A steal’s audacity is typically measured in just one dimension—its risk. But Andrelton Simmons's steal was more psychological warfare against the Astros on Monday.

A steal’s audacity is typically measured in just one dimension—its risk.

Which is a shame. Because there’s more than one path to audacity; there’s room for a gutsy steal whose gutsiness does not come simply from a mathematical evaluation of its probability. There is room, for example, for what Andrelton Simmons did on Monday.

The details of the situation do not matter too much. (For those inclined: Simmons was the only runner on with one out, top of the third, Angels down 2-0 to the Astros.) What matters is this:

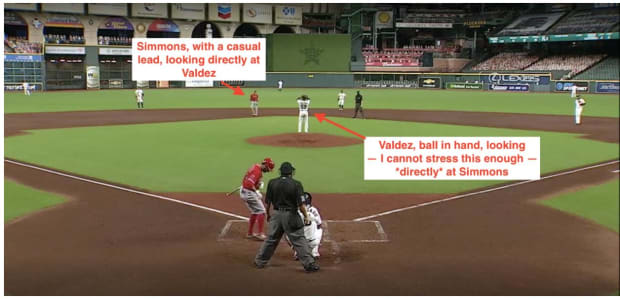

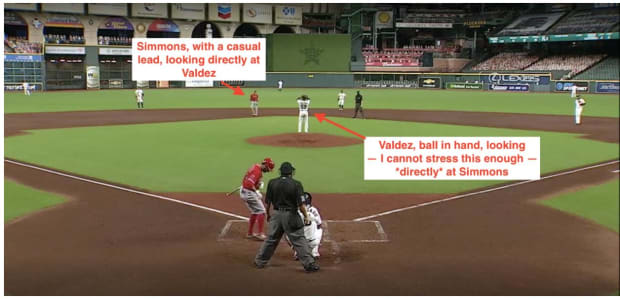

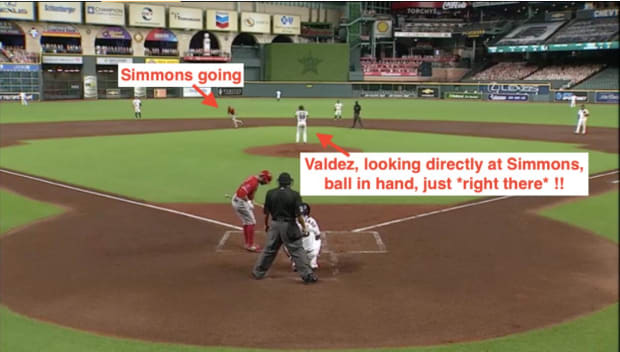

That is Framber Valdéz, who’d stepped off the mound and turned around to catch his breath. He took off his cap, wiped the sweat from his brow, a typical pause before a pitch. He faced Simmons—just looked right at him, which is generally what someone does when he turns around on the mound with a runner on second, because there is almost quite literally nowhere else to look.

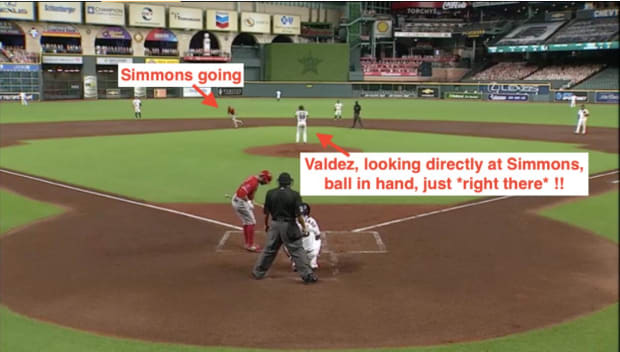

And then Simmons took off.

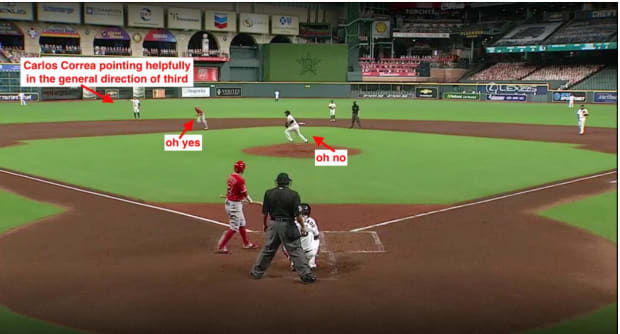

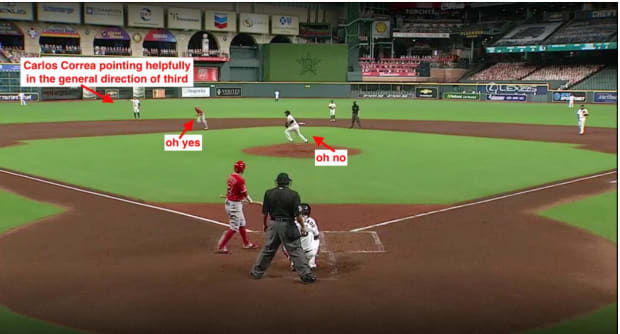

That’s not all on Valdéz. In fact, it’s not on him at all, really: Houston third baseman Jack Mayfield, whose positioning here took him off-camera, had far more to do with this steal than Valdéz did. Mayfield was playing a little bit deep and, for just a moment, was visibly distracted. (He appeared to have been engaged in the important task of inspecting the infield dirt.) This is what gave Simmons the opportunity to run. It’s also what made his steal rather un-gutsy—a clear window to make it over to third with less risk.

It’s what made Simmons’s steal “rather un-gutsy,” that is, if you’re defining gutsy strictly in the traditional sense as it tends to relate to steals. With Mayfield as distracted as he was, Simmons had a decent chance of pulling it off successfully, if not comfortably. But with any other definition of “gutsy”—My God! Don’t think about the risk. Just think about the aesthetics. Valdéz looks directly at Simmons; Simmons looks directly at him; Valdéz grips the ball loosely, casually, unthinkingly. He has all that he could need to block a steal—a clear view, plenty of time, ball in hand. This should be so easy to stop.

But Valdez—again, by no real fault of his own!—can’t do it.

If every steal requires some level of psychological warfare—some bit of trickery or surprise or misplaced trust—here is one of the boldest versions conceivable. There’s no deceit. There’s no gotcha. There is only Simmons making eye contact with Valdéz, an invitation to watch him take a base, as both of them realize that there isn’t anything that the pitcher can do about it. It’s so gutsy as to be almost downright disrespectful.

Simmons scored, but the steal itself did not mean much. (Valdéz went on to get both the win and a personal-best 11 Ks.) It just, for a moment, rewrote the definition of “gutsy”— looked it straight in the eyes and ran on it.

Quick Hits

• In a season that has included ads in the ‘pen, the stands, and the on-deck circle—such is the cost of doing business in a pandemic—baseball reached a new level on Monday. After a beer company offered to do a

temporary name-change in honor of Trevor Bauer if he managed 14 Ks in two starts, Bauer engaged in some in-game sponsored content, writing the company name on the mound, and pretending to crack a cold one after he got the necessary strikeouts. Now, more than ever: everything is advertising.• Not one but two home runs for Javy Báez in the Cubs’ win over the Tigers:

• In Cleveland’s 3–2 loss to Minnesota, the broadcast spent several minutes on this, er, “fun” fact, and thank goodness they did:

A steal’s audacity is typically measured in just one dimension—its risk. But Andrelton Simmons's steal was more psychological warfare against the Astros on Monday.

A steal’s audacity is typically measured in just one dimension—its risk.

Which is a shame. Because there’s more than one path to audacity; there’s room for a gutsy steal whose gutsiness does not come simply from a mathematical evaluation of its probability. There is room, for example, for what Andrelton Simmons did on Monday.

The details of the situation do not matter too much. (For those inclined: Simmons was the only runner on with one out, top of the third, Angels down 2-0 to the Astros.) What matters is this:

That is Framber Valdéz, who’d stepped off the mound and turned around to catch his breath. He took off his cap, wiped the sweat from his brow, a typical pause before a pitch. He faced Simmons—just looked right at him, which is generally what someone does when he turns around on the mound with a runner on second, because there is almost quite literally nowhere else to look.

And then Simmons took off.

That’s not all on Valdéz. In fact, it’s not on him at all, really: Houston third baseman Jack Mayfield, whose positioning here took him off-camera, had far more to do with this steal than Valdéz did. Mayfield was playing a little bit deep and, for just a moment, was visibly distracted. (He appeared to have been engaged in the important task of inspecting the infield dirt.) This is what gave Simmons the opportunity to run. It’s also what made his steal rather un-gutsy—a clear window to make it over to third with less risk.

It’s what made Simmons’s steal “rather un-gutsy,” that is, if you’re defining gutsy strictly in the traditional sense as it tends to relate to steals. With Mayfield as distracted as he was, Simmons had a decent chance of pulling it off successfully, if not comfortably. But with any other definition of “gutsy”—My God! Don’t think about the risk. Just think about the aesthetics. Valdéz looks directly at Simmons; Simmons looks directly at him; Valdéz grips the ball loosely, casually, unthinkingly. He has all that he could need to block a steal—a clear view, plenty of time, ball in hand. This should be so easy to stop.

But Valdez—again, by no real fault of his own!—can’t do it.

If every steal requires some level of psychological warfare—some bit of trickery or surprise or misplaced trust—here is one of the boldest versions conceivable. There’s no deceit. There’s no gotcha. There is only Simmons making eye contact with Valdéz, an invitation to watch him take a base, as both of them realize that there isn’t anything that the pitcher can do about it. It’s so gutsy as to be almost downright disrespectful.

Simmons scored, but the steal itself did not mean much. (Valdéz went on to get both the win and a personal-best 11 Ks.) It just, for a moment, rewrote the definition of “gutsy”— looked it straight in the eyes and ran on it.

Quick Hits

• In a season that has included ads in the ‘pen, the stands, and the on-deck circle—such is the cost of doing business in a pandemic—baseball reached a new level on Monday. After a beer company offered to do a temporary name-change in honor of Trevor Bauer if he managed 14 Ks in two starts, Bauer engaged in some in-game sponsored content, writing the company name on the mound, and pretending to crack a cold one after he got the necessary strikeouts. Now, more than ever: everything is advertising.

• Not one but two home runs for Javy Báez in the Cubs’ win over the Tigers:

• In Cleveland’s 3–2 loss to Minnesota, the broadcast spent several minutes on this, er, “fun” fact, and thank goodness they did:

0 Comments