A few weeks before sacking Patrick Mahomes, the Raiders defensive lineman sat in his team hotel room, under quarantine. He turned on his phone, logged into FaceTime and watched alone as friends and family mourned the loss of the person who meant the most to him.

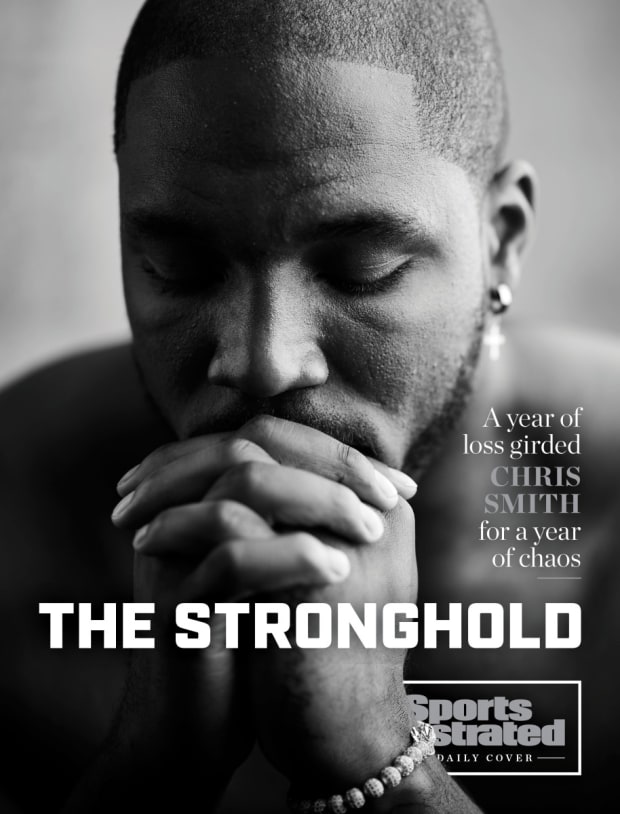

As his flight climbed toward the heavens on Sept. 11, as his teammates busied themselves with banal entertainment for the long plane ride to Carolina in Week 1, Chris Smith reclined in his seat and reflected on loss. Man, it’s crazy, the Raiders defensive lineman thought. It’s really been a year.

He considered how much had changed in her absence, how many moments she’d missed by his side. The peaks and valleys of his NFL career, now on his fifth team in seven seasons. The thrills and challenges of raising an infant daughter, Haven, now walking up a storm back home. The birthday celebrations, the new business, the isolation of a global pandemic …

But he’d also learned to grieve by remembering the good times, so that’s what he tried to do. He scrolled through old pictures and videos. He called up saved text messages. He listened to her music, including her absolute favorite song, “No Guidance” by Chris Brown and Drake.

“Just thinking about everything,” Smith, 28, says—but more than anything, he thought about their final hours together. About the images that replayed in his mind, like a tragic inflight movie. About, as he puts it, “what happened that night.”

***

One year earlier, on Tuesday, Sept. 10, 2019, Smith and his girlfriend, 26-year-old Petara Cordero (PJ, to close friends), went to dinner in Cleveland, where he spent most of last season with the Browns. At first they’d picked a restaurant within walking distance of Smith’s house, but they called an audible, driving to a hookah lounge instead.

The idea was to give Cordero a break—a casual evening out, just the two of them, while their nanny watched over four-week-old Haven. Still the couple rolled out in style: him behind the wheel of a new Lamborghini SUV; her wearing a Rolex and diamond heart necklace that he’d given her, plus her favorite black-white-and-red Jordan 1s. She was a big sneaker head, Smith says.

At the lounge, Smith and Cordero ordered drinks, picked out their favorite shisha flavors (mint, watermelon, strawberry) and eased into a conversation that escalated in seriousness, from their offseason travel plans (Smith lobbied for London, which he’d visited three times for NFL games) to their goals in raising Haven and their shared desire to someday marry. Three hours later, Smith realized he’d taken only a few sips of wine, such was his focus. “I knew right there, our love was going to go to another level,” he says.

The details of their ride home would soon be the subject of countless headlines, plus a somber interview segment preceding ESPN’s Browns-Jets broadcast the following Monday night. “Everyone knows the story,” Smith says. But here’s what sticks with him:

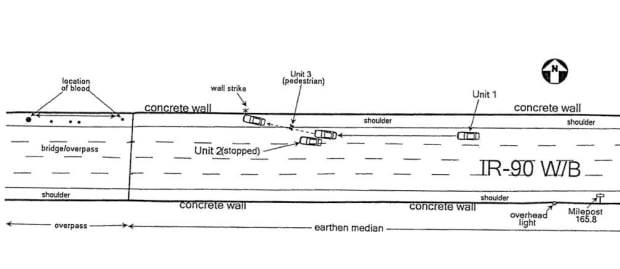

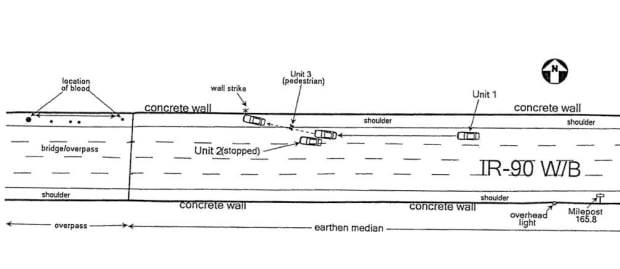

As 2 a.m. neared on Sept. 11, the couple was heading westbound on I-90—Smith estimates that he was driving 10 to 15 mph over the speed limit; one witness told police it was faster—when Smith struck something and blew a tire, causing his SUV to spin out and strike a concrete wall along the side of the road before coming to a stop in the far-right lane of a four-lane highway. The airbags deployed. The car was totaled. But neither he nor Cordero had sustained even a scratch. “I’m thinking, That’s a miracle,” Smith says. “Next thing you know… .”

Smith says he had moved into the passenger seat, still inside the car, and was rooting around for his cellphone with his head down and the passenger door ajar. She had stepped onto the shoulder, surveying the damage and dialing a friend for help. “Then I heard this bang,” he says.

Rushing out of the car, heart racing, Smith frantically scanned the shoulder for the source of the noise. In the moment, he didn’t notice that the passenger door had been destroyed, nearly plowed clean off. Nor did he spot the gray Mazda 3 in the distance, wrecked against the concrete wall. Nor, for that matter, could he see his girlfriend. Only later, after a detective showed him pictures of the scene, did he fully piece together what had happened.

The only thing he could make out, right in front of him on the asphalt, was a single Air Jordan sneaker.

***

They met toward the end of 2014, the same year Smith was drafted in the fifth round by Jacksonville, through Cordero’s older sister, Kyphi. But Cordero was living in Charlotte, near where Smith had grown up, and Smith was playing for the Jaguars. The distance made it tough to forge a friendship, let alone any kind of romantic bond.

Still they stayed in touch, growing closer with each text and call. After Smith learned in 2015 that his second child was on the way (with a mother who lives in Arkansas, after fathering a daughter with a separate woman in college), Cordero was one of the first people he told outside of his family. “She got a little upset,” Smith says, “like: ‘Chris, you don’t need to be having more kids.’ But … I respected her so much as a friend that I could tell her anything.”

Finally they began dating, in late 2017. Smith had been traded months earlier to Cincinnati, where then he played in every game of his expiring rookie contract. When the season ended, the free agent went back to Charlotte with nothing but free time. And as he got to know Cordero, he found there was so much to love.

Not just her beauty or her smile or her “corny, high-pitched laugh” that always turned heads. But also how her innate skepticism balanced out his constant sunny-day disposition. How she spoke up whenever she saw someone being treated unfairly. How she seemed to walk through life with an ironclad resolve, captured by a cursive tattoo on the right side of her chest, just below the collarbone: STAY STRONG.

More than anything, though, Smith recalls being taken by how her “spirit” made him feel. “She was very loyal, caring, genuine,” he says. “It wasn’t, I’m dating Chris, the NFL Player. It was, I like Chris as an actual person.” When he was away for football, she was the voice who greeted him on the phone each morning before he went to practice, and the last he heard at night as they fell asleep over FaceTime. When they were together, she was the partner with whom he sipped wine and danced to R&B music. Football, in fact, was only a very small part of their relationship. Cordero saw Smith play in person just twice: in the Browns’ season opener against the Titans last September; and in a pre-Christmas game against the Bengals, a year earlier. It was just days before that 2018 game that Chris and Petara received some of the happiest news of their lives.

While Smith was enjoying the early fruits of a three-year, $12 million deal with Cleveland, Cordero learned she was expecting. They found a nanny and bought six months’ worth of diapers. They traveled to Hawaii and Puerto Rico on babymoons, strolling the beaches and sampling every restaurant, mapping out their future as three. Eventually, at a gender reveal party, Cordero broke out Smith’s sack dance, a two-handed belly rub, as firecrackers shot pink flares. “It was just a perfect story,” Smith says. “It was like no bad could happen.”

The following August, only hours after Smith arrived back in Charlotte from a joint training camp practice against the Colts, Cordero went into labor. “She dilated to nine centimeters and she didn’t use an epidural until the end,” Smith says. “It just shows how tough she was.” When it came time to name their daughter, Cordero stood strong again. “She said, ‘You get the last name, so let me choose the first!’ ”

Fourteen months later, Smith says he isn’t exactly sure how Cordero landed on Haven. But he knows what the name means to him now. “I correlate it to my grieving process,” he says. “Haven means a safe place. After Petara passed, [our daughter] was my safe haven.”

***

After the bang, everything was a blur.

The walk down the shoulder of the highway, some 60 yards beyond the SUV, until he found where her body had landed, still wearing her jewelry, but only one shoe. The ambulance ride from the scene, during which his pleas to EMTs—“Is she going to be okay? Is she going to be okay?”—were met by telling silence. The sobriety test administered by police at the hospital. (He passed, having barely drank any wine.) And finally the doctor’s conclusive words: Cordero had almost certainly died on impact when a passing vehicle—driven by a 47-year-old woman who later told police that she had been distracted by a bug in her car—struck Cordero on the side of the road. “She didn’t feel any pain,” Smith says. “It was like she died in her sleep.”

For Smith, the anguish didn’t fully sink in until he returned home from the hospital, broke the news to family, and then walked down the block to a neighbor’s house. “Baker Mayfield stayed two doors down,” Smith says. “I fell into his arms, crying.”

“Anything you need,” Mayfield replied. “I got you.”

The next few days were the toughest. While a steady parade of Browns players, coaches and officials stopped by Smith’s house, bringing meals and gifts and sympathies, Smith was trapped in a fog of grief. He relived the events over and over in his mind, second-guessing every decision. What if we’d gone to the closer restaurant? What if… . He considered how close the other car had come to hitting him, too. I shouldn’t be here today.

He awoke in tears each morning, “bawling," he says. He didn’t eat; he drank only water and lost close to 10 pounds. He considered his football future. “At first,” he says, “I didn’t want to play no more.”

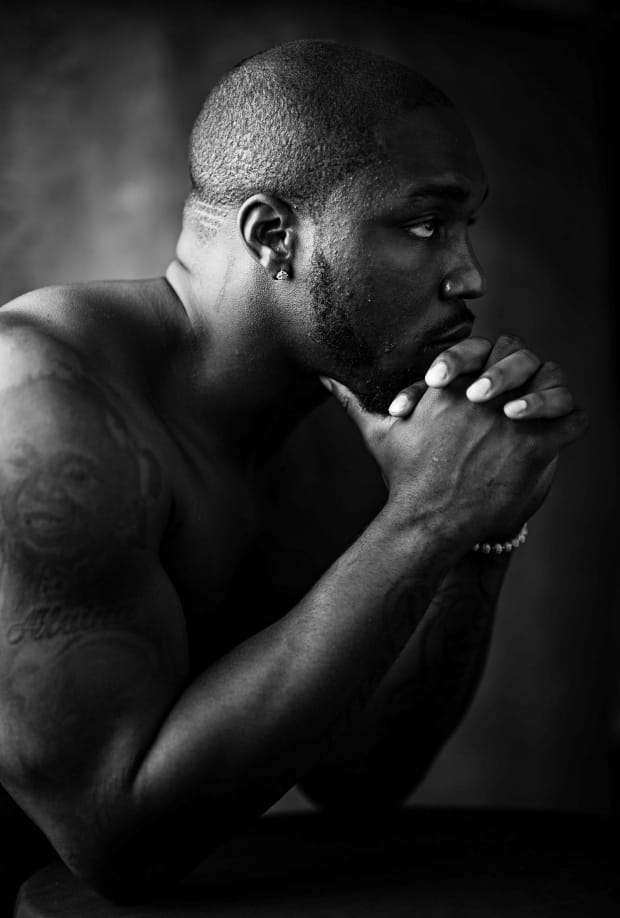

Over time, though, Smith came to terms with his loss. He took comfort in the nap that he and Cordero had taken together, alongside Haven, before dinner that night; in the shisha they’d shared; in their talk at the hookah lounge. He drew happiness from the memory of seeing her in the stands during the season opener. And he found solace in the new tattoo on his right forearm, which he (and some of Cordero’s family and friends) had inked in her honor, to match the one below her collarbone: STAY STRONG.

So it was that on that Saturday, three days after Cordero’s death, Smith, accompanied by a few of Cordero’s relatives, returned to practice. The Browns had told him to take all the time off that he needed, Smith says, but he’d longed for the familiarity of work. “My teammates lifted me up.”

The twin bedrocks of family and football continued to prop up Smith heading into that Monday night’s game against the Jets. He served as a pregame captain, walking out for the coin toss, and played 26 snaps in a 23-3 romp, deflecting a pass along the way. But his mind was far from the game. “I was there, but I wasn’t,” he says. “All I could think about was: Man, she’s really gone.”

***

If returning to the field provided an escape, then the following week brought a never-ending blitz of reminders about reality: a candlelight vigil, body viewings, funeral arrangements and, finally, a “homegoing” service, as the announcement called it, in Charlotte. Smith, a lifelong drummer, played gospel songs with his family’s band and gave a speech, drawing on lessons learned from his pastor mother and deacon father. “I know she’s in a better place,” he told the crowd. “When I’m dead, save me a spot in the bed so we can watch Netflix.”

For Smith, there have since been plenty of trying moments. He missed her support when the Browns cut him last December (in a decision that then-coach Freddie Kitchens described as "even more difficult" because of the circumstances)… and when the Panthers did the same in July. (Having signed on March 5, just before the coronavirus outbreak, he never even entered Carolina’s facility.) When the former team released him, he says, “I looked at God, like: I don't know what you’re doing—but you got me through this situation with Petara ... you’re going to bring me through this.” And on the night before the anniversary of her death, as he drove to meet some new Raiders teammates for dinner in Las Vegas and found himself anxiously gripping the wheel, replaying the crash in his mind, he sure could’ve used that old, steadying presence.

At every turn, though, Smith has managed his sorrow by surrounding himself with familiar faces. Javon Hargrave, a friend from high school who signed this offseason with the Eagles, drove from Pittsburgh to visit shortly after the crash. Linebacker Christian Kirksey, an old teammate from the Browns, shared with him the pain of losing his own father to a heart attack, when Kirksey was 17. And Smith tries to call Cordero’s family at least once a day, including her mother, Denise, who he told early on, “The only way we’re going to get through this is by sticking together.”

Earlier this summer, on what would have been Petara’s 27th birthday, Smith and her family gathered for an intimate party at a house by a lake, where a buffet spread offered her favorite Peruvian rotisserie chicken and a saxophonist played “No Guidance.” Guests wore facial coverings that read PETARA FOREVER and released balloons into the summer sky, near a display of lights spelling out HAPPY BIRTHDAY PJ. Smith cheered himself up that afternoon by thinking about how Cordero would’ve loved to relax down by the lake if she’d been there—and how she “would’ve hated that I was a little late.” At the end of the night, he pulled out a new pair of Jordan 1s and placed them in a glass case, which he planned to display in Haven’s room.

A similarly bittersweet celebration on the evening of Sept. 11 marked the anniversary of Cordero’s death. A dozen or so friends and family met at her old apartment in Charlotte, but Smith was unable to experience this moment in person because of the NFL's coronavirus travel protocol. Quarantining at the Raiders’ team hotel only a few miles away before their Week 1 game against the Panthers, he watched the festivities from his room, on FaceTime, telling the small crowd: “We made it through a year. I know the days aren’t going to get easier, but we’ve got to keep on keeping on.”

***

Everyone copes with loss in different ways. Smith says he was never angry—not at the world, not at himself, not even at the other driver. (While Smith was found guilty of a minor traffic misdemeanor for his single-car crash, the woman in the Mazda saw no criminal charges; she admitted to drinking before getting behind the wheel, but police determined that she hadn’t crossed the legal threshold.) “There should’ve been consequences,” Smith says. “But no matter the consequence, it’s not going to bring Petara back. So we’ve got to live her memory each day.”

For him, grief is not about letting go. Rather, he holds tighter to those things that keep Cordero around. Her old shoes and dresses—any clothing Haven might some day wear—“I keep all that stuff,” Smith says. Videos. Text messages. Her final Instagram post, from last September, in which Smith towers over her, leaning down for a kiss, with the caption: “This a forever thing, I love you through everything. ❤️” Smith has even found himself taking more pictures than he used to, trying to capture as many moments as possible.

She’s there in other forms too. In the pink lock box in Haven’s bedroom that contains a heart-shaped necklace holding a pinch of her mother’s ashes. In Smith’s plans for a Charlotte-area hookah lounge, Cloud, which he and Petara’s sister, Kyphi, aim to launch next month. (A yet-to-be-determined shisha flavor will be named after Cordero, Smith says, and guests who bring a picture of a lost loved one will get a free drink each visit.)

He’s also carrying her legacy into his work as a spokesman for Emergency Safety Solutions, a tech company that seeks to equip cars with “emergency mode” hazard lights that flash 2.5 times faster than the standard (which was established 70-odd years ago). Between 2016 and ’18, according to government data, more than 14,000 people were injured each year in accidents involving “stationary and disabled vehicles,” resulting in upwards of 560 annual deaths. Smith wonders how many of those lives could have been saved. “If I had those [faster] hazard lights,” Smith guesses, “Haven would still have a mom.”

Nowhere does he feel PJ’s presence more than around that one-year-old daughter, who he says looks and acts just like her mother, from her skepticism (“[Petara] had to see what type of person you were before she actually engaged”) to her smarts. Not long ago, Smith proudly reports, Haven gestured toward a picture of Cordero and said, “Mommy.”

Haven is spending this NFL season in Charlotte with her mother’s family now that her father is playing for Las Vegas, having inked a one-year deal in late August. Smith points out that he also drew interest from the Chargers and the Lions after the Panthers cut him, but the possibility of reuniting with his old Bengals defensive coordinator, Paul Guenther, played a role in his choice. That and the lack of state income tax. And the Vegas weather. “Detroit’s not bad,” Smith says. “But Detroit [versus] Vegas? That ain’t even hard.”

After toiling on the Raiders' practice squad through the first four weeks of this season, Smith was activated for last Sunday’s 40-32 upset of the Chiefs, earning a postgame-speech shoutout from coach Jon Gruden for his two solo tackles against the defending champs, including his first sack since November of 2018. Naturally, Smith celebrated his takedown of Patrick Mahomes by rubbing his belly. Then he pointed to the sky. “To God,” he says. “And to her.” (After the sack, he fled to the Las Vegas sideline because, he says, “I was tired as hell.")

It was an afternoon of personal triumph for Smith, more than the limited-capacity crowd dotting Arrowhead Stadium could have possibly known. “What happened with me and PJ, people probably thought: He’s supposed to give up and quit football; he ain’t got it no more... Stuff like that,” Smith says. “Yesterday was a great way to [show] the world that I’m back.”

Then again, he has bounced around the league enough by now to know that one strong game does not guarantee a roster spot. There will be bumps in the road: the global pandemic, the Raiders’ next opponent, the challenges of living so far away from family… . But when those bumps come, Smith knows what to do—the same thing he does whenever his body aches during a particularly grueling practice, or whenever his eyes tear up on a particularly tough morning. He will read the words tattooed in cursive across the inside of his right forearm, just above the wrist, and he will remind himself to stay strong.

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories here

A few weeks before sacking Patrick Mahomes, the Raiders defensive lineman sat in his team hotel room, under quarantine. He turned on his phone, logged into FaceTime and watched alone as friends and family mourned the loss of the person who meant the most to him.

As his flight climbed toward the heavens on Sept. 11, as his teammates busied themselves with banal entertainment for the long plane ride to Carolina in Week 1, Chris Smith reclined in his seat and reflected on loss. Man, it’s crazy, the Raiders defensive lineman thought. It’s really been a year.

He considered how much had changed in her absence, how many moments she’d missed by his side. The peaks and valleys of his NFL career, now on his fifth team in seven seasons. The thrills and challenges of raising an infant daughter, Haven, now walking up a storm back home. The birthday celebrations, the new business, the isolation of a global pandemic …

But he’d also learned to grieve by remembering the good times, so that’s what he tried to do. He scrolled through old pictures and videos. He called up saved text messages. He listened to her music, including her absolute favorite song, “No Guidance” by Chris Brown and Drake.

“Just thinking about everything,” Smith, 28, says—but more than anything, he thought about their final hours together. About the images that replayed in his mind, like a tragic inflight movie. About, as he puts it, “what happened that night.”

***

One year earlier, on Tuesday, Sept. 10, 2019, Smith and his girlfriend, 26-year-old Petara Cordero (PJ, to close friends), went to dinner in Cleveland, where he spent most of last season with the Browns. At first they’d picked a restaurant within walking distance of Smith’s house, but they called an audible, driving to a hookah lounge instead.

The idea was to give Cordero a break—a casual evening out, just the two of them, while their nanny watched over four-week-old Haven. Still the couple rolled out in style: him behind the wheel of a new Lamborghini SUV; her wearing a Rolex and diamond heart necklace that he’d given her, plus her favorite black-white-and-red Jordan 1s. She was a big sneaker head, Smith says.

At the lounge, Smith and Cordero ordered drinks, picked out their favorite shisha flavors (mint, watermelon, strawberry) and eased into a conversation that escalated in seriousness, from their offseason travel plans (Smith lobbied for London, which he’d visited three times for NFL games) to their goals in raising Haven and their shared desire to someday marry. Three hours later, Smith realized he’d taken only a few sips of wine, such was his focus. “I knew right there, our love was going to go to another level,” he says.

The details of their ride home would soon be the subject of countless headlines, plus a somber interview segment preceding ESPN’s Browns-Jets broadcast the following Monday night. “Everyone knows the story,” Smith says. But here’s what sticks with him:

As 2 a.m. neared on Sept. 11, the couple was heading westbound on I-90—Smith estimates that he was driving 10 to 15 mph over the speed limit; one witness told police it was faster—when Smith struck something and blew a tire, causing his SUV to spin out and strike a concrete wall along the side of the road before coming to a stop in the far-right lane of a four-lane highway. The airbags deployed. The car was totaled. But neither he nor Cordero had sustained even a scratch. “I’m thinking, That’s a miracle,” Smith says. “Next thing you know… .”

Smith says he had moved into the passenger seat, still inside the car, and was rooting around for his cellphone with his head down and the passenger door ajar. She had stepped onto the shoulder, surveying the damage and dialing a friend for help. “Then I heard this bang,” he says.

Rushing out of the car, heart racing, Smith frantically scanned the shoulder for the source of the noise. In the moment, he didn’t notice that the passenger door had been destroyed, nearly plowed clean off. Nor did he spot the gray Mazda 3 in the distance, wrecked against the concrete wall. Nor, for that matter, could he see his girlfriend. Only later, after a detective showed him pictures of the scene, did he fully piece together what had happened.

The only thing he could make out, right in front of him on the asphalt, was a single Air Jordan sneaker.

***

They met toward the end of 2014, the same year Smith was drafted in the fifth round by Jacksonville, through Cordero’s older sister, Kyphi. But Cordero was living in Charlotte, near where Smith had grown up, and Smith was playing for the Jaguars. The distance made it tough to forge a friendship, let alone any kind of romantic bond.

Still they stayed in touch, growing closer with each text and call. After Smith learned in 2015 that his second child was on the way (with a mother who lives in Arkansas, after fathering a daughter with a separate woman in college), Cordero was one of the first people he told outside of his family. “She got a little upset,” Smith says, “like: ‘Chris, you don’t need to be having more kids.’ But … I respected her so much as a friend that I could tell her anything.”

Finally they began dating, in late 2017. Smith had been traded months earlier to Cincinnati, where then he played in every game of his expiring rookie contract. When the season ended, the free agent went back to Charlotte with nothing but free time. And as he got to know Cordero, he found there was so much to love.

Not just her beauty or her smile or her “corny, high-pitched laugh” that always turned heads. But also how her innate skepticism balanced out his constant sunny-day disposition. How she spoke up whenever she saw someone being treated unfairly. How she seemed to walk through life with an ironclad resolve, captured by a cursive tattoo on the right side of her chest, just below the collarbone: STAY STRONG.

More than anything, though, Smith recalls being taken by how her “spirit” made him feel. “She was very loyal, caring, genuine,” he says. “It wasn’t, I’m dating Chris, the NFL Player. It was, I like Chris as an actual person.” When he was away for football, she was the voice who greeted him on the phone each morning before he went to practice, and the last he heard at night as they fell asleep over FaceTime. When they were together, she was the partner with whom he sipped wine and danced to R&B music. Football, in fact, was only a very small part of their relationship. Cordero saw Smith play in person just twice: in the Browns’ season opener against the Titans last September; and in a pre-Christmas game against the Bengals, a year earlier. It was just days before that 2018 game that Chris and Petara received some of the happiest news of their lives.

While Smith was enjoying the early fruits of a three-year, $12 million deal with Cleveland, Cordero learned she was expecting. They found a nanny and bought six months’ worth of diapers. They traveled to Hawaii and Puerto Rico on babymoons, strolling the beaches and sampling every restaurant, mapping out their future as three. Eventually, at a gender reveal party, Cordero broke out Smith’s sack dance, a two-handed belly rub, as firecrackers shot pink flares. “It was just a perfect story,” Smith says. “It was like no bad could happen.”

The following August, only hours after Smith arrived back in Charlotte from a joint training camp practice against the Colts, Cordero went into labor. “She dilated to nine centimeters and she didn’t use an epidural until the end,” Smith says. “It just shows how tough she was.” When it came time to name their daughter, Cordero stood strong again. “She said, ‘You get the last name, so let me choose the first!’ ”

Fourteen months later, Smith says he isn’t exactly sure how Cordero landed on Haven. But he knows what the name means to him now. “I correlate it to my grieving process,” he says. “Haven means a safe place. After Petara passed, [our daughter] was my safe haven.”

***

After the bang, everything was a blur.

The walk down the shoulder of the highway, some 60 yards beyond the SUV, until he found where her body had landed, still wearing her jewelry, but only one shoe. The ambulance ride from the scene, during which his pleas to EMTs—“Is she going to be okay? Is she going to be okay?”—were met by telling silence. The sobriety test administered by police at the hospital. (He passed, having barely drank any wine.) And finally the doctor’s conclusive words: Cordero had almost certainly died on impact when a passing vehicle—driven by a 47-year-old woman who later told police that she had been distracted by a bug in her car—struck Cordero on the side of the road. “She didn’t feel any pain,” Smith says. “It was like she died in her sleep.”

For Smith, the anguish didn’t fully sink in until he returned home from the hospital, broke the news to family, and then walked down the block to a neighbor’s house. “Baker Mayfield stayed two doors down,” Smith says. “I fell into his arms, crying.”

“Anything you need,” Mayfield replied. “I got you.”

The next few days were the toughest. While a steady parade of Browns players, coaches and officials stopped by Smith’s house, bringing meals and gifts and sympathies, Smith was trapped in a fog of grief. He relived the events over and over in his mind, second-guessing every decision. What if we’d gone to the closer restaurant? What if… . He considered how close the other car had come to hitting him, too. I shouldn’t be here today.

He awoke in tears each morning, “bawling," he says. He didn’t eat; he drank only water and lost close to 10 pounds. He considered his football future. “At first,” he says, “I didn’t want to play no more.”

Over time, though, Smith came to terms with his loss. He took comfort in the nap that he and Cordero had taken together, alongside Haven, before dinner that night; in the shisha they’d shared; in their talk at the hookah lounge. He drew happiness from the memory of seeing her in the stands during the season opener. And he found solace in the new tattoo on his right forearm, which he (and some of Cordero’s family and friends) had inked in her honor, to match the one below her collarbone: STAY STRONG.

So it was that on that Saturday, three days after Cordero’s death, Smith, accompanied by a few of Cordero’s relatives, returned to practice. The Browns had told him to take all the time off that he needed, Smith says, but he’d longed for the familiarity of work. “My teammates lifted me up.”

The twin bedrocks of family and football continued to prop up Smith heading into that Monday night’s game against the Jets. He served as a pregame captain, walking out for the coin toss, and played 26 snaps in a 23-3 romp, deflecting a pass along the way. But his mind was far from the game. “I was there, but I wasn’t,” he says. “All I could think about was: Man, she’s really gone.”

***

If returning to the field provided an escape, then the following week brought a never-ending blitz of reminders about reality: a candlelight vigil, body viewings, funeral arrangements and, finally, a “homegoing” service, as the announcement called it, in Charlotte. Smith, a lifelong drummer, played gospel songs with his family’s band and gave a speech, drawing on lessons learned from his pastor mother and deacon father. “I know she’s in a better place,” he told the crowd. “When I’m dead, save me a spot in the bed so we can watch Netflix.”

For Smith, there have since been plenty of trying moments. He missed her support when the Browns cut him last December (in a decision that then-coach Freddie Kitchens described as "even more difficult" because of the circumstances)… and when the Panthers did the same in July. (Having signed on March 5, just before the coronavirus outbreak, he never even entered Carolina’s facility.) When the former team released him, he says, “I looked at God, like: I don't know what you’re doing—but you got me through this situation with Petara ... you’re going to bring me through this.” And on the night before the anniversary of her death, as he drove to meet some new Raiders teammates for dinner in Las Vegas and found himself anxiously gripping the wheel, replaying the crash in his mind, he sure could’ve used that old, steadying presence.

At every turn, though, Smith has managed his sorrow by surrounding himself with familiar faces. Javon Hargrave, a friend from high school who signed this offseason with the Eagles, drove from Pittsburgh to visit shortly after the crash. Linebacker Christian Kirksey, an old teammate from the Browns, shared with him the pain of losing his own father to a heart attack, when Kirksey was 17. And Smith tries to call Cordero’s family at least once a day, including her mother, Denise, who he told early on, “The only way we’re going to get through this is by sticking together.”

Earlier this summer, on what would have been Petara’s 27th birthday, Smith and her family gathered for an intimate party at a house by a lake, where a buffet spread offered her favorite Peruvian rotisserie chicken and a saxophonist played “No Guidance.” Guests wore facial coverings that read PETARA FOREVER and released balloons into the summer sky, near a display of lights spelling out HAPPY BIRTHDAY PJ. Smith cheered himself up that afternoon by thinking about how Cordero would’ve loved to relax down by the lake if she’d been there—and how she “would’ve hated that I was a little late.” At the end of the night, he pulled out a new pair of Jordan 1s and placed them in a glass case, which he planned to display in Haven’s room.

A similarly bittersweet celebration on the evening of Sept. 11 marked the anniversary of Cordero’s death. A dozen or so friends and family met at her old apartment in Charlotte, but Smith was unable to experience this moment in person because of the NFL's coronavirus travel protocol. Quarantining at the Raiders’ team hotel only a few miles away before their Week 1 game against the Panthers, he watched the festivities from his room, on FaceTime, telling the small crowd: “We made it through a year. I know the days aren’t going to get easier, but we’ve got to keep on keeping on.”

***

Everyone copes with loss in different ways. Smith says he was never angry—not at the world, not at himself, not even at the other driver. (While Smith was found guilty of a minor traffic misdemeanor for his single-car crash, the woman in the Mazda saw no criminal charges; she admitted to drinking before getting behind the wheel, but police determined that she hadn’t crossed the legal threshold.) “There should’ve been consequences,” Smith says. “But no matter the consequence, it’s not going to bring Petara back. So we’ve got to live her memory each day.”

For him, grief is not about letting go. Rather, he holds tighter to those things that keep Cordero around. Her old shoes and dresses—any clothing Haven might some day wear—“I keep all that stuff,” Smith says. Videos. Text messages. Her final Instagram post, from last September, in which Smith towers over her, leaning down for a kiss, with the caption: “This a forever thing, I love you through everything. ❤️” Smith has even found himself taking more pictures than he used to, trying to capture as many moments as possible.

She’s there in other forms too. In the pink lock box in Haven’s bedroom that contains a heart-shaped necklace holding a pinch of her mother’s ashes. In Smith’s plans for a Charlotte-area hookah lounge, Cloud, which he and Petara’s sister, Kyphi, aim to launch next month. (A yet-to-be-determined shisha flavor will be named after Cordero, Smith says, and guests who bring a picture of a lost loved one will get a free drink each visit.)

He’s also carrying her legacy into his work as a spokesman for Emergency Safety Solutions, a tech company that seeks to equip cars with “emergency mode” hazard lights that flash 2.5 times faster than the standard (which was established 70-odd years ago). Between 2016 and ’18, according to government data, more than 14,000 people were injured each year in accidents involving “stationary and disabled vehicles,” resulting in upwards of 560 annual deaths. Smith wonders how many of those lives could have been saved. “If I had those [faster] hazard lights,” Smith guesses, “Haven would still have a mom.”

Nowhere does he feel PJ’s presence more than around that one-year-old daughter, who he says looks and acts just like her mother, from her skepticism (“[Petara] had to see what type of person you were before she actually engaged”) to her smarts. Not long ago, Smith proudly reports, Haven gestured toward a picture of Cordero and said, “Mommy.”

Haven is spending this NFL season in Charlotte with her mother’s family now that her father is playing for Las Vegas, having inked a one-year deal in late August. Smith points out that he also drew interest from the Chargers and the Lions after the Panthers cut him, but the possibility of reuniting with his old Bengals defensive coordinator, Paul Guenther, played a role in his choice. That and the lack of state income tax. And the Vegas weather. “Detroit’s not bad,” Smith says. “But Detroit [versus] Vegas? That ain’t even hard.”

After toiling on the Raiders' practice squad through the first four weeks of this season, Smith was activated for last Sunday’s 40-32 upset of the Chiefs, earning a postgame-speech shoutout from coach Jon Gruden for his two solo tackles against the defending champs, including his first sack since November of 2018. Naturally, Smith celebrated his takedown of Patrick Mahomes by rubbing his belly. Then he pointed to the sky. “To God,” he says. “And to her.” (After the sack, he fled to the Las Vegas sideline because, he says, “I was tired as hell.")

It was an afternoon of personal triumph for Smith, more than the limited-capacity crowd dotting Arrowhead Stadium could have possibly known. “What happened with me and PJ, people probably thought: He’s supposed to give up and quit football; he ain’t got it no more... Stuff like that,” Smith says. “Yesterday was a great way to [show] the world that I’m back.”

Then again, he has bounced around the league enough by now to know that one strong game does not guarantee a roster spot. There will be bumps in the road: the global pandemic, the Raiders’ next opponent, the challenges of living so far away from family… . But when those bumps come, Smith knows what to do—the same thing he does whenever his body aches during a particularly grueling practice, or whenever his eyes tear up on a particularly tough morning. He will read the words tattooed in cursive across the inside of his right forearm, just above the wrist, and he will remind himself to stay strong.

0 Comments