the goat.” There were goats but no GOATs, except for Ali. American stars were supposed to act humble. And this brings us to Earl Manigault.

***

The goat never played in the NBA. Drug addiction derailed him. His legend is not from being the GOAT—that nickname likely came from a mispronunciation of his last name—but from being a fearless star from the streets. He was a 6' 1" guard who drove in and soared over the game’s giants in the 1960s, playing a form of basketball that was not just great, it was expressive. He was hip-hop before hip-hop.

“I mean, look: One thing people gotta understand about the mentality of hip-hop is that self-proclaimed greatness comes with the territory,” says LL Cool J. “Mainstream people from the outside looking in see it as overconfidence or whatever. But in hip-hop, when you’re coming from nothing, from a neighborhood where nobody pays you attention, you want to be the greatest, the GOAT. It’s the spirit of the culture.”

Cultural changes take time. The first Grammy for Best Rap Performance was awarded in 1989. Best Rap Album did not become a category until '96. In 2004—20 years after Carl Lewis was a corporate outcast—sprinter Maurice Greene showed up to the Sydney Olympics sporting a GOAT tattoo. His friend Larry Wade had helped design it, and both men saw it as self-actualization more than self-promotion.

“I was watching Muhammad Ali stuff,” Greene says. “A lot of people will make you seem arrogant if you’re calling yourself the greatest. But when you’re competing at this high of a level, you have to believe you’re that good. There are not a lot of times when you can actually believe wholeheartedly you are that person. You have to profess it if you want to become it.”

Greene won gold in Sydney two weeks after LL released G.O.A.T. As hip-hop elbowed its way to the forefront of American music, its culture permeated sports. Large swaths of white America started to accept it. And then embrace it.

***

Looking back, October 2003 was the month when goat peaked and GOAT started to surpass it. GUY WHO WRANGLED FOR FOUL BALL BECOMES NATIONAL GOAT, The Charlotte Observer declared shortly after Steve Bartman aided, however slightly, in a Cubs loss. But that same month, LeBron James made his NBA debut with a CHOSEN 1 tattoo and a record-breaking Nike deal. He has never shied away from calling himself King James. Also in October 2003: ESPN debuted its debate show, Cold Pizza, the forerunner to First Take. We were just entering a world in which Skip and Stephen A. would argue incessantly about GOATs.

The advent of social media—self-expression for the masses —multiplied such debates exponentially. But social media also required shorthand. Greatest of All Time took up 20 precious characters out of the 140 Twitter originally allowed. A goat emoji requires just one.

Emoji, not English, is the world’s most common language, and just as eggplant and peach emojis rarely represent produce, emoji goats are rarely actually farm animals. Keith Broni, the deputy emoji officer of Emojipedia, says that when ESPN debuted The Last Dance on April 19, Twitter saw a 79% increase in the use of the goat emoji—and that does not count the goat wearing a No. 23 jersey, which follows every #LastDance hashtag. Those MJ goats are called hashflags, and they are generally purchased as part of an advertising campaign. There is no hashflag for The best there ever was, the best there ever will be.

Twenty years ago, LL Cool J rapped, “Ain’t no rapper could do what I do.” But now he says, “Every other day, you got a rapper coming out with an album called GOAT. It’s actually kind of funny. … I made the album. I wrote the song. I started referring to myself as the GOAT. I had no idea it would become a part of pop culture.”

America’s ever-increasing desires to hype, shorten and argue are all captured by a 🐐. And while some would bemoan the chest-pounding of modern culture, there is another way to look at the rise of GOAT over goat. Says Ehlo: “Your signature moment in sports should be on the winning side.” The original goat was a derivative of scapegoat, and the world has enough of those. At least GOAT, unlike goat, is celebratory.

Of course, the old goat still surfaces sometimes. Last year, The Sacramento Bee announced: BILL BUCKNER, FORMER WORLD SERIES GOAT AND ALL-STAR, DIES AT 69. One might say that Buckner, pushing 70, was grandfathered in. But mostly, today, goat means GOAT.

In 2018, James looked back on his Cavaliers’ upset two years earlier of the 73-win Warriors and said, “That one right there made me the greatest player of all time. That’s what I felt.” The first part of the quote became the headline, but the second part captured how LL Cool J and Maurice Greene view GOAT. James may or may not be the greatest player of all time, but he is damn well supposed to think he is.

Why be a sheep when you can be the 🐐, golfer Chase Koepka asks in his Twitter bio—and the fact that Chase is not even the greatest golfing Koepka of all time is beside the point. GOAT epitomizes the shoot-your-shot mentality. LL Cool J and Greene are adamant that the world is full of GOATs.

“Does what Steve Jobs created make Leonardo da Vinci any less astounding as an individual?” LL asks. “You gotta look at context and time. How far did they move whatever they’re doing forward? Artists learn from artists. We don’t know how many times Usain Bolt looked at Maurice Greene and identified things he could do better. He got his hands on better cleats, surfaces changed. … You understand what I’m saying? It’s all relative. It’s never about any one person being the greatest, greatest, greatest of all time. People accomplish different things.”

If you love basketball, you admire MJ and LeBron, but also Kobe and Wilt and Kareem, and you may find yourself agreeing with LL. The more GOATs, the better. Then again, Ali also said, “I’m not the greatest. I’m the double greatest.” 🐐🐐

He used to be the fall guy. Buckner. Bartman. Now he is the greatest. MJ. Tiger. How did this barnyard pejorative turn into a boast?

“If you don't make it, you're the goat. If you make it, you’re the greatest of all time." —NFL quarterback Doug Williams, December 1988

Before people said Tom Brady had surpassed Joe Montana as football’s GOAT … before golf fans argued about whether Tiger or the Golden Bear is the GOAT … before you could type goat.com into your browser and get a site trying to sell you Air Jordans … before a clothier named Greyson pitched an “iconic GOAT polo” shirt as “everything that we stand for and everything that we want to be” … before you could watch Jeopardy!: GOAT … before LeBron James vs. Michael Jordan became the GOAT of GOAT arguments … before all that, the last thing you wanted to be in sports was the goat.

A goat was the opposite of a hero. A goat cost his team the game. Fred Merkle, whose baserunning error helped cost the New York Giants the 1908 pennant, was a goat. Fred Brown, who passed to the wrong team at the end of the '82 NCAA men’s basketball championship game, was a goat. Every Cubs fan knew Leon Durham was a goat, and every Cowboys fan knew Jackie Smith was too. When Chris Webber called a timeout that his Michigan team didn’t have in the 1993 title game, newspapers across the country declared he was “the goat” or “wore the goat horns.”

Like some of Jordan’s best dunks, the word goat has done the rarely seen etymological 180: It now means almost the exact opposite of what it used to mean. If you weren’t paying attention, you might have missed the change. A few years ago, former NBA player Craig Ehlo was watching a Finals game when his son Austin declared “LeBron is the GOAT.” Ehlo was confused; he had never heard the acronym for greatest of all time before. Ehlo was the Cavalier guarding Jordan when MJ hit The Shot, in 1989, and at the time Ehlo seemed like the goat on that play—but as it turns out, Jordan was. If that seems weird, consider Mariano Rivera’s journey: He went from goat (in the '97 and 2001 postseasons) to the GOAT of relief pitching.

Now, GOATs are everywhere, often in emoji form. When Phil Mickelson announced that Brady would be his partner in last weekend’s charity match against Tiger Woods and Peyton Manning, he tweeted, “I’m bringing a 🐐.”

“I’m feeling a lot of energy around the GOAT,” says LL Cool J, whose 2000 record, G.O.A.T., helped spread the GOAT gospel. “People are going down the rabbit hole and doing their own research. … This did emanate from LL.”

Well, it sort of did. Muhammad Ali called himself the Greatest of All Time first, and he named his company GOAT. (Authentic Brands Group, which owns SI, also handles licensing for Ali’s estate.) But LL helped take it mainstream. So ride that goat down the rabbit hole with us. This is not just a semantic discussion; the word’s evolution mimics America’s.

LL Cool J had two goats in mind when he dropped G.O.A.T. One was Ali. The other was Earl (the Goat) Manigault, a New York streetball legend. To understand how goats became GOATs, you must understand both the GOAT and the goat.

***

America had never seen anything like Muhammad Ali in the mid-1960s: perpetually loud, relentlessly self-promoting, declaring himself the king before he ascended to the throne. (“I am the greatest,” Ali said later in life. “I said that even before I knew I was.”) He was mesmerizing and defiant, a black man who made white America extremely uncomfortable and knew it.

The nation’s sports stars were supposed to speak like Joe DiMaggio: “I'm just a ballplayer with one ambition, and that is to give all I've got to help my ball club win.” Or Johnny Unitas: “There is a difference between conceit and confidence. Conceit is bragging about yourself. Confidence means you believe you can get the job done.”

Ali mixed conceit and confidence and poured it in America’s glass. Joe Namath did, too. But they were outliers; most self-promotion had to be subtle, especially if it came from a person of color, but even if it didn’t. After the Beatles broke up, with Ali’s voice ringing in his ear, John Lennon wrote a song mocking his own image called “I’m the Greatest.” But Lennon didn’t want to record it himself. He feared people would think he was serious. (He'd already gotten in trouble in the U.S. for declaring the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.”) So Lennon gave “I’m the Greatest” to Ringo Starr. Nobody could think Ringo was bragging.

Bragging brought blowback. For every Ali or Namath, there was Reggie Jackson, facing severe backlash for (allegedly) saying he was “the straw that stirs the drink.” The media controlled the narratives, the media skewed heavily toward older white men, and corporate America wanted its pitch people to appear wholesome and unthreatening. In 1984, Carl Lewis won four Olympic gold medals in Los Angeles, but he failed to earn a single national endorsement because people thought he was cocky. Smiling teen gymnast Mary Lou Retton ended up on a box of Wheaties instead. Seven years later, Rickey Henderson broke Lou Brock’s career stolen bases record and declared, “Today, I am the greatest of all time!” That same day, Nolan Ryan threw his seventh no-hitter, and more than one pundit celebrated the quiet Ryan's upstaging the brash Henderson.

The NBA was rising as a cultural force, but not in the same way we see today: Fans were told to choose between black (Magic Johnson) and white (Larry Bird), and part of Magic’s crossover appeal was his disarming smile. Michael Jordan bridged that gap, but he did it with a carefully crafted image. He talked trash relentlessly in practice and games, but almost never when the public could hear him. He dressed dapperly to press conferences and famously avoided controversy. When Bulls executive Steve Schanwald helped design the base of the Jordan statue that has rested outside the United Center since the arena opened in 1994, he was thinking of MJ's impeccability on and off the court: “I didn’t think it would ever be possible to exceed his level of excellence.”

The inscription: The best there ever was, the best there ever will be. “I don’t think Michael has ever even referred to himself as the GOAT,” Schanwald says. “Was that phrase even used?” Not really. When Jordan hit a playoff game-winner over the Cavs’ Gerald Wilkins one year before his monument went up, the Associated Press declared, “This time, Gerald Wilkins was the goat.” There were goats but no GOATs, except for Ali. American stars were supposed to act humble. And this brings us to Earl Manigault.

***

The goat never played in the NBA. Drug addiction derailed him. His legend is not from being the GOAT—that nickname likely came from a mispronunciation of his last name—but from being a fearless star from the streets. He was a 6' 1" guard who drove in and soared over the game’s giants in the 1960s, playing a form of basketball that was not just great, it was expressive. He was hip-hop before hip-hop.

“I mean, look: One thing people gotta understand about the mentality of hip-hop is that self-proclaimed greatness comes with the territory,” says LL Cool J. “Mainstream people from the outside looking in see it as overconfidence or whatever. But in hip-hop, when you’re coming from nothing, from a neighborhood where nobody pays you attention, you want to be the greatest, the GOAT. It’s the spirit of the culture.”

Cultural changes take time. The first Grammy for Best Rap Performance was awarded in 1989. Best Rap Album did not become a category until '96. In 2004—20 years after Carl Lewis was a corporate outcast—sprinter Maurice Greene showed up to the Sydney Olympics sporting a GOAT tattoo. His friend Larry Wade had helped design it, and both men saw it as self-actualization more than self-promotion.

“I was watching Muhammad Ali stuff,” Greene says. “A lot of people will make you seem arrogant if you’re calling yourself the greatest. But when you’re competing at this high of a level, you have to believe you’re that good. There are not a lot of times when you can actually believe wholeheartedly you are that person. You have to profess it if you want to become it.”

Greene won gold in Sydney two weeks after LL released G.O.A.T. As hip-hop elbowed its way to the forefront of American music, its culture permeated sports. Large swaths of white America started to accept it. And then embrace it.

***

Looking back, October 2003 was the month when goat peaked and GOAT started to surpass it. GUY WHO WRANGLED FOR FOUL BALL BECOMES NATIONAL GOAT, The Charlotte Observer declared shortly after Steve Bartman aided, however slightly, in a Cubs loss. But that same month, LeBron James made his NBA debut with a CHOSEN 1 tattoo and a record-breaking Nike deal. He has never shied away from calling himself King James. Also in October 2003: ESPN debuted its debate show, Cold Pizza, the forerunner to First Take. We were just entering a world in which Skip and Stephen A. would argue incessantly about GOATs.

The advent of social media—self-expression for the masses —multiplied such debates exponentially. But social media also required shorthand. Greatest of All Time took up 20 precious characters out of the 140 Twitter originally allowed. A goat emoji requires just one.

Emoji, not English, is the world’s most common language, and just as eggplant and peach emojis rarely represent produce, emoji goats are rarely actually farm animals. Keith Broni, the deputy emoji officer of Emojipedia, says that when ESPN debuted The Last Dance on April 19, Twitter saw a 79% increase in the use of the goat emoji—and that does not count the goat wearing a No. 23 jersey, which follows every #LastDance hashtag. Those MJ goats are called hashflags, and they are generally purchased as part of an advertising campaign. There is no hashflag for The best there ever was, the best there ever will be.

Twenty years ago, LL Cool J rapped, “Ain’t no rapper could do what I do.” But now he says, “Every other day, you got a rapper coming out with an album called GOAT. It’s actually kind of funny. … I made the album. I wrote the song. I started referring to myself as the GOAT. I had no idea it would become a part of pop culture.”

America’s ever-increasing desires to hype, shorten and argue are all captured by a 🐐. And while some would bemoan the chest-pounding of modern culture, there is another way to look at the rise of GOAT over goat. Says Ehlo: “Your signature moment in sports should be on the winning side.” The original goat was a derivative of scapegoat, and the world has enough of those. At least GOAT, unlike goat, is celebratory.

Of course, the old goat still surfaces sometimes. Last year, The Sacramento Bee announced: BILL BUCKNER, FORMER WORLD SERIES GOAT AND ALL-STAR, DIES AT 69. One might say that Buckner, pushing 70, was grandfathered in. But mostly, today, goat means GOAT.

In 2018, James looked back on his Cavaliers’ upset two years earlier of the 73-win Warriors and said, “That one right there made me the greatest player of all time. That’s what I felt.” The first part of the quote became the headline, but the second part captured how LL Cool J and Maurice Greene view GOAT. James may or may not be the greatest player of all time, but he is damn well supposed to think he is.

Why be a sheep when you can be the 🐐, golfer Chase Koepka asks in his Twitter bio—and the fact that Chase is not even the greatest golfing Koepka of all time is beside the point. GOAT epitomizes the shoot-your-shot mentality. LL Cool J and Greene are adamant that the world is full of GOATs.

“Does what Steve Jobs created make Leonardo da Vinci any less astounding as an individual?” LL asks. “You gotta look at context and time. How far did they move whatever they’re doing forward? Artists learn from artists. We don’t know how many times Usain Bolt looked at Maurice Greene and identified things he could do better. He got his hands on better cleats, surfaces changed. … You understand what I’m saying? It’s all relative. It’s never about any one person being the greatest, greatest, greatest of all time. People accomplish different things.”

If you love basketball, you admire MJ and LeBron, but also Kobe and Wilt and Kareem, and you may find yourself agreeing with LL. The more GOATs, the better. Then again, Ali also said, “I’m not the greatest. I’m the double greatest.” 🐐🐐

0 Comments