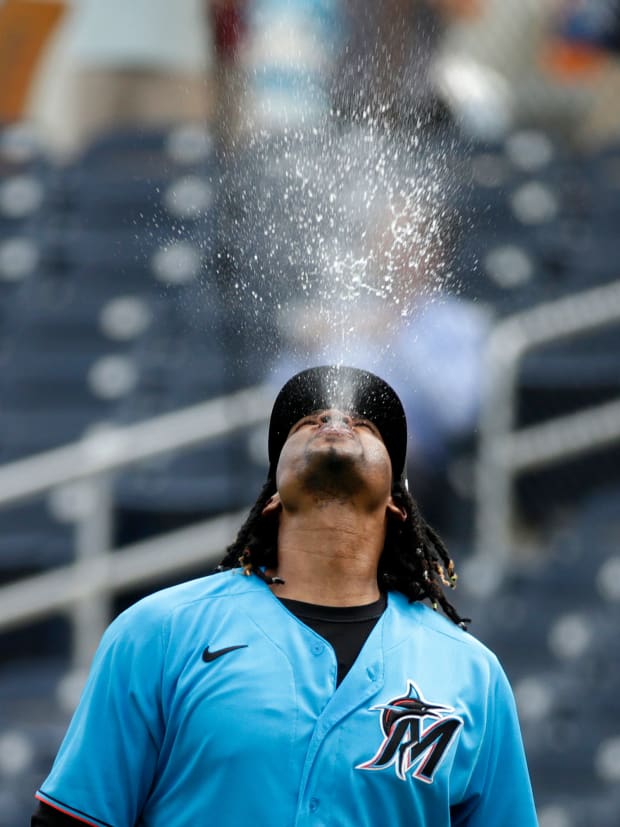

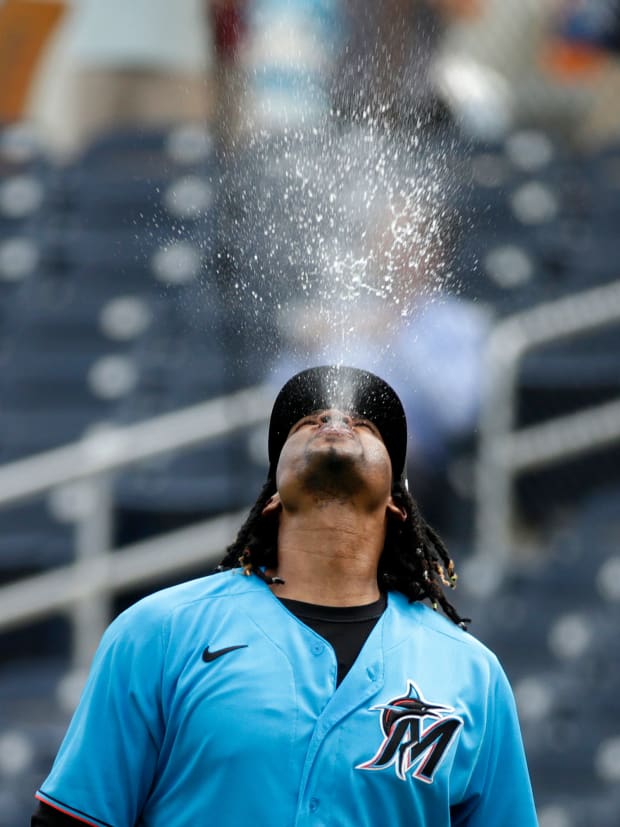

If MLB, gets its way, player behavior will have to change significantly in a 2020 season. That means no spitting.

Rockies right fielder Charlie Blackmon read through MLB’s

proposed health and safety regulations last week and immediately began planning a trip to the hardware store.In an attempt to prevent the spread of the virus, the league’s 67-page memo, which players received last Friday, suggested banning the use of such petri dishes as shared showers and hot and cold tubs. That’s fine, says Blackmon, who is renowned among Colorado staffers for his pre- and postgame routines. These include at least one session in the cold tub per day.

His solution, he says: “I’m gonna go to Home Depot and get a 50-gallon rubber trash can and just go put it in the auxiliary closet and dump a bunch of ice and a hose in it.”

There are much more serious concerns as the U.S. closes in on 100,000 deaths from the coronavirus. But as MLB attempts to forge a path forward, it faces an elemental problem: Baseball is fundamentally unsuited to cleanliness.

Consider a typical play: The hitter, who has spent the afternoon sharing tubs and showers with his teammates, approaches the plate. He may spit on his hands or rub dirt on them to improve his grip on the bat he has already coated with pine tar. He spits tobacco juice onto the ground, inches from the catcher and umpire. Sixty feet, six inches away, the pitcher dabs at the pine tar subtly applied to his cap, then mixes it with the sunscreen and sweat on his forearm and a little rosin from the bag every other pitcher on both teams will touch. Finding the ball still too dry, he licks his hands, then massages it. The hitter singles. The ball rolls around in the grass until an outfielder throws it in. The runner on third has scored. Every member of his team congratulates him with a high five. This is an epidemiologist’s worst nightmare.

Still, give MLB credit for trying. The league’s proposal includes such provisions as the ban on shared tubs. It calls for players to shower at home or at the hotel. (“Hats off to the teams playing in Atlanta in August,” tweeted Brewers lefty Brett Anderson.) It encourages teams to use every other locker and to set up extra clubhouses to encourage social distancing. It limits the number of trainers to two and suggests that teams limit the number of players in the training and weight rooms. It mandates the washing of hands between innings. (Of the legendarily grimy dugout bathrooms, Braves righty Josh Tomlin says with a laugh, “I think you’re putting yourself more at risk touching the doorknob.”) It outlaws sunflower seeds and chewing tobacco, and the resulting spitting. It bans high fives. (Nationals reliever Daniel Hudson preemptively mourns the first time he saves a game and he and the catcher begin to run toward one another before remembering.)

The players are mixed in their reaction to the proposal, but most seem to agree with Blackmon, who says that some of the details bother him, “but at the same time, I’m not going to be stubborn and not adapt and make a big stink of it such that we miss out on games because of my personal feelings.”

Most players’ major worries stem from their well-being and that of their loved ones. Nationals reliever Sean Doolittle’s wife, Eireann Dolan, has a history of respiratory issues, and he has expressed concern that his participation in the season might expose her to danger. Tomlin says his wife and three young children will stay home in Tyler, Tx., rather than accompany him to ballparks. Hudson says he fears the team trainers, tasked with administering COVID testing, will be at high risk of contracting the disease. In a statement, an MLB spokesman said, “Amid significant uncertainty, the unpredictability of COVID-19 and evolving state and local orders, our paramount concern remains clear: the health and safety of our players, employees, fans and the public at large.”

And then there are the typical concerns of an athlete embarking on a season. “They talk about health and safety with the virus,” Cardinals reliever Andrew Miller says. “But what about our health and safety as players?”

Miller missed more than three months in 2018 because of injuries to his left hamstring, right knee and left shoulder. He turned 35 last week. He tries to arrive at the ballpark early each day, which will become more difficult if the league succeeds at encouraging players to use only team buses. (Miller is on board with that one, though. “I don’t think I’ll be taking the 4 train to Yankee Stadium anyway,” he says.) When he gets there, he begins an extended pregame routine designed to keep him in game shape.

No one seems to think two trainers are enough or that the staggered trips to the weight room will provide ample time for each player. The Nationals, Hudson points out, were the oldest team in baseball last year, with an average age of 30.9. They need all the help they can get when it comes to maintaining their bodies, which generally means time working with trainers as well as time on their own stretching. In the weight room before a game, Hudson says, “There’s more guys in there getting ready to take BP than there are guys working out.”

Still, these concerns seem manageable. Maybe you increase the number of trainers and set up outdoor weight areas. And most of the rest are minor, right? Like no spitting?

“Wait, what?” Blackmon says. “I’m 100% gonna spit. That’s ingrained in my playing the game. Whether or not I’m dipping or chewing gum, I’m still gonna spit. I have to occupy my mind. It’s like putting things on autopilot. You see it like with Hunter Pence, where he would constantly be adjusting his uniform. I don’t have this idle time where my consciousness wanders. I fill my time with thought processes that are like a cruise control.”

Tomlin is with him there. It’s “probably not” physically possible for him to play baseball without spitting, he says. He is addicted to tobacco, but even if he switches to a nicotine patch or starts lighting cigarettes behind the dugout, he will not be able to stop spitting, because he all but blacks out on the mound.

“If I’m spitting, I don’t remember spitting,” he says. If I pick up dirt and wipe it on the ball, I don’t think about doing it before I do it. It just happens. Hell, I do it playing catch sometimes!”

So if we do have a 2020 baseball season—if the league and the players association can hammer out an agreement when it comes to the money, if the league can secure enough testing to ensure the participants’ safety, if local governments allow them to begin play—there will likely be some compromise. Blackmon will eschew the public cold tub and instead climb into his trash can. Between pitches, he’ll spit. And between innings, he’ll wash his hands.

If MLB, gets its way, player behavior will have to change significantly in a 2020 season. That means no spitting.

Rockies right fielder Charlie Blackmon read through MLB’s proposed health and safety regulations last week and immediately began planning a trip to the hardware store.

In an attempt to prevent the spread of the virus, the league’s 67-page memo, which players received last Friday, suggested banning the use of such petri dishes as shared showers and hot and cold tubs. That’s fine, says Blackmon, who is renowned among Colorado staffers for his pre- and postgame routines. These include at least one session in the cold tub per day.

His solution, he says: “I’m gonna go to Home Depot and get a 50-gallon rubber trash can and just go put it in the auxiliary closet and dump a bunch of ice and a hose in it.”

There are much more serious concerns as the U.S. closes in on 100,000 deaths from the coronavirus. But as MLB attempts to forge a path forward, it faces an elemental problem: Baseball is fundamentally unsuited to cleanliness.

Consider a typical play: The hitter, who has spent the afternoon sharing tubs and showers with his teammates, approaches the plate. He may spit on his hands or rub dirt on them to improve his grip on the bat he has already coated with pine tar. He spits tobacco juice onto the ground, inches from the catcher and umpire. Sixty feet, six inches away, the pitcher dabs at the pine tar subtly applied to his cap, then mixes it with the sunscreen and sweat on his forearm and a little rosin from the bag every other pitcher on both teams will touch. Finding the ball still too dry, he licks his hands, then massages it. The hitter singles. The ball rolls around in the grass until an outfielder throws it in. The runner on third has scored. Every member of his team congratulates him with a high five. This is an epidemiologist’s worst nightmare.

Still, give MLB credit for trying. The league’s proposal includes such provisions as the ban on shared tubs. It calls for players to shower at home or at the hotel. (“Hats off to the teams playing in Atlanta in August,” tweeted Brewers lefty Brett Anderson.) It encourages teams to use every other locker and to set up extra clubhouses to encourage social distancing. It limits the number of trainers to two and suggests that teams limit the number of players in the training and weight rooms. It mandates the washing of hands between innings. (Of the legendarily grimy dugout bathrooms, Braves righty Josh Tomlin says with a laugh, “I think you’re putting yourself more at risk touching the doorknob.”) It outlaws sunflower seeds and chewing tobacco, and the resulting spitting. It bans high fives. (Nationals reliever Daniel Hudson preemptively mourns the first time he saves a game and he and the catcher begin to run toward one another before remembering.)

The players are mixed in their reaction to the proposal, but most seem to agree with Blackmon, who says that some of the details bother him, “but at the same time, I’m not going to be stubborn and not adapt and make a big stink of it such that we miss out on games because of my personal feelings.”

Most players’ major worries stem from their well-being and that of their loved ones. Nationals reliever Sean Doolittle’s wife, Eireann Dolan, has a history of respiratory issues, and he has expressed concern that his participation in the season might expose her to danger. Tomlin says his wife and three young children will stay home in Tyler, Tx., rather than accompany him to ballparks. Hudson says he fears the team trainers, tasked with administering COVID testing, will be at high risk of contracting the disease. In a statement, an MLB spokesman said, “Amid significant uncertainty, the unpredictability of COVID-19 and evolving state and local orders, our paramount concern remains clear: the health and safety of our players, employees, fans and the public at large.”

And then there are the typical concerns of an athlete embarking on a season. “They talk about health and safety with the virus,” Cardinals reliever Andrew Miller says. “But what about our health and safety as players?”

Miller missed more than three months in 2018 because of injuries to his left hamstring, right knee and left shoulder. He turned 35 last week. He tries to arrive at the ballpark early each day, which will become more difficult if the league succeeds at encouraging players to use only team buses. (Miller is on board with that one, though. “I don’t think I’ll be taking the 4 train to Yankee Stadium anyway,” he says.) When he gets there, he begins an extended pregame routine designed to keep him in game shape.

No one seems to think two trainers are enough or that the staggered trips to the weight room will provide ample time for each player. The Nationals, Hudson points out, were the oldest team in baseball last year, with an average age of 30.9. They need all the help they can get when it comes to maintaining their bodies, which generally means time working with trainers as well as time on their own stretching. In the weight room before a game, Hudson says, “There’s more guys in there getting ready to take BP than there are guys working out.”

Still, these concerns seem manageable. Maybe you increase the number of trainers and set up outdoor weight areas. And most of the rest are minor, right? Like no spitting?

“Wait, what?” Blackmon says. “I’m 100% gonna spit. That’s ingrained in my playing the game. Whether or not I’m dipping or chewing gum, I’m still gonna spit. I have to occupy my mind. It’s like putting things on autopilot. You see it like with Hunter Pence, where he would constantly be adjusting his uniform. I don’t have this idle time where my consciousness wanders. I fill my time with thought processes that are like a cruise control.”

Tomlin is with him there. It’s “probably not” physically possible for him to play baseball without spitting, he says. He is addicted to tobacco, but even if he switches to a nicotine patch or starts lighting cigarettes behind the dugout, he will not be able to stop spitting, because he all but blacks out on the mound.

“If I’m spitting, I don’t remember spitting,” he says. If I pick up dirt and wipe it on the ball, I don’t think about doing it before I do it. It just happens. Hell, I do it playing catch sometimes!”

So if we do have a 2020 baseball season—if the league and the players association can hammer out an agreement when it comes to the money, if the league can secure enough testing to ensure the participants’ safety, if local governments allow them to begin play—there will likely be some compromise. Blackmon will eschew the public cold tub and instead climb into his trash can. Between pitches, he’ll spit. And between innings, he’ll wash his hands.

0 Comments