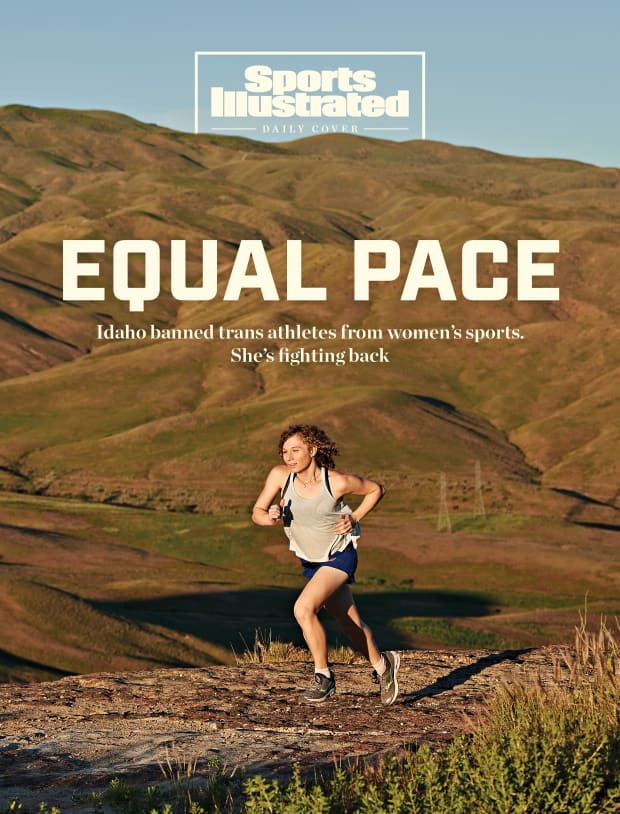

Lindsay Hecox sued the state for the right to compete—putting the Boise State student on the leading edge of the battle for transgender rights.

Every night around 7 or 8, Lindsay Hecox goes for a run. As she jogs along the winding, 25-mile Greenbelt path through Boise, her tight blond curls bobbing, she sometimes waves to a group of women, also running.

They’ve never met, but the women often return her eye contact. Some smile.

“I just recognize the fact that they know, based on their facial expression. This is sort of awkward because I know some of them by face and don’t really know anything about them, like name or personality,” she says. “But they know a lot about me.”

Hecox is running past the Boise State women’s cross-country team, the group she’s fighting hard to be able to join when she starts her sophomore year this fall (assuming all goes according to plan with the school’s reopening). As a transgender woman, Hecox, 19, will soon be barred by Idaho from participating in women’s sports in the state, even though NCAA rules allow it.

On March 30, the eve of the International Transgender Day of Visibility, Republican Governor Brad Little signed the ban—the first of its kind nationwide—into law. Girls and women who compete in youth, high school and college sports, whether they’re transgender or cisgender, will be subject to being challenged by competitors on their biological sex—in essence, forced to prove their womanhood. If found to not be “female,” they would not be able to compete with girls and women.

The law states that athletes can verify their sex in one of three ways: They could get a test confirming that their natural hormone levels fall within a certain range. They could get a genetic test, confirming XX chromosomes. Finally, they could undergo a physical exam by a doctor to confirm they have female genitals. Advocates say that the law forces athletes into the position of having to drop their pants to compete, since routine physicals to clear athletes for athletic participation don’t include a genital exam or sufficient questions to determine biological sex. (Supporters of the law claim they do.)

Such invasive policies affect not only trans, nonbinary and intersex athletes, but also cisgender girls and women who may be particularly big, muscular, or otherwise dominant.

In April, Hecox sued the state of Idaho, teaming with a Jane Doe, the American Civil Liberties Union and the northwestern feminist organization Legal Voice, to challenge its so-called

Fairness in Women’s Sports Act, which is set to go into effect July 1. Jane Doe is a 17-year-old incoming Boise High School senior who plays soccer and runs track. She is cisgender, not transgender, but is suing because she fears her privacy will be at stake if one of her competitors wants to dispute her sex. The state has not yet set up a formal system for lodging these types of challenges, but in the meantime, it’s as simple as contacting the school.While Doe has remained anonymous, Hecox has been publicly outspoken, emerging as the face of the challenge to the law—and placing her on the leading edge of the fight for trans rights in Idaho, and, by extension, the United States.

Across the country, 16 state legislatures have introduced bills similar to Idaho’s that would restrict trans women and girls from competing in sports aligned with their gender identity as opposed to their biological sex. (Meanwhile, a lawsuit is playing out in Connecticut that challenges the state’s policy of allowing transgender athletes to participate, no questions asked.)

The wave of legislation, none of which has so far passed, save for Idaho’s, follows last decade’s wave of so-called “bathroom bills,” in which legislators from at least 24 states sought to limit which restrooms and locker rooms trans people could use to those that matched their sex assigned at birth, not their current gender identity. While only one of those states, North Carolina, passed such a bill into law, and it was repealed in 2017, “bathroom bills” were seized on by politicians nationwide—and talking heads on cables news and radio—as a potent wedge issue. Now, sports are the next frontier.

“In the past, our opponents have really been pushing anti-trans laws in the form of banning trans people being able to use restrooms that match their gender identity,” says Gabriel Arkles, an ACLU senior staff attorney. “And now they’re switching tactics, and they’ve decided trans people are more vulnerable if they target us with the angle of sports.”

Activists and experts fear that discriminating against trans people in sports would serve as an entry point to denying them more basic rights outside of recreation—essentially, providing a high-profile way to define transgender people as different and “other.” Meanwhile, at least one study has shown that accepting transgender athletes in sports reduces stereotypes and discrimination in other arenas.

“I firmly believe that sport is a vehicle for social change,” says Chris Mosier, a Team USA duathlete and activist who is transgender. “And so the reason this lawsuit is so important and that it’s happening through sport is so important [is that] what happens here will ultimately influence how policies come down in terms of housing discrimination, employment discrimination, adoption cases, and discrimination suits across the board.”

On June 15, the fight over transgender athletes’ rights received an unexpected jolt: the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County, which found that, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, queer and transgender people cannot be fired from their jobs solely based on their gender identity or sexual orientation. Advocates argue that the same trans-inclusive definition of sex discrimination should also apply to Title IX, the 1972 federal civil rights law that prevents discrimination in education, including sports. Backers of the Idaho law say the opposite.

“I think that [the SCOTUS decision provides] a lot of momentum to people who want to use civil rights laws to challenge policies that are excluding transgender kids from sports,” says Erin Buzuvis, a Western New England University law professor who specializes in gender and discrimination in athletics. “Absolutely those cases are on much stronger footing now than they would be if the court decision had come out the other way or even if the court had just stayed silent.”

Hecox knows, though, that the ultimate effect of the Supreme Court ruling is uncertain—and that winning her suit, and the right to participate in her sport, is far from assured. Whatever the outcome, she also knows the fight will be difficult. “I usually am very optimistic,” she says, “but in this specific instance involving this lawsuit, I think I tend to overestimate how many people are against me.”

***

Lindsay Hecox began running early. First, as a shy middle schooler in Moorpark, Calif., when she still presented as male, she excelled in PE at the Pacer Test most students dread—a 20-meter shuttle run, hustling from side to side between obnoxiously loud chimes that squeeze closer and closer together. “She made it a race against herself,” says her mother, Monica.

She kept at it. And though she had an inkling at age nine or 10 that she might be trans, she wasn’t sure, and she told no one and presented as male 24/7 through high school. Classwork, cross-country and track kept her busy —her senior year, she made it to the California Interscholastic Federation finals in the 1600—so she let the question of her gender slip to the back of her mind—until she couldn’t any longer. “I was not a boy, but I had to pretend to be one, which is unexplainably hard, to not be who you really are.”

Hecox can still rattle off her PRs in cross-country, the 800 meters, 1600 and 3200, but sometimes feels uncomfortable sharing that she once could, for example, run a mile in 4:51, since that reflects a time she can likely no longer hit, now that her hormone structure has changed. “I just want to run at whatever level I’m at,” Hecox says. “But I always have the fear that if I run too fast, it’s going to be a problem.”

As she completed her senior year of high school, she worried she might fail a difficult AP Statistics course. She felt like the class, and all its stress, was the last thing preventing her from focusing on herself. When she did finally pass, she gave herself the freedom to look inward. She’d spent half a lifetime questioning her gender—the thought frequently popping up, but then always being shunted away as she turned her focus to something else.

Now, a music buff (Pink Floyd, Rush, Zeppelin), she found herself listening to Against Me!’s aptly named “Transgender Dysphoria Blues” on repeat. (Sample line: “You want them to see you like they see every other girl.”) “I am transgender,” she told herself on May 8, 2019, and she instantly knew it was true. “Something in me snapped,” Hecox says. “It wasn’t liking wearing girls’ clothes—it was wearing girls’ clothes because I am a girl.”

Free of high school’s constraints, Hecox came out to family and a couple of friends, and began transitioning as she prepared to study psychology at Boise State (dream job: gender therapist). She always knew she didn’t want to run her freshman year—and, now that she came out, she couldn’t have anyway, under NCAA rules, which require a year of hormone-suppression treatment—to give her time to adjust to college life. Now she’s ready, but on Feb. 13, she learned Idaho wasn’t ready for her.

That was the date that state Representative Barbara Ehardt, a Republican, introduced HB500 to the House.

“I was a little bit in shock like, ‘Woah, I can’t believe this is actually happening to me,’ ” Hecox says. “There definitely was a level of ‘Come on, really, are you seriously going to police this?’ I wasn’t angry when I started hearing about this. It was just disbelief and apprehension as to why this was such an important thing for politicians to do.”

Day after day, she showed up to the statehouse for rallies, testimony and other community organizing. By the time the bill was signed into law by Little—along with another anti-trans bill—other state legislatures had already shut down due to the coronavirus.

Hecox never imagined herself being an activist, and neither did her mother. But even as she experienced depression brought on by the legislation, she threw herself into that role this winter: Hecox knew she wanted to be the face of the lawsuit.

“It’s not about taking spots away from girls,” Hecox says. “It’s not about being at an advantage. It’s not about beating other schools easier. I literally just love the sport and I don’t care if I’m in last place or first place.”

Hecox’s presence on the ground in Idaho has been vital to organizing against the new law, says Chelsea Gaona-Lincoln, a Legal Voice litigation support coordinator based in the state.

“She did such a great job and was really a light at the Capitol,” Gaona-Lincoln says. “That kind of spirit and the dynamics of her personality at such a young age are definitely a good reminder of why people like me are still into this work and still trying to do this work. It definitely gives you a feeling of hope, even living in a state like Idaho.”

***

Barbara Ehardt started working on HB500 in 2018, hoping to introduce it during the 2019 legislative session, but after four drafts, she still couldn’t get the wording right. So she linked up with the Alliance Defending Freedom, a Christian nonprofit that Vox has called “the one-stop legal shop for nearly every anti-trans lawsuit in the US,” to craft the bill.

A former Idaho State point guard and coach at four Division I women’s basketball programs, Ehardt says her law is protecting cisgender girls and women from what she sees as more difficult competition. “It’s important to me because Title IX changed my life, and I know from absolute personal experiences both in competing and in coaching in all facets of the game as women, as girls, that we cannot compete against the inherent physiological and scientifically proven advantages that biological males present, regardless of hormone usage,” she says, referring to transgender women as “biological males.”

In May, the month after Hecox sued Idaho, the ADF filed a motion to intervene on behalf of two cisgender cross-country runners at Idaho State who believe transgender women have an unfair advantage. And in June, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a statement of interest in the case, siding with the state.

“I want to be up there winning races and podiuming,” says Madison Kenyon, an incoming sophomore at Idaho State University who, aligned with ADF, is looking to join the ongoing Hecox v. Little litigation. If a judge allows the intervention, the cisgender women would be allowed to participate in a hearing. Kenyon has competed against trans women in both high school and college. “I’m seeing girls right now in the place that I want to be at getting bumped off the podium,” she says, “and losing those opportunities of success because they’re losing to biological males.”

The question of who gets to be seen as a woman in athletic competition is not new. For two years in the '60s, women had to stand naked to verify their sex for international sports officials. Later, chromosome testing—a flawed metric, since not all women are born with XX chromosomes—was used. This century, South African runner Caster Semenya has endured mandatory sex verification testing and unending scrutiny by the International Association of Athletics Federations, following her victory in the 800 meters at the World Championships in Athletics in 2009. She was cleared the next year to continue competing as a woman, only to find that in 2018, the IAAF passed new a rule that barred her due to her high testosterone level.

At lower levels of sports, excluding trans athletes by prioritizing competitive balance over education and inclusion can have powerful consequences. Transgender teens have higher rates of suicidal ideation, plans and attempts than their cisgender peers, as well as higher rates of nonsuicidal self-injury. Gender discrimination and isolation are among the common reasons for suicide among trans people. While Ehardt argues that trans girls and women would be free to compete on boys’ and men’s teams, it’s a humiliating prospect that would do little to ease competitors’ gender dysphoria.

While supporters of the Idaho law argue that cisgender girls and women would be at a disadvantage against transgender competitors, the science remains unsettled. It’s known that people with testosterone-dominant bodies recover more quickly from physical activity than their estrogen-dominant counterparts, which leads to more muscle growth. One landmark study has shown that adult trans women experienced a statistically significant decrease in muscle mass after one year of testosterone suppression and cross-hormone therapy, though not nearly enough to put them on a level playing field with cisgender women. But those findings were from a small sample of nonathletes, and also cannot easily be applied to kids who are still undergoing puberty. There’s almost no research that’s been done on trans athletes, let alone young ones; it’s something that Joanna Harper, a Loughborough University Ph.D. student researching performance analysis in trans athletes, is working to address.

“What needs to happen over the next 10 to 12 years is we need to get some trans athletes into exercise labs,” says Harper, who has also advised the International Olympic Committee on its transgender-related policies. She points out that regardless of being transgender or cisgender, athletes have all kinds of advantages over each other: size, strength, skill, speed and endurance among them. As a trans runner herself, Harper noted that within weeks of beginning treatment, she was running more slowly, likely due to a lower red blood cell count, which affects how much oxygen the blood can take in from the lungs.

The idea that cisgender women need to be saved from stiff athletic competition is “a really dangerous road to go down because it just invokes all the stereotypes that we’re trying to get away from that girls and women need protecting in the first place,” says Heath Fogg Davis, the director of Temple University’s gender, sexuality, and women’s studies program.

Buzuvis, from Western New England University, agrees: “I think that if we weren’t so obsessed with promoting the idea of female athletic inferiority, we might actually discover that female athletes are better than we ever thought they were.”

In Connecticut, the other main battleground for trans rights in sports, one of the three cisgender girls who filed a federal lawsuit against transgender runners Andraya Yearwood and Terry Miller, backed by the ADF, actually ended up beating Miller days later in a 55-meter dash.

Like 17 other states, Connecticut currently allows transgender student-athletes to compete on the teams aligning with their gender identity. Twenty-six other states restrict trans participation either based on a birth certificate or on a case-by-case basis. As the lawsuit in Connecticut, which seeks to restrict transgender participation, works its way through the courts, trans athletes there can still compete—making Idaho the only state with a ban.

The NCAA and IOC take steps to regulate trans participation, but neither is nearly as aggressive as Idaho’s policy. A trans man, the NCAA says, may compete on the men’s team, no strings attached. A trans woman can compete on the women’s team after a year of hormone-suppression treatment. Meanwhile, in 2015, the IOC established that trans men may compete in men’s sports, and trans women in women’s sports, provided their testosterone levels stayed below 10 nanomoles per liter of blood for one year.

“When you have a high school athletic association that should be on the most inclusive end of the spectrum leapfrogging over all the other sport organizations in terms of making their policies the most restrictive, even more restrictive than the policies we’re seeing governed at the Olympic level, it’s just completely out of sync with what’s appropriate and what kind of values should be reflected in their policy,” Buzuvis says.

In fact, for its part, the NCAA is likely to protest Idaho’s ban by moving any championship games out of state, including first- and second-round games of the 2021 men’s basketball tournament. “Idaho’s House Bill 500 and resulting law is harmful to transgender student-athletes and conflicts with the NCAA’s core values of inclusivity, respect and the equitable treatment of all individuals,” it said in a June 11 statement. They’ll discuss the issue at an August Board of Governors meeting.

The NCAA’s statement came in response to a letter calling on the association to pull out from hosting any championship games in Idaho while the law remains in effect. Signees included professional, Olympic and Paralympic athletes, among them tennis legend Billie Jean King, USWNT star Megan Rapinoe, longtime Storm and Team USA point guard Sue Bird, and Knicks shooting guard Reggie Bullock, along with 500-plus student-athletes and advocacy organizations like Athlete Ally, a nonprofit dedicated to ending homophobia and transphobia in sports. In 2016, the NCAA moved events, including its basketball tournament matchups, out of North Carolina in light of the state’s bathroom bill, ending its prohibition only once state legislators repealed the law the following year.

“Obviously, if my sister was here and she wanted to play a sport, I don’t think what she classified herself as should be used against her,” says Bullock, an Athlete Ally ambassador whose late sister Mia Henderson was transgender. “It’s disrespectful to me in pretty much every way.”

King, arguably the main face of gender equality in all of sports, says in an email: “I’ve spent most of my life working for equality for all. Sport has given me an incredible platform because sports are a microcosm of society and can be used as a catalyst for social change. Everyone should be treated equally.”

***

While the Supreme Court made it clear that sex discrimination includes discrimination against transgender individuals, Hecox’s legal team will still have to prove that banning transgender girls and women from sports teams constitutes discrimination.

Some lower courts will begin applying the landmark ruling to other cases of discrimination right away, though some conservative judges may resist, says Jami Taylor, a University of Toledo political science professor who specializes in transgender issues. Multiple Title IX cases related to trans athletes could end up bouncing around circuit courts with different decisions—which is a recipe for one of them, though not necessarily Hecox’s, reaching the nation’s highest court. “I do think that case or a similar Title IX case is going to end up before the Supreme Court,” Taylor says in an email. She predicts that the court will allow trans participation, but with caveats—like those instituted by the NCAA and IOC to regulate trans female testosterone levels—and not the blanket inclusion that the court allowed with employment nondiscrimination.

Some experts, like Taylor, believe that a carve-out for transgender women and girls in the form of a testosterone requirement is reasonable to ensure they’re on a level playing field with their cisgender counterparts. Others, like Buzuvis, would like to see blanket inclusion. Still more, like Davis, would like to see gender-segregated sports end entirely in favor of the inclusion of all genders in any particular arena, though that is a more radical view. The range of opinions points to the complexity of the issue.

The outcome of Hecox v Little could also rest, in part, on public opinion, and people remain very divided on this issue—much more divided, Taylor says, than on workplace discrimination, where the Supreme Court essentially ratified a national consensus. “Does the court go look at public opinion polls and stick a finger in the wind? No,” she says. “But is the court part of the society it lives in?”

According to a January 2020 study published in the journal Sex Roles by Taylor and other researchers, the society it lives in isn’t sold: Just 35.6% of women and 23.2% of men believe trans athletes should participate in sports aligned with their gender identity.

“This really challenges people on a deep, deep level because it takes away a very deeply entrenched tradition that’s very much a part of our culture,” Davis says.

This is, in part, why Hecox believes it’s so important to share her story. She wants to put a human face on the issue, so that everyone can see that all she wants is to run.

“I don’t want to be just that one trans girl,” she says. “I want to be the runner who is really dedicated to the sport and tries her best every single day.”

Lindsay Hecox sued the state for the right to compete—putting the Boise State student on the leading edge of the battle for transgender rights.

Every night around 7 or 8, Lindsay Hecox goes for a run. As she jogs along the winding, 25-mile Greenbelt path through Boise, her tight blond curls bobbing, she sometimes waves to a group of women, also running.

They’ve never met, but the women often return her eye contact. Some smile.

“I just recognize the fact that they know, based on their facial expression. This is sort of awkward because I know some of them by face and don’t really know anything about them, like name or personality,” she says. “But they know a lot about me.”

Hecox is running past the Boise State women’s cross-country team, the group she’s fighting hard to be able to join when she starts her sophomore year this fall (assuming all goes according to plan with the school’s reopening). As a transgender woman, Hecox, 19, will soon be barred by Idaho from participating in women’s sports in the state, even though NCAA rules allow it.

On March 30, the eve of the International Transgender Day of Visibility, Republican Governor Brad Little signed the ban—the first of its kind nationwide—into law. Girls and women who compete in youth, high school and college sports, whether they’re transgender or cisgender, will be subject to being challenged by competitors on their biological sex—in essence, forced to prove their womanhood. If found to not be “female,” they would not be able to compete with girls and women.

The law states that athletes can verify their sex in one of three ways: They could get a test confirming that their natural hormone levels fall within a certain range. They could get a genetic test, confirming XX chromosomes. Finally, they could undergo a physical exam by a doctor to confirm they have female genitals. Advocates say that the law forces athletes into the position of having to drop their pants to compete, since routine physicals to clear athletes for athletic participation don’t include a genital exam or sufficient questions to determine biological sex. (Supporters of the law claim they do.)

Such invasive policies affect not only trans, nonbinary and intersex athletes, but also cisgender girls and women who may be particularly big, muscular, or otherwise dominant.

In April, Hecox sued the state of Idaho, teaming with a Jane Doe, the American Civil Liberties Union and the northwestern feminist organization Legal Voice, to challenge its so-called Fairness in Women’s Sports Act, which is set to go into effect July 1. Jane Doe is a 17-year-old incoming Boise High School senior who plays soccer and runs track. She is cisgender, not transgender, but is suing because she fears her privacy will be at stake if one of her competitors wants to dispute her sex. The state has not yet set up a formal system for lodging these types of challenges, but in the meantime, it’s as simple as contacting the school.

While Doe has remained anonymous, Hecox has been publicly outspoken, emerging as the face of the challenge to the law—and placing her on the leading edge of the fight for trans rights in Idaho, and, by extension, the United States.

Across the country, 16 state legislatures have introduced bills similar to Idaho’s that would restrict trans women and girls from competing in sports aligned with their gender identity as opposed to their biological sex. (Meanwhile, a lawsuit is playing out in Connecticut that challenges the state’s policy of allowing transgender athletes to participate, no questions asked.)

The wave of legislation, none of which has so far passed, save for Idaho’s, follows last decade’s wave of so-called “bathroom bills,” in which legislators from at least 24 states sought to limit which restrooms and locker rooms trans people could use to those that matched their sex assigned at birth, not their current gender identity. While only one of those states, North Carolina, passed such a bill into law, and it was repealed in 2017, “bathroom bills” were seized on by politicians nationwide—and talking heads on cables news and radio—as a potent wedge issue. Now, sports are the next frontier.

“In the past, our opponents have really been pushing anti-trans laws in the form of banning trans people being able to use restrooms that match their gender identity,” says Gabriel Arkles, an ACLU senior staff attorney. “And now they’re switching tactics, and they’ve decided trans people are more vulnerable if they target us with the angle of sports.”

Activists and experts fear that discriminating against trans people in sports would serve as an entry point to denying them more basic rights outside of recreation—essentially, providing a high-profile way to define transgender people as different and “other.” Meanwhile, at least one study has shown that accepting transgender athletes in sports reduces stereotypes and discrimination in other arenas.

“I firmly believe that sport is a vehicle for social change,” says Chris Mosier, a Team USA duathlete and activist who is transgender. “And so the reason this lawsuit is so important and that it’s happening through sport is so important [is that] what happens here will ultimately influence how policies come down in terms of housing discrimination, employment discrimination, adoption cases, and discrimination suits across the board.”

On June 15, the fight over transgender athletes’ rights received an unexpected jolt: the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County, which found that, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, queer and transgender people cannot be fired from their jobs solely based on their gender identity or sexual orientation. Advocates argue that the same trans-inclusive definition of sex discrimination should also apply to Title IX, the 1972 federal civil rights law that prevents discrimination in education, including sports. Backers of the Idaho law say the opposite.

“I think that [the SCOTUS decision provides] a lot of momentum to people who want to use civil rights laws to challenge policies that are excluding transgender kids from sports,” says Erin Buzuvis, a Western New England University law professor who specializes in gender and discrimination in athletics. “Absolutely those cases are on much stronger footing now than they would be if the court decision had come out the other way or even if the court had just stayed silent.”

Hecox knows, though, that the ultimate effect of the Supreme Court ruling is uncertain—and that winning her suit, and the right to participate in her sport, is far from assured. Whatever the outcome, she also knows the fight will be difficult. “I usually am very optimistic,” she says, “but in this specific instance involving this lawsuit, I think I tend to overestimate how many people are against me.”

***

Lindsay Hecox began running early. First, as a shy middle schooler in Moorpark, Calif., when she still presented as male, she excelled in PE at the Pacer Test most students dread—a 20-meter shuttle run, hustling from side to side between obnoxiously loud chimes that squeeze closer and closer together. “She made it a race against herself,” says her mother, Monica.

She kept at it. And though she had an inkling at age nine or 10 that she might be trans, she wasn’t sure, and she told no one and presented as male 24/7 through high school. Classwork, cross-country and track kept her busy —her senior year, she made it to the California Interscholastic Federation finals in the 1600—so she let the question of her gender slip to the back of her mind—until she couldn’t any longer. “I was not a boy, but I had to pretend to be one, which is unexplainably hard, to not be who you really are.”

Hecox can still rattle off her PRs in cross-country, the 800 meters, 1600 and 3200, but sometimes feels uncomfortable sharing that she once could, for example, run a mile in 4:51, since that reflects a time she can likely no longer hit, now that her hormone structure has changed. “I just want to run at whatever level I’m at,” Hecox says. “But I always have the fear that if I run too fast, it’s going to be a problem.”

As she completed her senior year of high school, she worried she might fail a difficult AP Statistics course. She felt like the class, and all its stress, was the last thing preventing her from focusing on herself. When she did finally pass, she gave herself the freedom to look inward. She’d spent half a lifetime questioning her gender—the thought frequently popping up, but then always being shunted away as she turned her focus to something else.

Now, a music buff (Pink Floyd, Rush, Zeppelin), she found herself listening to Against Me!’s aptly named “Transgender Dysphoria Blues” on repeat. (Sample line: “You want them to see you like they see every other girl.”) “I am transgender,” she told herself on May 8, 2019, and she instantly knew it was true. “Something in me snapped,” Hecox says. “It wasn’t liking wearing girls’ clothes—it was wearing girls’ clothes because I am a girl.”

Free of high school’s constraints, Hecox came out to family and a couple of friends, and began transitioning as she prepared to study psychology at Boise State (dream job: gender therapist). She always knew she didn’t want to run her freshman year—and, now that she came out, she couldn’t have anyway, under NCAA rules, which require a year of hormone-suppression treatment—to give her time to adjust to college life. Now she’s ready, but on Feb. 13, she learned Idaho wasn’t ready for her.

That was the date that state Representative Barbara Ehardt, a Republican, introduced HB500 to the House.

“I was a little bit in shock like, ‘Woah, I can’t believe this is actually happening to me,’ ” Hecox says. “There definitely was a level of ‘Come on, really, are you seriously going to police this?’ I wasn’t angry when I started hearing about this. It was just disbelief and apprehension as to why this was such an important thing for politicians to do.”

Day after day, she showed up to the statehouse for rallies, testimony and other community organizing. By the time the bill was signed into law by Little—along with another anti-trans bill—other state legislatures had already shut down due to the coronavirus.

Hecox never imagined herself being an activist, and neither did her mother. But even as she experienced depression brought on by the legislation, she threw herself into that role this winter: Hecox knew she wanted to be the face of the lawsuit.

“It’s not about taking spots away from girls,” Hecox says. “It’s not about being at an advantage. It’s not about beating other schools easier. I literally just love the sport and I don’t care if I’m in last place or first place.”

Hecox’s presence on the ground in Idaho has been vital to organizing against the new law, says Chelsea Gaona-Lincoln, a Legal Voice litigation support coordinator based in the state.

“She did such a great job and was really a light at the Capitol,” Gaona-Lincoln says. “That kind of spirit and the dynamics of her personality at such a young age are definitely a good reminder of why people like me are still into this work and still trying to do this work. It definitely gives you a feeling of hope, even living in a state like Idaho.”

***

Barbara Ehardt started working on HB500 in 2018, hoping to introduce it during the 2019 legislative session, but after four drafts, she still couldn’t get the wording right. So she linked up with the Alliance Defending Freedom, a Christian nonprofit that Vox has called “the one-stop legal shop for nearly every anti-trans lawsuit in the US,” to craft the bill.

A former Idaho State point guard and coach at four Division I women’s basketball programs, Ehardt says her law is protecting cisgender girls and women from what she sees as more difficult competition. “It’s important to me because Title IX changed my life, and I know from absolute personal experiences both in competing and in coaching in all facets of the game as women, as girls, that we cannot compete against the inherent physiological and scientifically proven advantages that biological males present, regardless of hormone usage,” she says, referring to transgender women as “biological males.”

In May, the month after Hecox sued Idaho, the ADF filed a motion to intervene on behalf of two cisgender cross-country runners at Idaho State who believe transgender women have an unfair advantage. And in June, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a statement of interest in the case, siding with the state.

“I want to be up there winning races and podiuming,” says Madison Kenyon, an incoming sophomore at Idaho State University who, aligned with ADF, is looking to join the ongoing Hecox v. Little litigation. If a judge allows the intervention, the cisgender women would be allowed to participate in a hearing. Kenyon has competed against trans women in both high school and college. “I’m seeing girls right now in the place that I want to be at getting bumped off the podium,” she says, “and losing those opportunities of success because they’re losing to biological males.”

The question of who gets to be seen as a woman in athletic competition is not new. For two years in the '60s, women had to stand naked to verify their sex for international sports officials. Later, chromosome testing—a flawed metric, since not all women are born with XX chromosomes—was used. This century, South African runner Caster Semenya has endured mandatory sex verification testing and unending scrutiny by the International Association of Athletics Federations, following her victory in the 800 meters at the World Championships in Athletics in 2009. She was cleared the next year to continue competing as a woman, only to find that in 2018, the IAAF passed new a rule that barred her due to her high testosterone level.

At lower levels of sports, excluding trans athletes by prioritizing competitive balance over education and inclusion can have powerful consequences. Transgender teens have higher rates of suicidal ideation, plans and attempts than their cisgender peers, as well as higher rates of nonsuicidal self-injury. Gender discrimination and isolation are among the common reasons for suicide among trans people. While Ehardt argues that trans girls and women would be free to compete on boys’ and men’s teams, it’s a humiliating prospect that would do little to ease competitors’ gender dysphoria.

While supporters of the Idaho law argue that cisgender girls and women would be at a disadvantage against transgender competitors, the science remains unsettled. It’s known that people with testosterone-dominant bodies recover more quickly from physical activity than their estrogen-dominant counterparts, which leads to more muscle growth. One landmark study has shown that adult trans women experienced a statistically significant decrease in muscle mass after one year of testosterone suppression and cross-hormone therapy, though not nearly enough to put them on a level playing field with cisgender women. But those findings were from a small sample of nonathletes, and also cannot easily be applied to kids who are still undergoing puberty. There’s almost no research that’s been done on trans athletes, let alone young ones; it’s something that Joanna Harper, a Loughborough University Ph.D. student researching performance analysis in trans athletes, is working to address.

“What needs to happen over the next 10 to 12 years is we need to get some trans athletes into exercise labs,” says Harper, who has also advised the International Olympic Committee on its transgender-related policies. She points out that regardless of being transgender or cisgender, athletes have all kinds of advantages over each other: size, strength, skill, speed and endurance among them. As a trans runner herself, Harper noted that within weeks of beginning treatment, she was running more slowly, likely due to a lower red blood cell count, which affects how much oxygen the blood can take in from the lungs.

The idea that cisgender women need to be saved from stiff athletic competition is “a really dangerous road to go down because it just invokes all the stereotypes that we’re trying to get away from that girls and women need protecting in the first place,” says Heath Fogg Davis, the director of Temple University’s gender, sexuality, and women’s studies program.

Buzuvis, from Western New England University, agrees: “I think that if we weren’t so obsessed with promoting the idea of female athletic inferiority, we might actually discover that female athletes are better than we ever thought they were.”

In Connecticut, the other main battleground for trans rights in sports, one of the three cisgender girls who filed a federal lawsuit against transgender runners Andraya Yearwood and Terry Miller, backed by the ADF, actually ended up beating Miller days later in a 55-meter dash.

Like 17 other states, Connecticut currently allows transgender student-athletes to compete on the teams aligning with their gender identity. Twenty-six other states restrict trans participation either based on a birth certificate or on a case-by-case basis. As the lawsuit in Connecticut, which seeks to restrict transgender participation, works its way through the courts, trans athletes there can still compete—making Idaho the only state with a ban.

The NCAA and IOC take steps to regulate trans participation, but neither is nearly as aggressive as Idaho’s policy. A trans man, the NCAA says, may compete on the men’s team, no strings attached. A trans woman can compete on the women’s team after a year of hormone-suppression treatment. Meanwhile, in 2015, the IOC established that trans men may compete in men’s sports, and trans women in women’s sports, provided their testosterone levels stayed below 10 nanomoles per liter of blood for one year.

“When you have a high school athletic association that should be on the most inclusive end of the spectrum leapfrogging over all the other sport organizations in terms of making their policies the most restrictive, even more restrictive than the policies we’re seeing governed at the Olympic level, it’s just completely out of sync with what’s appropriate and what kind of values should be reflected in their policy,” Buzuvis says.

In fact, for its part, the NCAA is likely to protest Idaho’s ban by moving any championship games out of state, including first- and second-round games of the 2021 men’s basketball tournament. “Idaho’s House Bill 500 and resulting law is harmful to transgender student-athletes and conflicts with the NCAA’s core values of inclusivity, respect and the equitable treatment of all individuals,” it said in a June 11 statement. They’ll discuss the issue at an August Board of Governors meeting.

The NCAA’s statement came in response to a letter calling on the association to pull out from hosting any championship games in Idaho while the law remains in effect. Signees included professional, Olympic and Paralympic athletes, among them tennis legend Billie Jean King, USWNT star Megan Rapinoe, longtime Storm and Team USA point guard Sue Bird, and Knicks shooting guard Reggie Bullock, along with 500-plus student-athletes and advocacy organizations like Athlete Ally, a nonprofit dedicated to ending homophobia and transphobia in sports. In 2016, the NCAA moved events, including its basketball tournament matchups, out of North Carolina in light of the state’s bathroom bill, ending its prohibition only once state legislators repealed the law the following year.

“Obviously, if my sister was here and she wanted to play a sport, I don’t think what she classified herself as should be used against her,” says Bullock, an Athlete Ally ambassador whose late sister Mia Henderson was transgender. “It’s disrespectful to me in pretty much every way.”

King, arguably the main face of gender equality in all of sports, says in an email: “I’ve spent most of my life working for equality for all. Sport has given me an incredible platform because sports are a microcosm of society and can be used as a catalyst for social change. Everyone should be treated equally.”

***

While the Supreme Court made it clear that sex discrimination includes discrimination against transgender individuals, Hecox’s legal team will still have to prove that banning transgender girls and women from sports teams constitutes discrimination.

Some lower courts will begin applying the landmark ruling to other cases of discrimination right away, though some conservative judges may resist, says Jami Taylor, a University of Toledo political science professor who specializes in transgender issues. Multiple Title IX cases related to trans athletes could end up bouncing around circuit courts with different decisions—which is a recipe for one of them, though not necessarily Hecox’s, reaching the nation’s highest court. “I do think that case or a similar Title IX case is going to end up before the Supreme Court,” Taylor says in an email. She predicts that the court will allow trans participation, but with caveats—like those instituted by the NCAA and IOC to regulate trans female testosterone levels—and not the blanket inclusion that the court allowed with employment nondiscrimination.

Some experts, like Taylor, believe that a carve-out for transgender women and girls in the form of a testosterone requirement is reasonable to ensure they’re on a level playing field with their cisgender counterparts. Others, like Buzuvis, would like to see blanket inclusion. Still more, like Davis, would like to see gender-segregated sports end entirely in favor of the inclusion of all genders in any particular arena, though that is a more radical view. The range of opinions points to the complexity of the issue.

The outcome of Hecox v Little could also rest, in part, on public opinion, and people remain very divided on this issue—much more divided, Taylor says, than on workplace discrimination, where the Supreme Court essentially ratified a national consensus. “Does the court go look at public opinion polls and stick a finger in the wind? No,” she says. “But is the court part of the society it lives in?”

According to a January 2020 study published in the journal Sex Roles by Taylor and other researchers, the society it lives in isn’t sold: Just 35.6% of women and 23.2% of men believe trans athletes should participate in sports aligned with their gender identity.

“This really challenges people on a deep, deep level because it takes away a very deeply entrenched tradition that’s very much a part of our culture,” Davis says.

This is, in part, why Hecox believes it’s so important to share her story. She wants to put a human face on the issue, so that everyone can see that all she wants is to run.

“I don’t want to be just that one trans girl,” she says. “I want to be the runner who is really dedicated to the sport and tries her best every single day.”

0 Comments