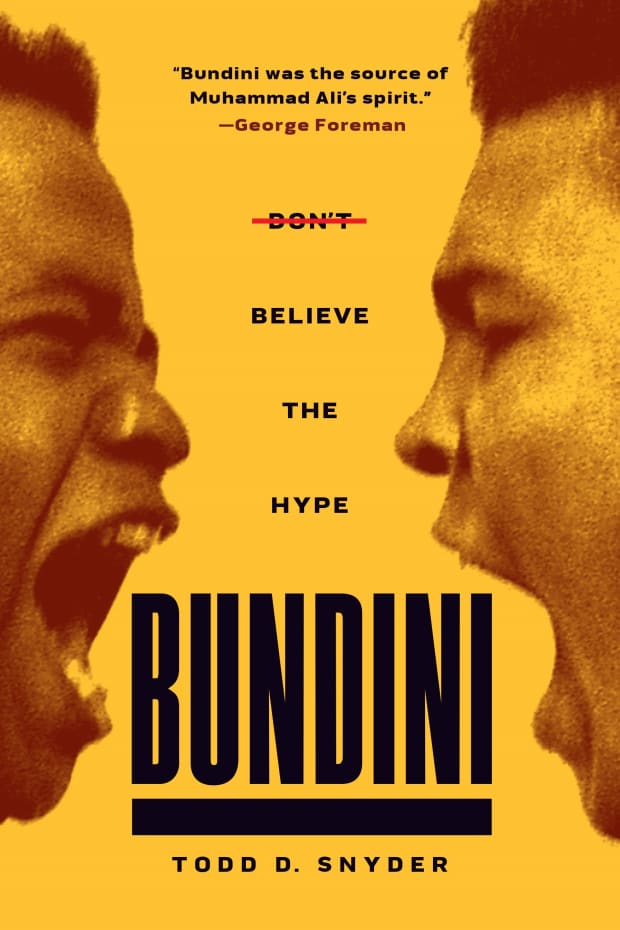

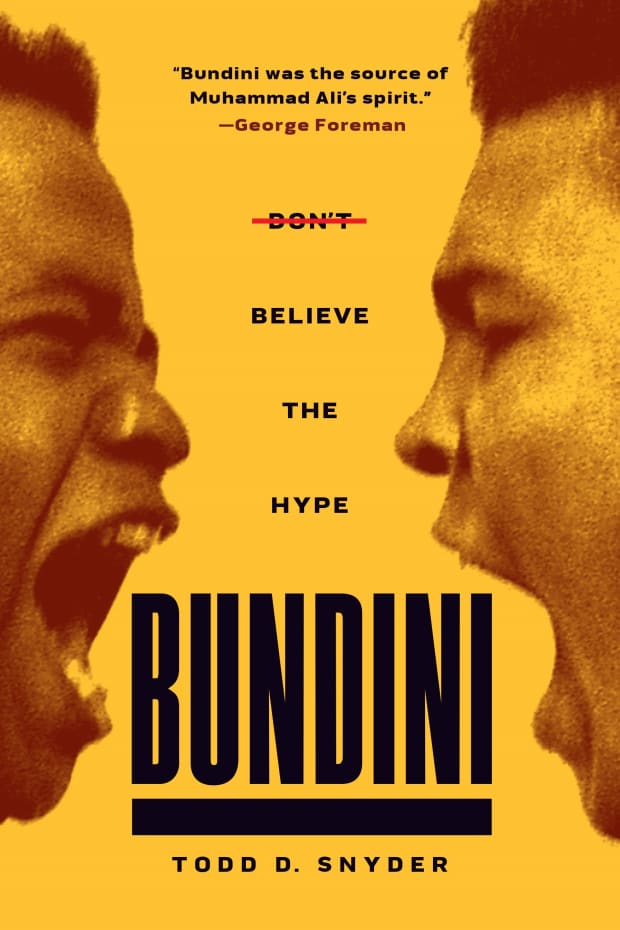

In an excerpt from Don't Believe the Hype, author Todd Snyder looks back at how Bundini Brown's relationship with Sugar Ray Robinson paved the way for Muhammad Ali and the greatest show on earth.

From Bundini:

Don’t Believe the Hype by Todd D. Snyder. ©2020 by Todd D. Snyder. Reprinted by permission of Hamilcar Publications. All rights reserved.The flamingo-pink Cadillac slowly pulled up to the curb and men climbed over each other, pushing and shoving, while women shouted and whistled through rouge-red lips. Dressed in an exotic zoot suit and accompanied by his beautiful wife, the great Sugar Ray Robinson entered Shelton’s Rib House to a king’s welcome. Signing autographs and waiting to be seated, the Champ spotted an elderly Black woman dining alone at a table by the window, her crutches resting in the opposite chair.

“Make sure that lady’s meal is taken care of,” Robinson instructed, tossing a five-dollar bill to the cashier.

“Champ, they ’ll be falling in the ring, and you won’t know why they falling,” the cashier replied, collecting the money. “Shorty is gonna take care of you,” the cashier added.

To this Robinson flashed a look of confusion.

“Shorty?” Robinson inquired.

“Call him Shorty,” the cashier answered, his eyes glancing toward the elderly woman. “Call him Shorty because he takes care of the little guy,” he added.

“What the hell you talkin’ about?” Robinson laughed.

“That lady over by the window, that’s Shorty. That’s Shorty checkin’ in on you, testin’ you,” the cashier replied.

Robinson, perplexed by the homespun doctrine, offered no response.

“Tonight, you passed the test, Champ. I feel sorry for the next man face you,” the cashier philosophized.

“What’s your name, brother?” Robinson asked, unaware the two had previously met.

“Some call me Bundini. Others call me Fast Black,” the cashier responded, unfazed by Robinson’s celebrity.

“Well, you a strange nigger, Bundini. Very strange,” Robinson smirked, grinning that million-dollar smile, extending a handshake.

“Give me the little ones,” Bundini replied, gesturing toward Robinson’s pinky finger, his thumb removed from the exchange. “The big ones can take care of themselves,” he added.

In the private dining area, a few moments later, Robinson relayed the conversation to his brother-in-law, Bob Nelson. Nelson reminded Robinson of Bundini’s work with Johnny Bratton, the gloves he had signed for his newborn child.

“See if he needs extra work. I’ll put him to work,” Robinson told his brother-in-law.

“From then on, I was not one among many to him, I was just me,” Bundini would later reflect.

One of the great mysteries of Drew Bundini Brown’s boxing career, perhaps the least documented aspect of his professional resumé, is his role within Sugar Ray Robinson’s entourage. Such an exploration requires one to reexamine the term entourage itself. In many ways, our modern-day understanding of the term begins with Robinson. Long before “Iron” Mike Tyson and Floyd “Money” Mayweather, Sugar Ray Robinson crafted a public persona of supreme dominance and flamboyant extravagance, a shadow so brilliantly cast that even his lackeys gained some measure of fame. Robinson cared a great deal about maintaining this image. His entourage was a key component in crafting it. From the clothes to the cars, everything the Champ did was marked by over-the-top excess. When Robinson hit the road, for example, his crew typically consisted of Millie Robinson (his wife), Bob Nelson (his brother-in-law), George Gainford (his manager), Rogers Simon (his personal barber and cornerman), Harry Wiley (his trainer), other assistant trainers, a secretary, a professional golf instructor, and a dwarf nicknamed Arabian Knight (serving the role of court jester). Among the traveling crew were a collection of cronies Robinson referred to as “odd-job men.” It is estimated Robinson ’ s entourage carried “100 pieces of luggage among them, and cost about $3,000 a week” to support. Rolling with the Champ, as one might assume, came with many of the perks of being the Champ. Robinson famously wined and dined members of his team.

Despite his brief apprenticeship with Johnny Bratton, Bundini, one can safely assume, began his tenure as a member of Team Robinson as an “odd-job man.” Much of his work would have had nothing to do with boxing. Recalling his father’s well-known history of philandering, Robinson II writes, “My father would take me with him to various places where he hung out. . . . He would drop me off with Bundini (Brown) at the Apollo or leave me in the lobby of the Theresa Hotel when Charlie Rangel was the desk clerk, while he went out and checked his ‘traps,’ his various female partners.”

It appears that Bundini spent much of 1956 partaking in such menial duties, running errands, babysitting, and earning the Champ’s trust. By the time Robinson faced Gene Fullmer at Madison Square Garden on January 2, 1957, however, Bundini’s role in the entourage was fully solidified.

“It started with those Fullmer fights. I know for a fact that Bundini went to camp with Robinson for those fights. I remember him talking about those training camps,” former heavyweight contender and future Bundini pupil James “Quick” Tillis told me.

The invitation to accompany Robinson to training camp ended Bundini’s time as a cashier at Shelton’s Rib House, effective immediately.

For much of the Champ’s storied career, the village of Greenwood Lake, located just outside of Poughkeepsie, New York, served as the headquarters for his ring preparation. Fifty miles north of New York City, the lakeside community, known for boating, skiing, and hiking on the nearby Appalachian Trail, offered seclusion from the distractions of Manhattan nightlife. Rocky Marciano and Joe Louis also used the facilities throughout their careers. The fighters stayed in cabins, training facilities were erected amid the beautiful wilderness, and, on occasion, locals were invited to watch the champions train. Summers were picturesque and winters were brutal. The setup, one might argue, was a precursor to Muhammad Ali’s Deer Lake training camp in Pennsylvania.

For the twenty-eight-year-old Bundini, the experience of total immersion into the daily life of a world-class fighter would have been nothing short of an education, the experience different in every way from his time working with Johnny Bratton in Harlem. Spokes in a wheel, each member of Team Robinson dedicated their time to creating an atmosphere where the Champ could best mentally and physically prepare himself for the rigors of fifteen-round prizefighting. Working for the Champ was an around-the-clock job.

In Pound for Pound: A Biography of Sugar Ray Robinson, Sugar Ray Robinson II and author Herb Boyd evoke a commonly known Bundini/Robinson story, perhaps providing a window into his early days as a member of Robinson's team:

There’s an incident in Ali’s autobiography related by Bundini Brown, who was a trainer with Sugar before he joined Ali’s team. He writes about his sleeping with “a champ” who is the best fighter in the world, “pound for pound.” “I was green,” Bundini said. “First time I’d been with a champ. No woman had ever asked me to get in bed with her husband before, and I didn’t know what to make of it.” “Just lie in bed with him,” she says . . . . He’s lying there in bed and I get in and lie next to him, and he cuddles up with my arms around him and goes to sleep . . . . By all indications, the man Bundini is cuddling is Sugar.

It is quite possible that Millie Robinson did order Bundini to bunk with her husband; in those days abstaining from sex before a fight was a key precautionary measure. While research suggests Millie did often stay with Robinson in Greenwood Lake, it is likely that she did not sleep with him. Regardless, all signs indicate that Sugar Ray took to Bundini. In just a few quick years, Bundini went from being elated to hang a pair of autographed Sugar Ray gloves above his son’s crib to actually sleeping in the same bed as the champion.

“I didn’t know what I was doing then, but it was the same as it is now—a spirit thing. But, like George Gainford once told me, ‘Wherever you are and whatever you are doing, make sure whenever you leave you are missed,’” Bundini once told Sports Illustrated.

After the first Fullmer fight, when it came time to pay Bundini for his services, Robinson did so in cash. A handshake was all Bundini required as a contract.

“Pay me whatever Champ thinks I’m worth,” Bundini negotiated with Gainford, a flawed system that would carry over to Bundini’s time with Muhammad Ali.

The money often disappeared as quickly as it came.

When Bundini officially joined the Sugar Ray Robinson payroll in 1957, the dynamics of his relationship with his wife, Rhoda, once again began to shift. The job required that he spend much of his time at Greenwood Lake and traveling with Robinson to fights. This is not to suggest Bundini ’s new life was without its perks. Rhoda, Drew Brown III, and her parents would, on occasion, get to travel to Greenwood Lake to watch Sugar Ray train.

“My most vivid memory is watching Uncle Ray on the speed bag,” Drew Brown III recalled. “He would knock it off the hinges and it would go sprawling across the floor.”

The occasional visits to Greenwood Lake, however, did little to mend what was becoming an increasingly fractured marriage. Rhoda, a dynamic and independent woman, simply was not “housewife material.” She had, in many respects, lost her jazz-joint partner. She had lost the danger that lured her away from Brighton Beach. She was now a devoted mother and provider. Bundini, on the other hand, was swooped up into a new and exciting world, enjoying all of the attention and perks and temptations that went along with being a member of the Sugar Ray entourage. The atmosphere not only took him away from his family but transformed him from a Harlem celebrity to a national celebrity.

“I always believed that we could be a well-adjusted, happy family. I dreamed of having a good family. And I always knew that, one day, he would make it big, and be a success in some way. But I really thought that he would then share that success with me and you. That’s what I wanted more than anything else in the world,” Rhoda wrote to her son, looking back on the final year of her marriage to Drew Bundini Brown.

“Daddy, what are you doing?” Drew Brown III called, walking into his parents’ bedroom, taking in the sight of his father slowly putting on and tying his alligator shoes. The three-year-old ’ s eyes were drawn to the suitcases stacked behind his father. He sat next to his father on the bed.

“Sneezer, it’s time for me to go,” Bundini replied, his voice soft and wavering.

“You going to see Uncle Ray?” the boy asked, wishfully thinking, perhaps.

Bundini shook his head in disagreement.

“When are you coming back?” the boy asked, masking his trepidation.

“Sneezer, I ’m leaving. But, I ’ll always be your Daddy,” Bundini answered.

“I won ’t be able to live here anymore. You ’ll be better off if I leave.”

The young boy protested to no avail.

“I ’ll come visit you, from time to time,” Bundini assured, tears forming in the corners of his eyes. “You ’ll have other fathers in your life.”

The child violently protested. “No! You ’re my only Daddy. I only want you. When are you coming back?”

“I will always be your Daddy, I will always look out for you. I just can’t live here anymore but I ’ll never leave you.”

Rhoda Palestine and Drew Brown ended their six-year marriage in early 1958. The separation came as a result of the most explosive and turbulent period of their time together.

“Once Daddy started making it, he changed, towards my mommy,” Drew Brown III told me. “They had been equals. Now that he started to see the possibility of prosperity, he wanted to be in charge. He wanted to be the man. He wanted my mother to give in to his every wish. She was not one of those ‘stand by your man regardless’ type of women. She was not subservient.”

Because of the constant demands of Sugar Ray's busy schedule—Robinson was one of the busiest fighters of any generation—Bundini was rarely home. His new life also impacted Rhoda’s newfound unwillingness to accept her husband’s promiscuity. Rhoda, as one might imagine, was envious of the privileges her husband now enjoyed. While Bundini traveled, Rhoda was left home with their child, living off of government assistance. Two stubborn and unyielding personalities, neither partner would back down or relent to the other. Bundini, adept at talking his way out of any situation, had met his rhetorical match. As the arguments became increasingly volatile, Rhoda and Bundini came to the mutual realization that their marriage was no longer worth saving.

“The divorce divided not much money in half—zero divided by zero is still zero—so we all suffered financially,” Drew III reflected.

When Bundini wasn’t traveling with Sugar Ray, he stayed at a small apartment on West 86th Street, a space he shared with a revolving door of new girlfriends. Rhoda and her son lived at the Carver House, a government-subsidized housing project at 60 East 102nd Street, between Park and Madison. The mother and son moved into apartment 11-F.

A fifty-five-cent cab ride away in Spanish Harlem, in an eleventh-floor two-bedroom unit, Rhoda and her son began a new phase in their lives.

Just as Rhoda and Bundini approached marriage in an unconventional fashion, so did the couple embrace the concept of divorce with their own unique style. Even after the separation, Bundini would often stay at the apartment with his ex-wife and son. These visits sometimes extended to weeks at a time. When the arguments picked back up, Bundini would disappear. The unpredictability of Bundini’s visitation schedule took a heavy toll on his son, who, as the years passed, obsessively worked to reunite his parents. Christmas soon became the only time of the year when differences were put aside.

“No matter how bad things got, there was always a holiday truce from fighting in our house. Both of my parents celebrated Christmas, not in a religious sense, but in a festive one,” Drew III recalled.

“Daddy always came through on Christmas. It might be midnight before he arrived, but he never failed to show up, laughing, joking, and brandishing an armload of packages,” he added.

On occasion, Bundini’s famous employer would play Santa Claus to the young boy, providing a Christmas bonus that would allow him to purchase toy six-shooters, punching bags, or whatever else the boy wanted.

On the road, meeting celebrities and tending to the needs of boxing’s most celebrated champion, every day must have felt like Christmas for Bundini. As a member of Team Robinson, he partook in headlining events at Madison Square Garden and the Convention Center in Las Vegas and experienced the nightlife of cities such as Los Angeles, Detroit, Miami, and even Honolulu. And just as he had earned a reputation as the Black Prince of Manhattan’s jazz clubs, Bundini gradually became known in boxing circles. With this notoriety came famous friendships with Joe Louis, James Baldwin, Norman Mailer, and Lloyd Price. For a brief period, Bundini had an affair with up-and-coming R&B singer Ruth Brown. As his bond with Robinson grew, Bundini became a chief presence in the entourage.

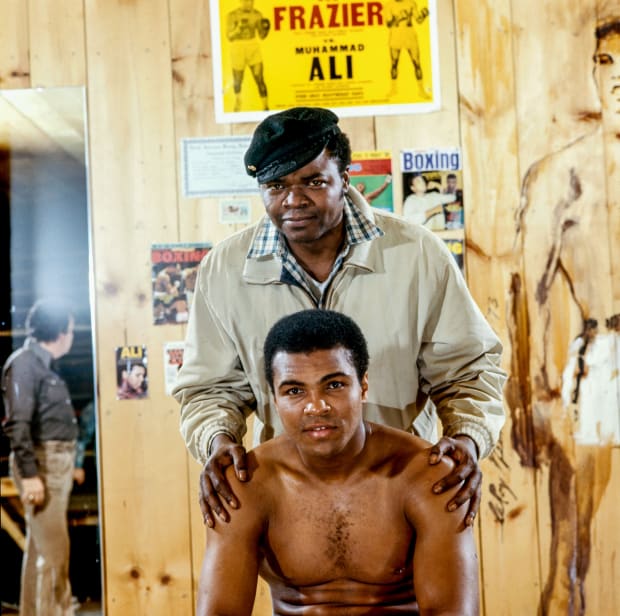

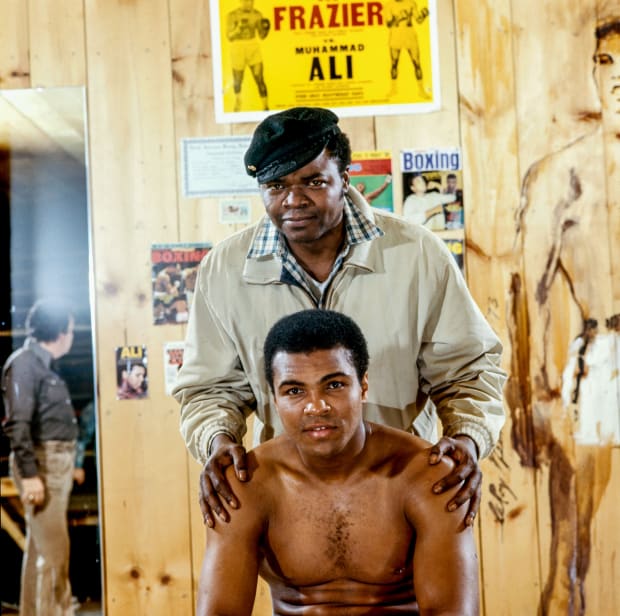

At the Greenwood Lake training facility, Bundini oversaw every aspect of Robinson’s preparation. For seven straight years, he fulfilled the role of Sugar Ray’s personal motivator, leaning over the ropes during sparring sessions, cheering him on as he worked the double-end bag, urging him to victory from ringside. Robinson, who often referred to Bundini as “Boone,” fed off this energy, responded to it, and eventually came to rely on it.

“We worked together for seven years. I am proud of my association with Bundini. I extremely admire him. He is the best motivator I know in the fight game,” Robinson once wrote.

During his apprenticeship Bundini discovered the psychological side of prizefighting, developing and sharpening his skills as a motivator. His unique ability to read personalities and tailor his oratory to the needs of the individual undoubtedly served him well. Just as he had done at the counter of Shelton’s Rib House, Bundini captured his boss’s imagination, motivated him to action. Working his way up to the title of assistant trainer of the great Sugar Ray, even for an ultimate optimist like Drew Bundini Brown, had to feel like the accomplishment of a lifetime. He couldn’t have possibly foreseen that Robinson would not be his most famous business partner. Drew Bundini Brown’s career in boxing was, in many respects, just beginning.

In an excerpt from Don't Believe the Hype, author Todd Snyder looks back at how Bundini Brown's relationship with Sugar Ray Robinson paved the way for Muhammad Ali and the greatest show on earth.

From Bundini: Don’t Believe the Hype by Todd D. Snyder. ©2020 by Todd D. Snyder. Reprinted by permission of Hamilcar Publications. All rights reserved.

The flamingo-pink Cadillac slowly pulled up to the curb and men climbed over each other, pushing and shoving, while women shouted and whistled through rouge-red lips. Dressed in an exotic zoot suit and accompanied by his beautiful wife, the great Sugar Ray Robinson entered Shelton’s Rib House to a king’s welcome. Signing autographs and waiting to be seated, the Champ spotted an elderly Black woman dining alone at a table by the window, her crutches resting in the opposite chair.

“Make sure that lady’s meal is taken care of,” Robinson instructed, tossing a five-dollar bill to the cashier.

“Champ, they ’ll be falling in the ring, and you won’t know why they falling,” the cashier replied, collecting the money. “Shorty is gonna take care of you,” the cashier added.

To this Robinson flashed a look of confusion.

“Shorty?” Robinson inquired.

“Call him Shorty,” the cashier answered, his eyes glancing toward the elderly woman. “Call him Shorty because he takes care of the little guy,” he added.

“What the hell you talkin’ about?” Robinson laughed.

“That lady over by the window, that’s Shorty. That’s Shorty checkin’ in on you, testin’ you,” the cashier replied.

Robinson, perplexed by the homespun doctrine, offered no response.

“Tonight, you passed the test, Champ. I feel sorry for the next man face you,” the cashier philosophized.

“What’s your name, brother?” Robinson asked, unaware the two had previously met.

“Some call me Bundini. Others call me Fast Black,” the cashier responded, unfazed by Robinson’s celebrity.

“Well, you a strange nigger, Bundini. Very strange,” Robinson smirked, grinning that million-dollar smile, extending a handshake.

“Give me the little ones,” Bundini replied, gesturing toward Robinson’s pinky finger, his thumb removed from the exchange. “The big ones can take care of themselves,” he added.

In the private dining area, a few moments later, Robinson relayed the conversation to his brother-in-law, Bob Nelson. Nelson reminded Robinson of Bundini’s work with Johnny Bratton, the gloves he had signed for his newborn child.

“See if he needs extra work. I’ll put him to work,” Robinson told his brother-in-law.

“From then on, I was not one among many to him, I was just me,” Bundini would later reflect.

One of the great mysteries of Drew Bundini Brown’s boxing career, perhaps the least documented aspect of his professional resumé, is his role within Sugar Ray Robinson’s entourage. Such an exploration requires one to reexamine the term entourage itself. In many ways, our modern-day understanding of the term begins with Robinson. Long before “Iron” Mike Tyson and Floyd “Money” Mayweather, Sugar Ray Robinson crafted a public persona of supreme dominance and flamboyant extravagance, a shadow so brilliantly cast that even his lackeys gained some measure of fame. Robinson cared a great deal about maintaining this image. His entourage was a key component in crafting it. From the clothes to the cars, everything the Champ did was marked by over-the-top excess. When Robinson hit the road, for example, his crew typically consisted of Millie Robinson (his wife), Bob Nelson (his brother-in-law), George Gainford (his manager), Rogers Simon (his personal barber and cornerman), Harry Wiley (his trainer), other assistant trainers, a secretary, a professional golf instructor, and a dwarf nicknamed Arabian Knight (serving the role of court jester). Among the traveling crew were a collection of cronies Robinson referred to as “odd-job men.” It is estimated Robinson ’ s entourage carried “100 pieces of luggage among them, and cost about $3,000 a week” to support. Rolling with the Champ, as one might assume, came with many of the perks of being the Champ. Robinson famously wined and dined members of his team.

Despite his brief apprenticeship with Johnny Bratton, Bundini, one can safely assume, began his tenure as a member of Team Robinson as an “odd-job man.” Much of his work would have had nothing to do with boxing. Recalling his father’s well-known history of philandering, Robinson II writes, “My father would take me with him to various places where he hung out. . . . He would drop me off with Bundini (Brown) at the Apollo or leave me in the lobby of the Theresa Hotel when Charlie Rangel was the desk clerk, while he went out and checked his ‘traps,’ his various female partners.”

It appears that Bundini spent much of 1956 partaking in such menial duties, running errands, babysitting, and earning the Champ’s trust. By the time Robinson faced Gene Fullmer at Madison Square Garden on January 2, 1957, however, Bundini’s role in the entourage was fully solidified.

“It started with those Fullmer fights. I know for a fact that Bundini went to camp with Robinson for those fights. I remember him talking about those training camps,” former heavyweight contender and future Bundini pupil James “Quick” Tillis told me.

The invitation to accompany Robinson to training camp ended Bundini’s time as a cashier at Shelton’s Rib House, effective immediately.

For much of the Champ’s storied career, the village of Greenwood Lake, located just outside of Poughkeepsie, New York, served as the headquarters for his ring preparation. Fifty miles north of New York City, the lakeside community, known for boating, skiing, and hiking on the nearby Appalachian Trail, offered seclusion from the distractions of Manhattan nightlife. Rocky Marciano and Joe Louis also used the facilities throughout their careers. The fighters stayed in cabins, training facilities were erected amid the beautiful wilderness, and, on occasion, locals were invited to watch the champions train. Summers were picturesque and winters were brutal. The setup, one might argue, was a precursor to Muhammad Ali’s Deer Lake training camp in Pennsylvania.

For the twenty-eight-year-old Bundini, the experience of total immersion into the daily life of a world-class fighter would have been nothing short of an education, the experience different in every way from his time working with Johnny Bratton in Harlem. Spokes in a wheel, each member of Team Robinson dedicated their time to creating an atmosphere where the Champ could best mentally and physically prepare himself for the rigors of fifteen-round prizefighting. Working for the Champ was an around-the-clock job.

In Pound for Pound: A Biography of Sugar Ray Robinson, Sugar Ray Robinson II and author Herb Boyd evoke a commonly known Bundini/Robinson story, perhaps providing a window into his early days as a member of Robinson's team:

There’s an incident in Ali’s autobiography related by Bundini Brown, who was a trainer with Sugar before he joined Ali’s team. He writes about his sleeping with “a champ” who is the best fighter in the world, “pound for pound.” “I was green,” Bundini said. “First time I’d been with a champ. No woman had ever asked me to get in bed with her husband before, and I didn’t know what to make of it.” “Just lie in bed with him,” she says . . . . He’s lying there in bed and I get in and lie next to him, and he cuddles up with my arms around him and goes to sleep . . . . By all indications, the man Bundini is cuddling is Sugar.

It is quite possible that Millie Robinson did order Bundini to bunk with her husband; in those days abstaining from sex before a fight was a key precautionary measure. While research suggests Millie did often stay with Robinson in Greenwood Lake, it is likely that she did not sleep with him. Regardless, all signs indicate that Sugar Ray took to Bundini. In just a few quick years, Bundini went from being elated to hang a pair of autographed Sugar Ray gloves above his son’s crib to actually sleeping in the same bed as the champion.

“I didn’t know what I was doing then, but it was the same as it is now—a spirit thing. But, like George Gainford once told me, ‘Wherever you are and whatever you are doing, make sure whenever you leave you are missed,’” Bundini once told Sports Illustrated.

After the first Fullmer fight, when it came time to pay Bundini for his services, Robinson did so in cash. A handshake was all Bundini required as a contract.

“Pay me whatever Champ thinks I’m worth,” Bundini negotiated with Gainford, a flawed system that would carry over to Bundini’s time with Muhammad Ali.

The money often disappeared as quickly as it came.

When Bundini officially joined the Sugar Ray Robinson payroll in 1957, the dynamics of his relationship with his wife, Rhoda, once again began to shift. The job required that he spend much of his time at Greenwood Lake and traveling with Robinson to fights. This is not to suggest Bundini ’s new life was without its perks. Rhoda, Drew Brown III, and her parents would, on occasion, get to travel to Greenwood Lake to watch Sugar Ray train.

“My most vivid memory is watching Uncle Ray on the speed bag,” Drew Brown III recalled. “He would knock it off the hinges and it would go sprawling across the floor.”

The occasional visits to Greenwood Lake, however, did little to mend what was becoming an increasingly fractured marriage. Rhoda, a dynamic and independent woman, simply was not “housewife material.” She had, in many respects, lost her jazz-joint partner. She had lost the danger that lured her away from Brighton Beach. She was now a devoted mother and provider. Bundini, on the other hand, was swooped up into a new and exciting world, enjoying all of the attention and perks and temptations that went along with being a member of the Sugar Ray entourage. The atmosphere not only took him away from his family but transformed him from a Harlem celebrity to a national celebrity.

“I always believed that we could be a well-adjusted, happy family. I dreamed of having a good family. And I always knew that, one day, he would make it big, and be a success in some way. But I really thought that he would then share that success with me and you. That’s what I wanted more than anything else in the world,” Rhoda wrote to her son, looking back on the final year of her marriage to Drew Bundini Brown.

“Daddy, what are you doing?” Drew Brown III called, walking into his parents’ bedroom, taking in the sight of his father slowly putting on and tying his alligator shoes. The three-year-old ’ s eyes were drawn to the suitcases stacked behind his father. He sat next to his father on the bed.

“Sneezer, it’s time for me to go,” Bundini replied, his voice soft and wavering.

“You going to see Uncle Ray?” the boy asked, wishfully thinking, perhaps.

Bundini shook his head in disagreement.

“When are you coming back?” the boy asked, masking his trepidation.

“Sneezer, I ’m leaving. But, I ’ll always be your Daddy,” Bundini answered.

“I won ’t be able to live here anymore. You ’ll be better off if I leave.”

The young boy protested to no avail.

“I ’ll come visit you, from time to time,” Bundini assured, tears forming in the corners of his eyes. “You ’ll have other fathers in your life.”

The child violently protested. “No! You ’re my only Daddy. I only want you. When are you coming back?”

“I will always be your Daddy, I will always look out for you. I just can’t live here anymore but I ’ll never leave you.”

Rhoda Palestine and Drew Brown ended their six-year marriage in early 1958. The separation came as a result of the most explosive and turbulent period of their time together.

“Once Daddy started making it, he changed, towards my mommy,” Drew Brown III told me. “They had been equals. Now that he started to see the possibility of prosperity, he wanted to be in charge. He wanted to be the man. He wanted my mother to give in to his every wish. She was not one of those ‘stand by your man regardless’ type of women. She was not subservient.”

Because of the constant demands of Sugar Ray's busy schedule—Robinson was one of the busiest fighters of any generation—Bundini was rarely home. His new life also impacted Rhoda’s newfound unwillingness to accept her husband’s promiscuity. Rhoda, as one might imagine, was envious of the privileges her husband now enjoyed. While Bundini traveled, Rhoda was left home with their child, living off of government assistance. Two stubborn and unyielding personalities, neither partner would back down or relent to the other. Bundini, adept at talking his way out of any situation, had met his rhetorical match. As the arguments became increasingly volatile, Rhoda and Bundini came to the mutual realization that their marriage was no longer worth saving.

“The divorce divided not much money in half—zero divided by zero is still zero—so we all suffered financially,” Drew III reflected.

When Bundini wasn’t traveling with Sugar Ray, he stayed at a small apartment on West 86th Street, a space he shared with a revolving door of new girlfriends. Rhoda and her son lived at the Carver House, a government-subsidized housing project at 60 East 102nd Street, between Park and Madison. The mother and son moved into apartment 11-F.

A fifty-five-cent cab ride away in Spanish Harlem, in an eleventh-floor two-bedroom unit, Rhoda and her son began a new phase in their lives.

Just as Rhoda and Bundini approached marriage in an unconventional fashion, so did the couple embrace the concept of divorce with their own unique style. Even after the separation, Bundini would often stay at the apartment with his ex-wife and son. These visits sometimes extended to weeks at a time. When the arguments picked back up, Bundini would disappear. The unpredictability of Bundini’s visitation schedule took a heavy toll on his son, who, as the years passed, obsessively worked to reunite his parents. Christmas soon became the only time of the year when differences were put aside.

“No matter how bad things got, there was always a holiday truce from fighting in our house. Both of my parents celebrated Christmas, not in a religious sense, but in a festive one,” Drew III recalled.

“Daddy always came through on Christmas. It might be midnight before he arrived, but he never failed to show up, laughing, joking, and brandishing an armload of packages,” he added.

On occasion, Bundini’s famous employer would play Santa Claus to the young boy, providing a Christmas bonus that would allow him to purchase toy six-shooters, punching bags, or whatever else the boy wanted.

On the road, meeting celebrities and tending to the needs of boxing’s most celebrated champion, every day must have felt like Christmas for Bundini. As a member of Team Robinson, he partook in headlining events at Madison Square Garden and the Convention Center in Las Vegas and experienced the nightlife of cities such as Los Angeles, Detroit, Miami, and even Honolulu. And just as he had earned a reputation as the Black Prince of Manhattan’s jazz clubs, Bundini gradually became known in boxing circles. With this notoriety came famous friendships with Joe Louis, James Baldwin, Norman Mailer, and Lloyd Price. For a brief period, Bundini had an affair with up-and-coming R&B singer Ruth Brown. As his bond with Robinson grew, Bundini became a chief presence in the entourage.

At the Greenwood Lake training facility, Bundini oversaw every aspect of Robinson’s preparation. For seven straight years, he fulfilled the role of Sugar Ray’s personal motivator, leaning over the ropes during sparring sessions, cheering him on as he worked the double-end bag, urging him to victory from ringside. Robinson, who often referred to Bundini as “Boone,” fed off this energy, responded to it, and eventually came to rely on it.

“We worked together for seven years. I am proud of my association with Bundini. I extremely admire him. He is the best motivator I know in the fight game,” Robinson once wrote.

During his apprenticeship Bundini discovered the psychological side of prizefighting, developing and sharpening his skills as a motivator. His unique ability to read personalities and tailor his oratory to the needs of the individual undoubtedly served him well. Just as he had done at the counter of Shelton’s Rib House, Bundini captured his boss’s imagination, motivated him to action. Working his way up to the title of assistant trainer of the great Sugar Ray, even for an ultimate optimist like Drew Bundini Brown, had to feel like the accomplishment of a lifetime. He couldn’t have possibly foreseen that Robinson would not be his most famous business partner. Drew Bundini Brown’s career in boxing was, in many respects, just beginning.

0 Comments