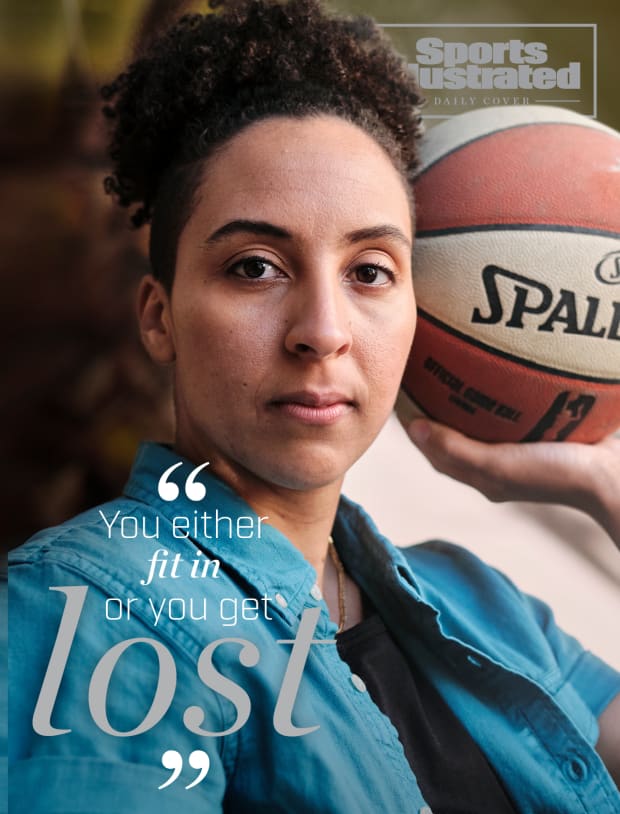

Trans athletes have become political lightning rods, but in a sex-segregated sports world, where do nonbinary people like Layshia Clarendon fit in?

It was in the WNBA bubble—the Wubble—that New York Liberty guard Layshia Clarendon made the decision. The Wubble was a stressful experience for Clarendon. For one, they were living through a pandemic. For another, life at the IMG Academy in Bradenton, Fla., was very small. Clarendon shuffled among their villa, the gym and games, like Groundhog Day designed for a professional athlete. They had also left their pregnant wife at home. (Clarendon alternately uses she, he and they pronouns.)

In her little time off, Clarendon became the face—and the force—behind the WNBA’s Say Her Name campaign, thinking about and talking about Black death on a near constant basis, busy with calls and webinars and brainstorming sessions. It was important work, and Clarendon felt called to do it, but it was draining, too. And there was another stressor that was draining Clarendon, one he wasn’t posting about on social media or sharing in postgame interviews: He couldn’t stop thinking about his chest.

Clarendon had no idea whether the WNBA would support their decision to have top surgery, a gender affirmation procedure that removes a person’s breasts and reshapes their chest to be flat, but they knew they would have the surgery regardless of how the league responded. The medical decision was not the struggle for Clarendon; the challenge was in figuring out whether she would be accepted by a sports world that was not designed for nonbinary trans people like her; she’d quietly updated the pronouns in her Twitter bio over the summer, but this was something different altogether. In the binary world of sports, leagues exist for men and for women. Clarendon sometimes feels like both of those things and other times feels like neither.

“It was something for me that was causing a lot of mental health issues,” Clarendon, 29, says of the worry about whether to move forward with top surgery and whether the WNBA would allow it—and what it would mean for his career if the league didn’t. “It made being in the bubble even harder than it [already] was.” It opened up a whole slate of questions that she had to consider, so after the season was over, she went to Terri Jackson, the executive director of the Women’s National Basketball Players Association (WNBPA). There was no precedent for this, but Jackson was all in to support Clarendon.

It’s generally considered bad form to focus on the particulars of trans people’s bodies, but as a professional athlete, the decisions Clarendon—or any trans athlete—makes about their body are incredibly consequential. Careers can hinge on them. The questions Clarendon considered included: What will the recovery look like and how will it impact my 2021 season? The league and my team have a right to know a lot about my body because it affects my play, but is there anything personal that the league can’t ask me about? I know I am going to publicly talk about my top surgery, but what if another player has top or bottom surgery and doesn’t want to share that with their team or the public? If the league doesn’t support me, can I be fired?

When I first spoke to Clarendon in December, a few weeks before their surgery, they were still trying to navigate these conversations with the WNBA. Luckily, they received the “full support” of commissioner Cathy Engelbert, as well as the Liberty and the WNBPA. On Jan. 29, the day that Clarendon announced her surgery on social media, coordinated statements went out from each of the league accounts, too.

It was a stark contrast to how the National Women’s Soccer League responded when Quinn, a midfielder for the OL Reign, came out as nonbinary and transgender

on Instagram in September 2020.“I wanted to make sure that my identity was represented in my workplace, and in the public sphere,” Quinn, 25, says now of the decision to post about their identity on social media. Their teammates and coach knew, but the public did not, which meant that Quinn had to deal with being misgendered in the press—having the wrong pronouns used—and feeling invisible on a daily basis. “I really wanted to be another visible person in the sports realm, especially playing at such a high level. I wanted to help others that were looking for people like themselves in sport.”

Quinn’s Instagram post made headlines. But while their announcement was met mostly with support from the public, the NWSL's official Twitter account took weeks to acknowledge the event, and the Reign’s account took even longer. When the NWSL finally did acknowledge it, it was a quote tweet of the BBC’s coverage of Quinn’s coming out. In Quinn’s first televised game after coming out, broadcasters got their pronouns wrong on-air.

The way the NWSL lacked explicit public support for Quinn after they came out was likely not ill-intentioned (the NWSL did not respond to multiple requests for comment). In the Reign’s case, the team did what it thought was most supportive of Quinn.

“Quinn privately shared their plans with the club prior to their public announcement. We believed this was Quinn’s information to disclose in whatever way they felt was right, and at whatever time they felt was appropriate,” Reign CEO Bill Predmore told Sports Illustrated via email. “While we were available to provide support if requested, the club was not involved in the form or timing of the announcement. Our view was that this was the most personal of news to share, so unless our support was specifically requested by Quinn, we should not impose our perspective to help shape the message nor should our club serve as the messenger.”

But it is an example of how unprepared most sports leagues are to support nonbinary athletes. The WNBA supported Clarendon as well as it did only because Clarendon advocated for themself behind the scenes for months. Quinn and Clarendon, alongside triathlete Rach McBride, are likely the only openly nonbinary athletes competing professionally in North American sports. But the number of out nonbinary athletes is only going to increase.

Trans athletes have become political lightning rods and targets of institutionalized oppression; already this year Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi have passed laws that purport to, in the words of Tennessee Governor Bill Lee, “preserve women’s athletics and ensure fair competition.” The focus on physiology and biology and arguments about “protecting women” predominantly impact transfeminine athletes and take away the humanity from people who just want to play the sports they love. In the highly gendered world of sport, it’s binary trans people—trans women and trans men—who are most visibly fighting for their right to compete. But left out of that conversation altogether are nonbinary athletes, who do not identify with a binary gender.

“People’s education level on trans people in general is extremely low,” says Ashland Johnson, the president and founder of the Inclusion Playbook, an advocacy group working to bring about social change through sports. “When it comes to nonbinary people, it’s sometimes nonexistent.”

The existence of nonbinary people complicates a seemingly neat and tidy way of organizing athletics: men’s sports and women’s sports. Including nonbinary folks in the conversation requires a willingness to acknowledge that the way we currently categorize athletics is in need of an overhaul, and that leagues need to make accommodations for the nonbinary athletes who are already here.

The concept of nonbinary gender identity is not simply a third gender category. Rather, nonbinary identity sees gender as a spectrum: A person can exist anywhere in between the binary genders or shatter the binary altogether. “Nonbinary” can mean neither man nor woman. It can mean both man and woman. It can mean a million other things in between, each personal to the individual.

Nonbinary people can be assigned female at birth (AFAB) or assigned male at birth (AMAB). They can be intersex—a term used to describe someone who is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn't fit neatly into the boxes of “female” or “male” as the categories are typically defined. Nonbinary people can choose aspects of medical transition for themselves, like feminizing or masculinizing hormones or gender-affirmation surgeries, or they might not medically transition at all.

“I've always known I was more than just a girl or a woman, but I didn’t know what exactly I was,” says Clarendon. “And so, identifying as nonbinary and trans in terms of the larger umbrella is really important to me. That gives me a place to belong and gives me community.”

“Nonbinary” gives Clarendon a word to identify with, one that encapsulates the fact that they feel like they are “equally both,” sometimes more male, sometimes more female, but definitely much bigger than “woman.” “It’s really important to me for that to be seen and for me to be whole,” he says. “My gender is just too big to fit in either box.”

Sports gave Clarendon the freedom to be herself even before she had the words to articulate her gender. As a kid growing up in San Bernadino, Calif., he didn’t know what transgender or nonbinary was; all he knew was that he felt best when he was in his hoops clothes.

They didn’t necessarily talk about gender with their teammates, but they knew there were people like them in sports, who liked to dress in gender nonconforming ways like they did. “That feeling of belonging is invaluable as a young person,” Clarendon says. “I loved the competitiveness of sports, chasing a goal, the camaraderie of being around teammates and how when I made a pass to someone and they scored it felt like we could accomplish anything.”

Clarendon says that realizing that gender could be fluid and ever-evolving was life-changing. He first identified publicly as “non-cisgender” in an article for The Players’ Tribune in 2015. But it took longer for them to embrace the idea that they belonged under the trans umbrella, requiring them to unpack some of their own internalized transphobia and seeing trans identity beyond the singular, dominant narrative of transitioning from one binary gender to the other. Last summer, during the WNBA season, she told teammates that she was changing her pronouns, and she quietly updated them in his Twitter bio.

McBride’s process was a gradual one, too. Growing up in Tacoma, Wash., and later, Germany, they dropped hints to loved ones for over a decade that they had what they call “gender struggles.” They first heard the term “genderqueer”—another term that describes someone whose gender lives outside the binary and can sometimes be used interchangeably with nonbinary—in their 20s and instinctively knew that was what they were, but didn’t hear much about that identity outside of classes at the University of Ottawa. They didn’t find another word to describe themselves, though, until about two years ago when they began exploring nonbinary identity and started talking publicly about it on social media before coming out in a 2020 story in Triathlete magazine. Last year, at 42, the Vancouver resident switched to exclusively using they/them pronouns.

McBride—known as the “Purple Tiger”—has been racing full-time as a triathlete since 2011 and was dubbed “the most interesting [person] in triathlon” by TRS Radio. They are a three-time Ironman 70.3 champion, have logged eight Ironman 70.3 fastest bike splits and are a two-time Ironman bike course record holder and a three-time course record holder—including the Canadian National Championships. But not being able to fully embody their true self during competitions made them feel like they weren’t reaching their full potential.

“Just recognizing my gender identity has created a space for me to feel more comfortable at the start line, because my experience before was of feeling odd and like I didn’t fit in and I didn’t understand why,” says McBride. “Now, I understand why and I can embrace that and I can still compete amongst the people I feel most comfortable with.”

As society’s understanding of gender shifts and more and more athletes come out as nonbinary, leagues need to be prepared to accept them—not just in words, but with concrete policies. Most professional sports leagues in the United States do not have trans-inclusion policies, though that is beginning to change. The National Women’s Hockey League, the first league to adopt one, created theirs out of necessity when Buffalo Beauts player Harrison Browne socially transitioned in 2016. The National Women’s Soccer League and Athletes Unlimited both unveiled theirs in March.

Interestingly, the leagues we currently think of as men’s leagues are actually more inclusive of trans and nonbinary athletes from a strictly rules-based perspective. MLB, the NHL, the NBA, the NFL and MLS do not have gender requirements for participants; anyone is eligible to play in those leagues. These leagues might need “to make sure [their] locker room culture is welcoming,” as one league employee put it, but they wouldn’t have to change any rules to allow trans or nonbinary athletes to play.

Therefore, it’s women’s leagues that will have to take a hard look at their existing policies. At the time these leagues were formed, trans and nonbinary athletes weren’t on their radar. But allowing anyone who is marginalized by gender to play in the women’s leagues stays true to their original goal: to provide opportunities for people who were being systematically shut out of professional sports.

It’s something that women’s leagues are beginning to think critically about. “Quinn’s announcement showed us that we have some work to do (both as a club and as a league) to reconcile a league that has been primarily defined by gender with the reality that the definition no longer reflects the full range of individuals who are playing in our league,” says Predmore. “I am optimistic that we’ll find a new and better way to define our league in a manner that doesn’t rely on gender, but instead is focused on the quality of the players, our values and the experience we provide to fans.”

For AFAB athletes who aren’t taking masculinizing hormones, women’s leagues currently allow them to stay—Quinn, Clarendon and McBride are examples of that. But even that can be thorny. For example, they have to deal with being misgendered every day just by nature of being in a women’s league. It also seemingly lumps them into the category of “woman-lite,” when they’re not.

There is no current equivalent out athlete for AMAB nonbinary people in men’s leagues. “Sport is not safe for trans people, and it’s certainly not safe for people in men’s sports who do not perform a certain type of masculinity,” says Chris Mosier, the first trans man to qualify for the U.S. duathlon team and the founder of TransAthlete.com. “There is a structure in sport that probably prevents AMAB nonbinary people from [openly] participating.”

As more leagues establish trans-inclusion policies, they are likely to look to existing policies for guidance. But experts say these policies are not as inclusive as they may first appear. To understand why, we must first talk about testosterone.

There is a long history of sex testing in sports, often under the guise of protecting cisgender women from men who might infiltrate their division and win, despite there being no evidence that has ever happened. Over the last century or so, sex testing has ranged from intrusive genital exams to chromosome testing to hormone testing focused on testosterone, which is currently considered the one true indicator of competitive advantage. This idea has come about regarding trans women’s desire to compete against other women, though research has shown that any “advantage” trans women may have gained through masculinizing puberty is not retained after one year of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with feminizing hormones like estrogen.

But testosterone is a hormone that occurs naturally at varying ranges, even in cisgender women. Despite the shaky (at best) science, the International Olympic Committee currently ascribes to a testosterone-based policy, as do the NCAA and many other elite sports governing bodies. These policies require that athletes competing in the women’s category have testosterone levels under a certain number. This can disproportionately subject Black and brown women, whose femininity is policed due to racist stereotyping, to challenges to “prove” their gender.

“There is no solid evidence for the 10 nanomoles per liter for this regulation,” says Katrina Karkazis, coauthor of the book Testosterone: An Unauthorized Biography. “It is an arbitrary threshold the IOC chose but cannot be explicitly tied to evidence of a performance difference based on T levels.”

The NWHL, NWSL and AU’s policies also center on testosterone. This is often missed in these conversations—how testosterone is being used to exclude not only transfeminine people, but transmasculine people, as well. AFAB players are able to stay in the NWHL and AU as long as they are not taking masculinizing hormones—testosterone—as part of their medical transition. (The NCAA has a similar policy.) It might be called a “trans-inclusion” policy, but “it’s inclusive in name only” says Karkazis. Testosterone, she explains, is “being instrumentalized towards a particular end. And that end is around exclusion.”

Harrison Browne’s experience makes that clear—he left the NWHL so he could start hormones. “Do I wish that I could still play, if I could play in the league right now?” Browne doesn’t hesitate. “Probably, yeah. I’m still healthy.”

And while Browne is a trans man and it could be argued that there were other reasons why a women’s league was not an acceptable place for him, what happens if the next AFAB player who wants to take testosterone to more fully embody their true gender is nonbinary and wants to remain in a women’s league?

“These are really important questions that I don’t think enough people are asking in enough different levels and positions,” says Clarendon. “Right now, you either fit in or you get lost. Like, you meet the NCAA or IOC standards that make you eligible to play on the men’s or women’s side, or you don’t. Or you transition and you get lost, forced to move on with your life and mourn the career you had playing the sport you were assigned at birth. What would be your hope?”

The NWSL policy differs from the other two in that it allows for a therapeutic use exemption (TUE) for AFAB players who are taking testosterone but whose levels remain “within the typical limits of women athletes,” which mimics the IOC standards. However, it does not explicitly allow for nonbinary players, despite having one currently playing in the league. (The NWSL did not return requests for comment about which advocacy groups it consulted regarding its policy.)

AU’s policy stands out from the others in that it does not specify a testosterone level for transfeminine athletes who want to compete on women’s teams, just that they must be taking testosterone-suppressing medication. This is a big win for trans women and AMAB nonbinary people looking to compete against women. It allows them to do so without policing what it means to be a woman, or forcing AMAB nonbinary people into the same standards women are held to, which could invalidate their gender identity. Mosier helped the AU draft its policy, and it’s a step forward.

However, like the NWSL and NWHL’s policies, AU’s shows how the IOC’s arbitrary guidelines are having a trickle-down effect that results in exclusion. “Our drug policy follows the IOC list of banned substances, which includes testosterone as a performing-enhancing drug,” a spokesperson for AU told Sports Illustrated. “Additionally, because our policy on transgender and nonbinary athletes is not based on testosterone levels, it would be very difficult to implement a policy that allows testosterone use.”

Not every AFAB nonbinary person will want to take testosterone. But some will. And it’s not just trans and nonbinary athletes impacted by these policies. Not only are T levels incredibly variable person-to-person and day-to-day, “there’s actually contrary evidence, meaning that sometimes it’s the people with the lower level who perform better,” says Karkazis. In other words, measuring someone’s testosterone levels alone won’t actually tell you anything about what their sports performance will look like. As they stand now, these policies will have the impact of potentially pushing out the very athletes the leagues currently claim to support, and that should be concerning to everyone.

Conversations about how sports should be organized are not new. There’s this idea that “the possibilities for the future are to maintain the fully sex-segregated system or to abolish it entirely,” says Elizabeth Sharrow, associate professor of public policy and history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and whose work focuses on equity, policy and Title IX. “But that is a false narrative.” A false binary, like gender itself. “We have the ability to imagine participatory or competitive structures in lots of different ways,” they explain. “But in order to do so we have to give up the notion that categorization for athletics is easy, or is most fair or justifiable when we base it on the question of sex.”

Proposed solutions involve classing sports more like wrestling—by weight class, or by height for a sport like basketball—than by gender (Nancy Leong explores some of these options in her 2017 paper “Against Women’s Sports”). These solutions are flawed, as well, but reimagining the way we think about sports in the first place will require blowing up everything we think we know about how they should look. Clarendon sees potential in widening the focus of women’s leagues to include all people marginalized by gender, in line with the original reason they were created, while Quinn imagines an inclusive space being one that explicitly celebrates the identities of everyone who plays. Until the entire concept of sex segregation is seen as no longer functioning, nonbinary athletes and those who advocate for them are forced to work within the existing systems to make them more inclusive of people they were not designed to include in the first place.

If leagues truly do want to make themselves places that allow athletes to be fully themselves, they need to create the space for them to do so. There are some changes that can be implemented tomorrow, like including a player’s pronouns on the team’s media guides, just like they do for name pronunciation or position. That simple act could have potentially avoided Quinn’s being misgendered on-air last fall, or McBride’s having the wrong pronouns used “almost 100 times” during a race broadcast, something that was incredibly demoralizing. “It’s just like little pinpricks, every single time I hear [the wrong pronoun],” McBride explains. “It’s like there’s just no effort given.”

Teams and leagues could also normalize social media and communications staffs asking players what pronouns they want used for them on their social platforms and whether they have a name they prefer to use other than their given name. Offering uniform or kit styles that better align with a player’s gender could be another option.

Browne says that when he came out, the NWHL’s press team was incredibly supportive, but he wishes they had created a list of questions that were off-limits for reporters. That would have saved Browne from being faced with intrusive questions about his body. And true inclusion may also require leagues to grapple with their names—potentially being willing to drop the word “women” to describe their athletes, since it’s not an accurate descriptor.

“The rigidity of sports goes against my identity, in that I find having an expansive gender very exciting,” says Quinn. “There’s ways that we are ‘supposed’ to perform gender, even in sports, like when it comes to our uniforms or the language that we use. And so those can be pretty restricting and can go against my identity.”

Those changes are likely to have a positive impact on the mental health of nonbinary athletes, something that would benefit their on-field performance, too. Surgeries are often considered necessary for something like an injury, because that impacts an athlete’s ability to perform. But for Clarendon, their top surgery was necessary, too, both for their emotional well-being off the court and their performance on it. Trying to compartmentalize their gender and their job was impossible.

“We’re [never talking about] how hard it was to have breasts and go to the pool in a swimsuit top and the dysphoria that you’re experiencing, and then how it affects your overall mental health,” says Clarendon. “I’m a big believer that the healthier athletes are, the healthier products and commodities they are. … Being a whole person makes you a better performer at the end of the day, which is what honestly coaches and owners are really worried about, because it’s the entertainment business.”

These strategies will also help the athletes who are not yet out, who haven’t even grappled with the question of their own gender identity because it feels impossible to do so when their job is on the line. “Segregated systems suppress even the possibility of self-exploration for a lot of athletes,” says Sharrow, “because it’s frightening to imagine losing something you love or that is actually your sources of income just because the structures that govern suggest your identity might be impossible.”

As it stands now, players who want to come out publicly are left to navigate the decision on their own. “I don’t believe Layshia is the only one; she is just the only one who is open about it,” says Terri Jackson, the executive director of the WNBPA. Without a formal support process, leagues are not equipped to have conversations with the press or address players’ identities on social media channels. This lack of institutional support and precedent likely prevents other players from coming out.

“There’s been so much talk about exclusion,” says Quinn. But those conversations distract from what they see as the real issue, which is getting back to the reason people—including, and maybe especially, nonbinary people—play sports: “because we love connecting with our bodies.”

One of the best parts for Quinn of being out publicly has been the new extended trans community that they’ve found as a result of sharing their truth openly. They began navigating their public identity largely on their own, though their Canadian national team has begun to have conversations about what a trans-inclusion policy could look like and the Reign has begun to be more publicly intentionally supportive. In February 2021, the team’s social media accounts posted a graphic advertising season tickets with an image of Quinn next to the text “They play here” and adding pronouns for every player and coach to their website. That, combined with the WNBA’s coordinated effort, is evidence of a shift. Life Time, a health and fitness company that runs athletic events, has implemented a third gender option, “nonbinary/genderqueer” for all in-person run and triathlon events for the remainder of 2021 and plans to offer it for their entire portfolio of events—both in-person and virtual—in 2022 and beyond.

But until sports as a whole are ready to have conversations about the ways in which they’re organized, relatively simple changes would allow players to fully embody their own identities and remain in the leagues they feel most comfortable. While Quinn and McBride say there are ways in which being in a women’s league sometimes rubs up uncomfortably against their gender, players like Clarendon, who says they “feel like both genders,” are perfectly at home in a women’s league, but are waiting for the league to catch up to them.

“I felt particularly proud [last] summer that it was a queer, nonbinary, Black person who was leading the social justice movement,” she says of her role on the W’s Social Justice Council. She just wishes the league would be ready to name that identity and own the totality of the identities under its umbrella. Because it’s not just a league of 144 women; Clarendon’s presence proves that. As vice president of the WNBPA and as one of the the oldest players on the Liberty’s young roster, he gets to be a voice for change and an example for the league’s next generation, one that is perhaps ready to talk openly about gender and identity among its players.

Clarendon is also entering the 2021 season with the freedom of being completely, fully, openly himself. They will no longer have the stress of wondering whether their league will accept them, whether they will have to fight for inclusion in a sport they have dedicated their life to. Even still, she knows these conversations are just beginning.

“There are only going to be more people who come out. We’ve been here the whole time,” Clarendon says. “My story is not that unique in that gender is an evolution. What is going to happen when Ryan Ruocco uses ‘he’ for me on a[n ESPN] broadcast? What if I go exclusively by ‘he’ tomorrow? Is the league ready for that?”

Britni de la Cretaz is a freelance writer whose work focuses on the intersections of sports, gender and culture. Their book, Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women's Football League, is forthcoming from Bold Type Books.

• The Faults in Our Tiny, Little Sports Stars

• The Unrivaled Arrival of Trevor Lawrence

• The Trade That Might Have Saved Caris LeVert

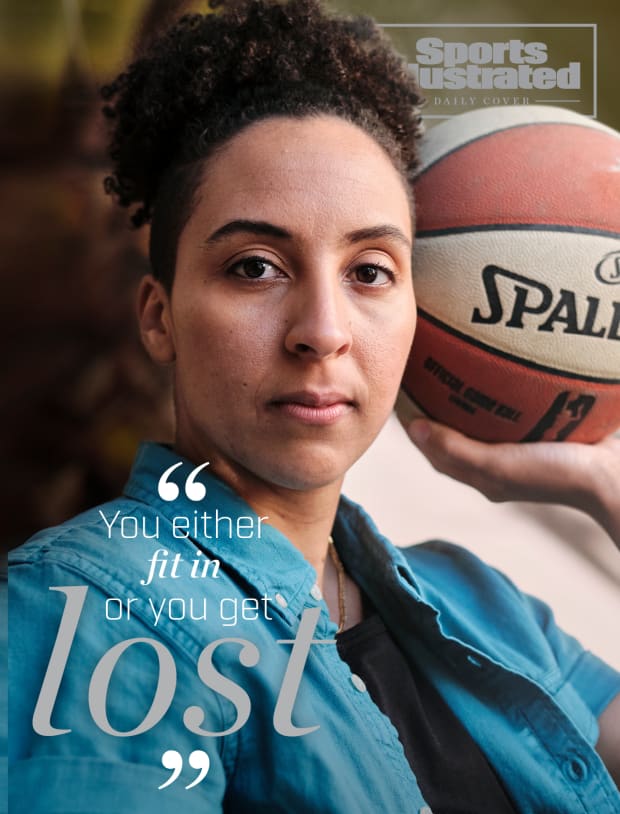

Trans athletes have become political lightning rods, but in a sex-segregated sports world, where do nonbinary people like Layshia Clarendon fit in?

It was in the WNBA bubble—the Wubble—that New York Liberty guard Layshia Clarendon made the decision. The Wubble was a stressful experience for Clarendon. For one, they were living through a pandemic. For another, life at the IMG Academy in Bradenton, Fla., was very small. Clarendon shuffled among their villa, the gym and games, like Groundhog Day designed for a professional athlete. They had also left their pregnant wife at home. (Clarendon alternately uses she, he and they pronouns.)

In her little time off, Clarendon became the face—and the force—behind the WNBA’s Say Her Name campaign, thinking about and talking about Black death on a near constant basis, busy with calls and webinars and brainstorming sessions. It was important work, and Clarendon felt called to do it, but it was draining, too. And there was another stressor that was draining Clarendon, one he wasn’t posting about on social media or sharing in postgame interviews: He couldn’t stop thinking about his chest.

Clarendon had no idea whether the WNBA would support their decision to have top surgery, a gender affirmation procedure that removes a person’s breasts and reshapes their chest to be flat, but they knew they would have the surgery regardless of how the league responded. The medical decision was not the struggle for Clarendon; the challenge was in figuring out whether she would be accepted by a sports world that was not designed for nonbinary trans people like her; she’d quietly updated the pronouns in her Twitter bio over the summer, but this was something different altogether. In the binary world of sports, leagues exist for men and for women. Clarendon sometimes feels like both of those things and other times feels like neither.

“It was something for me that was causing a lot of mental health issues,” Clarendon, 29, says of the worry about whether to move forward with top surgery and whether the WNBA would allow it—and what it would mean for his career if the league didn’t. “It made being in the bubble even harder than it [already] was.” It opened up a whole slate of questions that she had to consider, so after the season was over, she went to Terri Jackson, the executive director of the Women’s National Basketball Players Association (WNBPA). There was no precedent for this, but Jackson was all in to support Clarendon.

It’s generally considered bad form to focus on the particulars of trans people’s bodies, but as a professional athlete, the decisions Clarendon—or any trans athlete—makes about their body are incredibly consequential. Careers can hinge on them. The questions Clarendon considered included: What will the recovery look like and how will it impact my 2021 season? The league and my team have a right to know a lot about my body because it affects my play, but is there anything personal that the league can’t ask me about? I know I am going to publicly talk about my top surgery, but what if another player has top or bottom surgery and doesn’t want to share that with their team or the public? If the league doesn’t support me, can I be fired?

When I first spoke to Clarendon in December, a few weeks before their surgery, they were still trying to navigate these conversations with the WNBA. Luckily, they received the “full support” of commissioner Cathy Engelbert, as well as the Liberty and the WNBPA. On Jan. 29, the day that Clarendon announced her surgery on social media, coordinated statements went out from each of the league accounts, too.

It was a stark contrast to how the National Women’s Soccer League responded when Quinn, a midfielder for the OL Reign, came out as nonbinary and transgender on Instagram in September 2020.

“I wanted to make sure that my identity was represented in my workplace, and in the public sphere,” Quinn, 25, says now of the decision to post about their identity on social media. Their teammates and coach knew, but the public did not, which meant that Quinn had to deal with being misgendered in the press—having the wrong pronouns used—and feeling invisible on a daily basis. “I really wanted to be another visible person in the sports realm, especially playing at such a high level. I wanted to help others that were looking for people like themselves in sport.”

Quinn’s Instagram post made headlines. But while their announcement was met mostly with support from the public, the NWSL's official Twitter account took weeks to acknowledge the event, and the Reign’s account took even longer. When the NWSL finally did acknowledge it, it was a quote tweet of the BBC’s coverage of Quinn’s coming out. In Quinn’s first televised game after coming out, broadcasters got their pronouns wrong on-air.

The way the NWSL lacked explicit public support for Quinn after they came out was likely not ill-intentioned (the NWSL did not respond to multiple requests for comment). In the Reign’s case, the team did what it thought was most supportive of Quinn.

“Quinn privately shared their plans with the club prior to their public announcement. We believed this was Quinn’s information to disclose in whatever way they felt was right, and at whatever time they felt was appropriate,” Reign CEO Bill Predmore told Sports Illustrated via email. “While we were available to provide support if requested, the club was not involved in the form or timing of the announcement. Our view was that this was the most personal of news to share, so unless our support was specifically requested by Quinn, we should not impose our perspective to help shape the message nor should our club serve as the messenger.”

But it is an example of how unprepared most sports leagues are to support nonbinary athletes. The WNBA supported Clarendon as well as it did only because Clarendon advocated for themself behind the scenes for months. Quinn and Clarendon, alongside triathlete Rach McBride, are likely the only openly nonbinary athletes competing professionally in North American sports. But the number of out nonbinary athletes is only going to increase.

Trans athletes have become political lightning rods and targets of institutionalized oppression; already this year Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi have passed laws that purport to, in the words of Tennessee Governor Bill Lee, “preserve women’s athletics and ensure fair competition.” The focus on physiology and biology and arguments about “protecting women” predominantly impact transfeminine athletes and take away the humanity from people who just want to play the sports they love. In the highly gendered world of sport, it’s binary trans people—trans women and trans men—who are most visibly fighting for their right to compete. But left out of that conversation altogether are nonbinary athletes, who do not identify with a binary gender.

“People’s education level on trans people in general is extremely low,” says Ashland Johnson, the president and founder of the Inclusion Playbook, an advocacy group working to bring about social change through sports. “When it comes to nonbinary people, it’s sometimes nonexistent.”

The existence of nonbinary people complicates a seemingly neat and tidy way of organizing athletics: men’s sports and women’s sports. Including nonbinary folks in the conversation requires a willingness to acknowledge that the way we currently categorize athletics is in need of an overhaul, and that leagues need to make accommodations for the nonbinary athletes who are already here.

The concept of nonbinary gender identity is not simply a third gender category. Rather, nonbinary identity sees gender as a spectrum: A person can exist anywhere in between the binary genders or shatter the binary altogether. “Nonbinary” can mean neither man nor woman. It can mean both man and woman. It can mean a million other things in between, each personal to the individual.

Nonbinary people can be assigned female at birth (AFAB) or assigned male at birth (AMAB). They can be intersex—a term used to describe someone who is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn't fit neatly into the boxes of “female” or “male” as the categories are typically defined. Nonbinary people can choose aspects of medical transition for themselves, like feminizing or masculinizing hormones or gender-affirmation surgeries, or they might not medically transition at all.

“I've always known I was more than just a girl or a woman, but I didn’t know what exactly I was,” says Clarendon. “And so, identifying as nonbinary and trans in terms of the larger umbrella is really important to me. That gives me a place to belong and gives me community.”

“Nonbinary” gives Clarendon a word to identify with, one that encapsulates the fact that they feel like they are “equally both,” sometimes more male, sometimes more female, but definitely much bigger than “woman.” “It’s really important to me for that to be seen and for me to be whole,” he says. “My gender is just too big to fit in either box.”

Sports gave Clarendon the freedom to be herself even before she had the words to articulate her gender. As a kid growing up in San Bernadino, Calif., he didn’t know what transgender or nonbinary was; all he knew was that he felt best when he was in his hoops clothes.

They didn’t necessarily talk about gender with their teammates, but they knew there were people like them in sports, who liked to dress in gender nonconforming ways like they did. “That feeling of belonging is invaluable as a young person,” Clarendon says. “I loved the competitiveness of sports, chasing a goal, the camaraderie of being around teammates and how when I made a pass to someone and they scored it felt like we could accomplish anything.”

Clarendon says that realizing that gender could be fluid and ever-evolving was life-changing. He first identified publicly as “non-cisgender” in an article for The Players’ Tribune in 2015. But it took longer for them to embrace the idea that they belonged under the trans umbrella, requiring them to unpack some of their own internalized transphobia and seeing trans identity beyond the singular, dominant narrative of transitioning from one binary gender to the other. Last summer, during the WNBA season, she told teammates that she was changing her pronouns, and she quietly updated them in his Twitter bio.

McBride’s process was a gradual one, too. Growing up in Tacoma, Wash., and later, Germany, they dropped hints to loved ones for over a decade that they had what they call “gender struggles.” They first heard the term “genderqueer”—another term that describes someone whose gender lives outside the binary and can sometimes be used interchangeably with nonbinary—in their 20s and instinctively knew that was what they were, but didn’t hear much about that identity outside of classes at the University of Ottawa. They didn’t find another word to describe themselves, though, until about two years ago when they began exploring nonbinary identity and started talking publicly about it on social media before coming out in a 2020 story in Triathlete magazine. Last year, at 42, the Vancouver resident switched to exclusively using they/them pronouns.

McBride—known as the “Purple Tiger”—has been racing full-time as a triathlete since 2011 and was dubbed “the most interesting [person] in triathlon” by TRS Radio. They are a three-time Ironman 70.3 champion, have logged eight Ironman 70.3 fastest bike splits and are a two-time Ironman bike course record holder and a three-time course record holder—including the Canadian National Championships. But not being able to fully embody their true self during competitions made them feel like they weren’t reaching their full potential.

“Just recognizing my gender identity has created a space for me to feel more comfortable at the start line, because my experience before was of feeling odd and like I didn’t fit in and I didn’t understand why,” says McBride. “Now, I understand why and I can embrace that and I can still compete amongst the people I feel most comfortable with.”

As society’s understanding of gender shifts and more and more athletes come out as nonbinary, leagues need to be prepared to accept them—not just in words, but with concrete policies. Most professional sports leagues in the United States do not have trans-inclusion policies, though that is beginning to change. The National Women’s Hockey League, the first league to adopt one, created theirs out of necessity when Buffalo Beauts player Harrison Browne socially transitioned in 2016. The National Women’s Soccer League and Athletes Unlimited both unveiled theirs in March.

Interestingly, the leagues we currently think of as men’s leagues are actually more inclusive of trans and nonbinary athletes from a strictly rules-based perspective. MLB, the NHL, the NBA, the NFL and MLS do not have gender requirements for participants; anyone is eligible to play in those leagues. These leagues might need “to make sure [their] locker room culture is welcoming,” as one league employee put it, but they wouldn’t have to change any rules to allow trans or nonbinary athletes to play.

Therefore, it’s women’s leagues that will have to take a hard look at their existing policies. At the time these leagues were formed, trans and nonbinary athletes weren’t on their radar. But allowing anyone who is marginalized by gender to play in the women’s leagues stays true to their original goal: to provide opportunities for people who were being systematically shut out of professional sports.

It’s something that women’s leagues are beginning to think critically about. “Quinn’s announcement showed us that we have some work to do (both as a club and as a league) to reconcile a league that has been primarily defined by gender with the reality that the definition no longer reflects the full range of individuals who are playing in our league,” says Predmore. “I am optimistic that we’ll find a new and better way to define our league in a manner that doesn’t rely on gender, but instead is focused on the quality of the players, our values and the experience we provide to fans.”

For AFAB athletes who aren’t taking masculinizing hormones, women’s leagues currently allow them to stay—Quinn, Clarendon and McBride are examples of that. But even that can be thorny. For example, they have to deal with being misgendered every day just by nature of being in a women’s league. It also seemingly lumps them into the category of “woman-lite,” when they’re not.

There is no current equivalent out athlete for AMAB nonbinary people in men’s leagues. “Sport is not safe for trans people, and it’s certainly not safe for people in men’s sports who do not perform a certain type of masculinity,” says Chris Mosier, the first trans man to qualify for the U.S. duathlon team and the founder of TransAthlete.com. “There is a structure in sport that probably prevents AMAB nonbinary people from [openly] participating.”

As more leagues establish trans-inclusion policies, they are likely to look to existing policies for guidance. But experts say these policies are not as inclusive as they may first appear. To understand why, we must first talk about testosterone.

There is a long history of sex testing in sports, often under the guise of protecting cisgender women from men who might infiltrate their division and win, despite there being no evidence that has ever happened. Over the last century or so, sex testing has ranged from intrusive genital exams to chromosome testing to hormone testing focused on testosterone, which is currently considered the one true indicator of competitive advantage. This idea has come about regarding trans women’s desire to compete against other women, though research has shown that any “advantage” trans women may have gained through masculinizing puberty is not retained after one year of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with feminizing hormones like estrogen.

But testosterone is a hormone that occurs naturally at varying ranges, even in cisgender women. Despite the shaky (at best) science, the International Olympic Committee currently ascribes to a testosterone-based policy, as do the NCAA and many other elite sports governing bodies. These policies require that athletes competing in the women’s category have testosterone levels under a certain number. This can disproportionately subject Black and brown women, whose femininity is policed due to racist stereotyping, to challenges to “prove” their gender.

“There is no solid evidence for the 10 nanomoles per liter for this regulation,” says Katrina Karkazis, coauthor of the book Testosterone: An Unauthorized Biography. “It is an arbitrary threshold the IOC chose but cannot be explicitly tied to evidence of a performance difference based on T levels.”

The NWHL, NWSL and AU’s policies also center on testosterone. This is often missed in these conversations—how testosterone is being used to exclude not only transfeminine people, but transmasculine people, as well. AFAB players are able to stay in the NWHL and AU as long as they are not taking masculinizing hormones—testosterone—as part of their medical transition. (The NCAA has a similar policy.) It might be called a “trans-inclusion” policy, but “it’s inclusive in name only” says Karkazis. Testosterone, she explains, is “being instrumentalized towards a particular end. And that end is around exclusion.”

Harrison Browne’s experience makes that clear—he left the NWHL so he could start hormones. “Do I wish that I could still play, if I could play in the league right now?” Browne doesn’t hesitate. “Probably, yeah. I’m still healthy.”

And while Browne is a trans man and it could be argued that there were other reasons why a women’s league was not an acceptable place for him, what happens if the next AFAB player who wants to take testosterone to more fully embody their true gender is nonbinary and wants to remain in a women’s league?

“These are really important questions that I don’t think enough people are asking in enough different levels and positions,” says Clarendon. “Right now, you either fit in or you get lost. Like, you meet the NCAA or IOC standards that make you eligible to play on the men’s or women’s side, or you don’t. Or you transition and you get lost, forced to move on with your life and mourn the career you had playing the sport you were assigned at birth. What would be your hope?”

The NWSL policy differs from the other two in that it allows for a therapeutic use exemption (TUE) for AFAB players who are taking testosterone but whose levels remain “within the typical limits of women athletes,” which mimics the IOC standards. However, it does not explicitly allow for nonbinary players, despite having one currently playing in the league. (The NWSL did not return requests for comment about which advocacy groups it consulted regarding its policy.)

AU’s policy stands out from the others in that it does not specify a testosterone level for transfeminine athletes who want to compete on women’s teams, just that they must be taking testosterone-suppressing medication. This is a big win for trans women and AMAB nonbinary people looking to compete against women. It allows them to do so without policing what it means to be a woman, or forcing AMAB nonbinary people into the same standards women are held to, which could invalidate their gender identity. Mosier helped the AU draft its policy, and it’s a step forward.

However, like the NWSL and NWHL’s policies, AU’s shows how the IOC’s arbitrary guidelines are having a trickle-down effect that results in exclusion. “Our drug policy follows the IOC list of banned substances, which includes testosterone as a performing-enhancing drug,” a spokesperson for AU told Sports Illustrated. “Additionally, because our policy on transgender and nonbinary athletes is not based on testosterone levels, it would be very difficult to implement a policy that allows testosterone use.”

Not every AFAB nonbinary person will want to take testosterone. But some will. And it’s not just trans and nonbinary athletes impacted by these policies. Not only are T levels incredibly variable person-to-person and day-to-day, “there’s actually contrary evidence, meaning that sometimes it’s the people with the lower level who perform better,” says Karkazis. In other words, measuring someone’s testosterone levels alone won’t actually tell you anything about what their sports performance will look like. As they stand now, these policies will have the impact of potentially pushing out the very athletes the leagues currently claim to support, and that should be concerning to everyone.

Conversations about how sports should be organized are not new. There’s this idea that “the possibilities for the future are to maintain the fully sex-segregated system or to abolish it entirely,” says Elizabeth Sharrow, associate professor of public policy and history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and whose work focuses on equity, policy and Title IX. “But that is a false narrative.” A false binary, like gender itself. “We have the ability to imagine participatory or competitive structures in lots of different ways,” they explain. “But in order to do so we have to give up the notion that categorization for athletics is easy, or is most fair or justifiable when we base it on the question of sex.”

Proposed solutions involve classing sports more like wrestling—by weight class, or by height for a sport like basketball—than by gender (Nancy Leong explores some of these options in her 2017 paper “Against Women’s Sports”). These solutions are flawed, as well, but reimagining the way we think about sports in the first place will require blowing up everything we think we know about how they should look. Clarendon sees potential in widening the focus of women’s leagues to include all people marginalized by gender, in line with the original reason they were created, while Quinn imagines an inclusive space being one that explicitly celebrates the identities of everyone who plays. Until the entire concept of sex segregation is seen as no longer functioning, nonbinary athletes and those who advocate for them are forced to work within the existing systems to make them more inclusive of people they were not designed to include in the first place.

If leagues truly do want to make themselves places that allow athletes to be fully themselves, they need to create the space for them to do so. There are some changes that can be implemented tomorrow, like including a player’s pronouns on the team’s media guides, just like they do for name pronunciation or position. That simple act could have potentially avoided Quinn’s being misgendered on-air last fall, or McBride’s having the wrong pronouns used “almost 100 times” during a race broadcast, something that was incredibly demoralizing. “It’s just like little pinpricks, every single time I hear [the wrong pronoun],” McBride explains. “It’s like there’s just no effort given.”

Teams and leagues could also normalize social media and communications staffs asking players what pronouns they want used for them on their social platforms and whether they have a name they prefer to use other than their given name. Offering uniform or kit styles that better align with a player’s gender could be another option.

Browne says that when he came out, the NWHL’s press team was incredibly supportive, but he wishes they had created a list of questions that were off-limits for reporters. That would have saved Browne from being faced with intrusive questions about his body. And true inclusion may also require leagues to grapple with their names—potentially being willing to drop the word “women” to describe their athletes, since it’s not an accurate descriptor.

“The rigidity of sports goes against my identity, in that I find having an expansive gender very exciting,” says Quinn. “There’s ways that we are ‘supposed’ to perform gender, even in sports, like when it comes to our uniforms or the language that we use. And so those can be pretty restricting and can go against my identity.”

Those changes are likely to have a positive impact on the mental health of nonbinary athletes, something that would benefit their on-field performance, too. Surgeries are often considered necessary for something like an injury, because that impacts an athlete’s ability to perform. But for Clarendon, their top surgery was necessary, too, both for their emotional well-being off the court and their performance on it. Trying to compartmentalize their gender and their job was impossible.

“We’re [never talking about] how hard it was to have breasts and go to the pool in a swimsuit top and the dysphoria that you’re experiencing, and then how it affects your overall mental health,” says Clarendon. “I’m a big believer that the healthier athletes are, the healthier products and commodities they are. … Being a whole person makes you a better performer at the end of the day, which is what honestly coaches and owners are really worried about, because it’s the entertainment business.”

These strategies will also help the athletes who are not yet out, who haven’t even grappled with the question of their own gender identity because it feels impossible to do so when their job is on the line. “Segregated systems suppress even the possibility of self-exploration for a lot of athletes,” says Sharrow, “because it’s frightening to imagine losing something you love or that is actually your sources of income just because the structures that govern suggest your identity might be impossible.”

As it stands now, players who want to come out publicly are left to navigate the decision on their own. “I don’t believe Layshia is the only one; she is just the only one who is open about it,” says Terri Jackson, the executive director of the WNBPA. Without a formal support process, leagues are not equipped to have conversations with the press or address players’ identities on social media channels. This lack of institutional support and precedent likely prevents other players from coming out.

“There’s been so much talk about exclusion,” says Quinn. But those conversations distract from what they see as the real issue, which is getting back to the reason people—including, and maybe especially, nonbinary people—play sports: “because we love connecting with our bodies.”

One of the best parts for Quinn of being out publicly has been the new extended trans community that they’ve found as a result of sharing their truth openly. They began navigating their public identity largely on their own, though their Canadian national team has begun to have conversations about what a trans-inclusion policy could look like and the Reign has begun to be more publicly intentionally supportive. In February 2021, the team’s social media accounts posted a graphic advertising season tickets with an image of Quinn next to the text “They play here” and adding pronouns for every player and coach to their website. That, combined with the WNBA’s coordinated effort, is evidence of a shift. Life Time, a health and fitness company that runs athletic events, has implemented a third gender option, “nonbinary/genderqueer” for all in-person run and triathlon events for the remainder of 2021 and plans to offer it for their entire portfolio of events—both in-person and virtual—in 2022 and beyond.

But until sports as a whole are ready to have conversations about the ways in which they’re organized, relatively simple changes would allow players to fully embody their own identities and remain in the leagues they feel most comfortable. While Quinn and McBride say there are ways in which being in a women’s league sometimes rubs up uncomfortably against their gender, players like Clarendon, who says they “feel like both genders,” are perfectly at home in a women’s league, but are waiting for the league to catch up to them.

“I felt particularly proud [last] summer that it was a queer, nonbinary, Black person who was leading the social justice movement,” she says of her role on the W’s Social Justice Council. She just wishes the league would be ready to name that identity and own the totality of the identities under its umbrella. Because it’s not just a league of 144 women; Clarendon’s presence proves that. As vice president of the WNBPA and as one of the the oldest players on the Liberty’s young roster, he gets to be a voice for change and an example for the league’s next generation, one that is perhaps ready to talk openly about gender and identity among its players.

Clarendon is also entering the 2021 season with the freedom of being completely, fully, openly himself. They will no longer have the stress of wondering whether their league will accept them, whether they will have to fight for inclusion in a sport they have dedicated their life to. Even still, she knows these conversations are just beginning.

“There are only going to be more people who come out. We’ve been here the whole time,” Clarendon says. “My story is not that unique in that gender is an evolution. What is going to happen when Ryan Ruocco uses ‘he’ for me on a[n ESPN] broadcast? What if I go exclusively by ‘he’ tomorrow? Is the league ready for that?”

Britni de la Cretaz is a freelance writer whose work focuses on the intersections of sports, gender and culture. Their book, Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women's Football League, is forthcoming from Bold Type Books.

• The Faults in Our Tiny, Little Sports Stars

• The Unrivaled Arrival of Trevor Lawrence

• The Trade That Might Have Saved Caris LeVert

0 Comments