Bruce Trampler has been collecting sports memorabilia for ages, amassing an impressive bounty. But the legendary boxing matchmaker isn't interested in selling.

“Rick might’ve told you this story,” The Collector says as he draws out a long sigh.

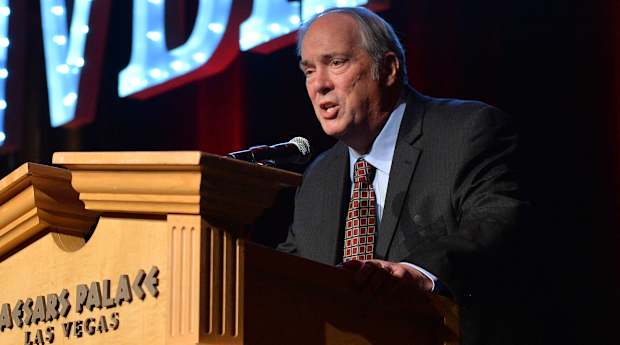

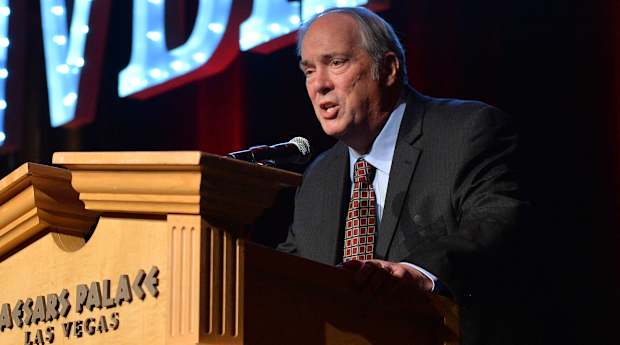

The Collector is Bruce Trampler. He’s calling from Las Vegas, home to the headquarters of his employer, Top Rank Boxing, and the most unexpected discovery in recent sports memorabilia history that anyone can recall. He’s dialing from his personal office, where this discovery—a bounty worth seven figures, if not eight—took place. But, to be clear, he’s neither selling, nor interested in doing so.

“Rick” would be Rick Mirigian, the boxing manager who steered Jose Ramirez to two titles at junior welterweight, who transformed Fresno into a fistic destination and who, apparently, is an amateur drawer rummager in his spare time. “I’m sitting at my desk, just like I am right now,” The Collector says, “and here’s this nosey, snoopy guy, and he pulls open the drawers without even asking.”

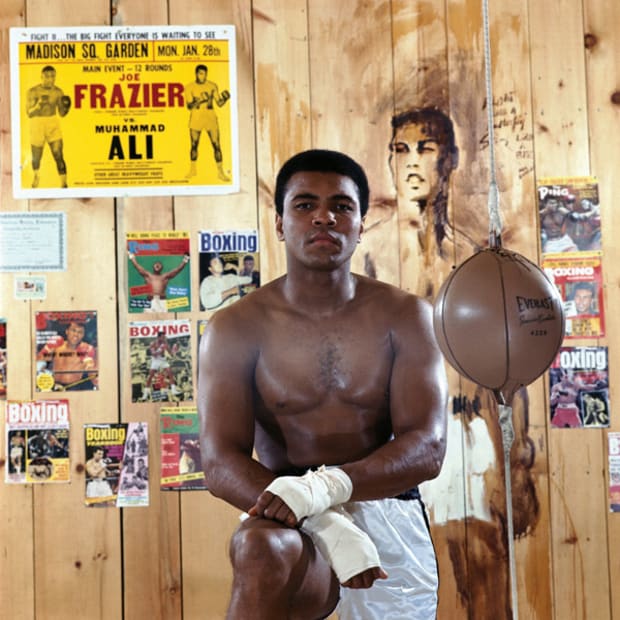

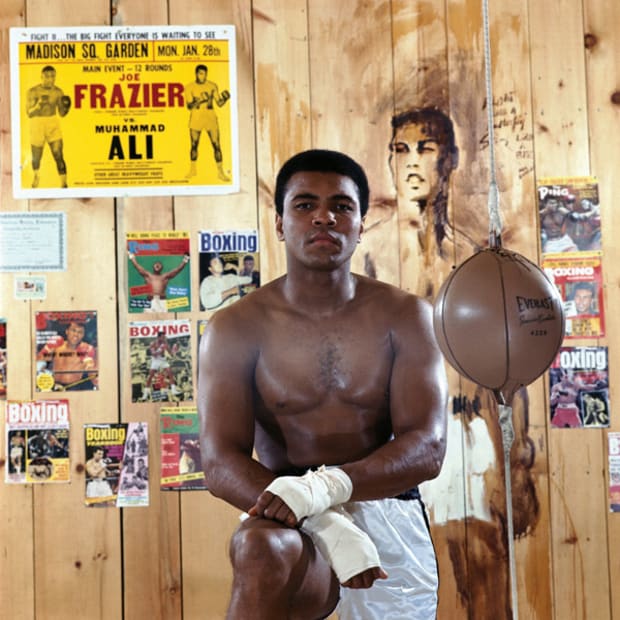

Guilty, Mirigian admits. He couldn’t believe the treasure Trampler had buried under piles of paperwork, everything gathering dust, shoved into corners, little organized or sorted. Mirigian found a poster from Ali-Frazier I, ticket stubs from bouts held 50 years ago, signed gloves, even 1979–80 Wayne Gretzky rookie cards that, if graded perfectly, could fetch over $1 million alone. Plus: hundreds of other precious cards, the exact value tough to determine before they’re graded. Mantle. Aaron. Roger Maris. Eddie Mathews. Canseco. Chamberlain. Max Schmeling. Trampler possessed multiples of many of them. Some were autographed, like the Schmeling one in which the boxer scratched out the swastika that had been stamped near his image. And there was more, quite a bit more, inside his garage and a nearby storage unit.

The first discovery happened six years ago, and as Ramirez became a star in the Top Rank stable, Mirigian made sure that on every contractual visit he built in time to snoop. “Stuff all over,” The Rummager says. “Piles of s--- literally two feet high. I like to say that Jimmy Hoffa is buried in there somewhere.”

The undefeated Ramirez (26–0) will headline a Top Rank card this Saturday, his latest bout a

highly anticipated unification fight against unbeaten Josh Taylor (17–0). Besides the four belts at stake in Las Vegas, this will give Mirigian another excuse to visit The Collector. They tend to settle into the same dance, these two, with Mirigian throwing out prices, estimating that Trampler’s collection could be worth from $3 million to $10 million and maybe even more. Mirigian believes it could be the “largest, modern-day, vintage-card collection”—meaning anywhere, for anyone. “Whatever Bob [Arum] paid you last year,” he told Trampler, referring to the founder of Top Rank, “I can tell you, you don’t need it anymore.”

Trampler will wave dismissively at such notions, because his collection isn’t about cash. Sometimes, he says, “It never crossed my mind” to sell it. Other times: “I just haven’t gotten around to throwing them out.”

Regardless, the dance speaks to how Trampler views his memorabilia. It’s not an investment to him, nor a portfolio, nor a way to buy a vacation home on an island somewhere. Instead, Trampler’s archive tells the story of a life in sports, his life, the one shaped by decades of experience and obsession. When Top Rank moved into its new offices a few years back, complete Topps baseball sets from 1952 and ’53 owned by Trampler disappeared between the company’s old home and its new one. The ’52 Mantle alone can sell for $1.5 million.

Sure, Trampler cared about the disappearance but not for the most obvious reason. Value, he argues, isn’t always money. Mirigian understands but pushed Trampler toward an estimate from an auction house, reasoning that he should at least have an idea of what the “junk” in those drawers was worth. “I’m a collector at heart,” Trampler responded. “I feel like I’m betraying some of these cards.”

The Collector, then, presents an antidote to the current card boom. “That purity just doesn’t exist anymore,” Mirigian says. “People collect now for money. He collected because it emotionally meant something to him.”

And: “The innocence of that makes him a walking piece of history himself.”

The Collector, now 71, grew up in New Jersey, where his parents would take him to watch minor league/independent baseball teams like the Newark Bears. Trampler devoured the sports sections of the morning and evening papers, focusing on baseball and boxing most intently and visiting the nearby library to study The Ring magazine. He’d also seek out the Sporting News, Sport magazine and Sports Illustrated, opening more windows into the life he wanted.

In Trampler’s teenage years, his father ferried him to Madame Bey’s boxing camp in Chatham Township, where champions like Rubin Carter, Floyd Patterson and Carlos Ortiz trained. To Trampler’s surprise, they welcomed him.

In college at Ohio, Trampler studied journalism. But he also hooked up with Don Elbaum, a prominent manager, promoter and matchmaker based in the Midwest. Through boxing and Elbaum’s connections, Trampler met athletes like Dean Chance, a Cy Young award winner. Teddy Brenner, Hall of Fame matchmaker, mentored him, along with Angelo Dundee, trainer to Muhammad Ali and others. “That’s how sports became my life,” Trampler says.

After graduation, Trampler went looking for a sports writing gig in 1971. He freelanced some for The Ring but started to branch out, using his boxing connections to represent or showcase fighters. Trampler has spent the half a century since immersed in a sport known for and defined by conflict, but it’s hard to find anyone who says a bad word about him.

Chance, the pitcher, decided to get into boxing, and he sent Trampler down to Orlando to run fight cards. Trampler put on 114 shows in 36 months. Brenner hooked him up with Mathews, who Trampler visited at a card show. When Matthews introduced him to Johnny Bench, Bo Belinsky and Joe Torre, it was, Trampler says, “like all my baseball cards came to life.” He realized then that he could merge his career in boxing with his passion for sports memorabilia, and when he encountered famous athletes, he asked for autographs.

The collection ballooned from there. Trampler’s life as a matchmaker took him all over the United States and to dozens of other countries, as he boosted the careers of legends like George Foreman, Floyd Mayweather Jr., Oscar De La Hoya, Erik Morales, Johnny Tapia and Miguel Cotto. He purchased more cards wherever he could find them and saved anything from promotions that called to his inner collector. He especially loved the traditional fight posters that Madison Square Garden officials created, the cardboard ones with yellow backgrounds and black-and-red type. He modeled his wedding invitation after that design and kept that, too. And each piece that Trampler held on to came to signify a memory, either from his childhood or his career.

Over time, the card and memorabilia industries changed, like everything else in sports. The costs ballooned. Investors moved in. Commercialization dominated. When Trampler visited one shop last month, he couldn’t help but notice the number of customers, how nicely they dressed and the cash figures thrown around. It’s not that The Collector views the new wave of memorabilia seekers with disdain. “That would be like being upset at somebody for buying stocks,” he says. But he saw the scene as indicative of a generation gap. He’ll never understand NFTs, or Non-Fungible Tokens. That’s not him.

The Collector never noticed just how much he had accumulated until he bumped into one Laura Smith in 1990. Now, on the day they met, Smith had already turned down the overtures from world champion boxer Alexis Arguello, when she decided to sit down with a “nice man” she had met earlier that day instead. She could hear the man’s friends making sounds like an airplane crashing in the background—a prediction, she would later learn, of how they expected that impromptu date would go. Still, they ordered two hot chocolates and went outside to the hotel pool. That day, Bruce told those friends he had found his future bride.

The Tramplers have been together ever since. Foreman served as their marriage officiant. Soon afterward, Laura asked if Bruce ever planned to get rid of all the cards, fight posters and boxing gloves that cluttered every square inch of their house. “That’s part of my childhood,” he told her, in way of saying that he planned to keep them. Over time, she gently pushed him to move everything into their garage, the storage space and, eventually, his office, so many valuable keepsakes crammed into so many cabinets. One day, Arum stumbled across the collection that looked like junk. “Bruce, can you bring some of this home?” he asked.

“No,” Trampler replied. “Laura won’t let me.”

Still, she came to understand how what her husband stubbornly held onto also, in large part, defined him. If everyone has a story, this is how Bruce told his. “He has this deep love for the games that people play,” she says.

And that was that, until The Rummager began to rifle. Mirigian offered to help and not for money. He wanted to show the same selfless nature that Trampler was known for in the boxing world to Trampler himself. He knew the matchmaker drove all over the country, looking for old fight records, advocating for boxers who didn’t have a voice. Laura welcomed this development, of course. “I hope Rick talks him into unloading some of it,” she says.

Mirigian offered to set Trampler up with Goldin Auctions. Trampler waffled. Johnny Krause, the auction manager at Goldin, says a compilation like the one The Collector uncovered by accident is rare, like finding a winning lottery ticket next to old boxing contracts and yellowing ticket stubs. The cash value, though, would depend entirely on the grades, meaning the variance could be wide and would be tinged by the massive industry uptick. In 2019, Goldin’s banked revenues around $30 million; in 2020, that number shot up to $110 million; this year, it already surpassed about $175 million—by May 6. “I’m dying to know all that’s in there,” Krause says.

“It’s not for sale,” Trampler insists. “I’m not getting rid of anything.”

More important; to him, anyway: The discovery led to more connections, to longtime colleagues who Trampler never knew loved amassing keepsakes as much as he did. People such as David McWater, a boxing lawyer/manager. Like Trampler, he buys cards and other memorabilia, often at auctions. Like Trampler, he would prefer not to know their true value, because “it takes some of the romance out of it.” And, like The Collector and The Rummager, The Lawyer sees gold inside that office—and not for any reasons that relate to the baseball card boom.

“That collection isn’t about the money,” McWater says. “It’s about how many people at your funeral say, Oh, my God. This guy was obsessed.”

More Boxing Coverage:

- Boxing Isn’t Dead. It’s Being Suffocated

- Old Fighters Coming Out of Retirement Won't Save Boxing

- Ryan Garcia Is On the Path to Becoming Boxing's Next Star

Bruce Trampler has been collecting sports memorabilia for ages, amassing an impressive bounty. But the legendary boxing matchmaker isn't interested in selling.

“Rick might’ve told you this story,” The Collector says as he draws out a long sigh.

The Collector is Bruce Trampler. He’s calling from Las Vegas, home to the headquarters of his employer, Top Rank Boxing, and the most unexpected discovery in recent sports memorabilia history that anyone can recall. He’s dialing from his personal office, where this discovery—a bounty worth seven figures, if not eight—took place. But, to be clear, he’s neither selling, nor interested in doing so.

“Rick” would be Rick Mirigian, the boxing manager who steered Jose Ramirez to two titles at junior welterweight, who transformed Fresno into a fistic destination and who, apparently, is an amateur drawer rummager in his spare time. “I’m sitting at my desk, just like I am right now,” The Collector says, “and here’s this nosey, snoopy guy, and he pulls open the drawers without even asking.”

Guilty, Mirigian admits. He couldn’t believe the treasure Trampler had buried under piles of paperwork, everything gathering dust, shoved into corners, little organized or sorted. Mirigian found a poster from Ali-Frazier I, ticket stubs from bouts held 50 years ago, signed gloves, even 1979–80 Wayne Gretzky rookie cards that, if graded perfectly, could fetch over $1 million alone. Plus: hundreds of other precious cards, the exact value tough to determine before they’re graded. Mantle. Aaron. Roger Maris. Eddie Mathews. Canseco. Chamberlain. Max Schmeling. Trampler possessed multiples of many of them. Some were autographed, like the Schmeling one in which the boxer scratched out the swastika that had been stamped near his image. And there was more, quite a bit more, inside his garage and a nearby storage unit.

The first discovery happened six years ago, and as Ramirez became a star in the Top Rank stable, Mirigian made sure that on every contractual visit he built in time to snoop. “Stuff all over,” The Rummager says. “Piles of s--- literally two feet high. I like to say that Jimmy Hoffa is buried in there somewhere.”

The undefeated Ramirez (26–0) will headline a Top Rank card this Saturday, his latest bout a highly anticipated unification fight against unbeaten Josh Taylor (17–0). Besides the four belts at stake in Las Vegas, this will give Mirigian another excuse to visit The Collector. They tend to settle into the same dance, these two, with Mirigian throwing out prices, estimating that Trampler’s collection could be worth from $3 million to $10 million and maybe even more. Mirigian believes it could be the “largest, modern-day, vintage-card collection”—meaning anywhere, for anyone. “Whatever Bob [Arum] paid you last year,” he told Trampler, referring to the founder of Top Rank, “I can tell you, you don’t need it anymore.”

Trampler will wave dismissively at such notions, because his collection isn’t about cash. Sometimes, he says, “It never crossed my mind” to sell it. Other times: “I just haven’t gotten around to throwing them out.”

Regardless, the dance speaks to how Trampler views his memorabilia. It’s not an investment to him, nor a portfolio, nor a way to buy a vacation home on an island somewhere. Instead, Trampler’s archive tells the story of a life in sports, his life, the one shaped by decades of experience and obsession. When Top Rank moved into its new offices a few years back, complete Topps baseball sets from 1952 and ’53 owned by Trampler disappeared between the company’s old home and its new one. The ’52 Mantle alone can sell for $1.5 million.

Sure, Trampler cared about the disappearance but not for the most obvious reason. Value, he argues, isn’t always money. Mirigian understands but pushed Trampler toward an estimate from an auction house, reasoning that he should at least have an idea of what the “junk” in those drawers was worth. “I’m a collector at heart,” Trampler responded. “I feel like I’m betraying some of these cards.”

The Collector, then, presents an antidote to the current card boom. “That purity just doesn’t exist anymore,” Mirigian says. “People collect now for money. He collected because it emotionally meant something to him.”

And: “The innocence of that makes him a walking piece of history himself.”

The Collector, now 71, grew up in New Jersey, where his parents would take him to watch minor league/independent baseball teams like the Newark Bears. Trampler devoured the sports sections of the morning and evening papers, focusing on baseball and boxing most intently and visiting the nearby library to study The Ring magazine. He’d also seek out the Sporting News, Sport magazine and Sports Illustrated, opening more windows into the life he wanted.

In Trampler’s teenage years, his father ferried him to Madame Bey’s boxing camp in Chatham Township, where champions like Rubin Carter, Floyd Patterson and Carlos Ortiz trained. To Trampler’s surprise, they welcomed him.

In college at Ohio, Trampler studied journalism. But he also hooked up with Don Elbaum, a prominent manager, promoter and matchmaker based in the Midwest. Through boxing and Elbaum’s connections, Trampler met athletes like Dean Chance, a Cy Young award winner. Teddy Brenner, Hall of Fame matchmaker, mentored him, along with Angelo Dundee, trainer to Muhammad Ali and others. “That’s how sports became my life,” Trampler says.

After graduation, Trampler went looking for a sports writing gig in 1971. He freelanced some for The Ring but started to branch out, using his boxing connections to represent or showcase fighters. Trampler has spent the half a century since immersed in a sport known for and defined by conflict, but it’s hard to find anyone who says a bad word about him.

Chance, the pitcher, decided to get into boxing, and he sent Trampler down to Orlando to run fight cards. Trampler put on 114 shows in 36 months. Brenner hooked him up with Mathews, who Trampler visited at a card show. When Matthews introduced him to Johnny Bench, Bo Belinsky and Joe Torre, it was, Trampler says, “like all my baseball cards came to life.” He realized then that he could merge his career in boxing with his passion for sports memorabilia, and when he encountered famous athletes, he asked for autographs.

The collection ballooned from there. Trampler’s life as a matchmaker took him all over the United States and to dozens of other countries, as he boosted the careers of legends like George Foreman, Floyd Mayweather Jr., Oscar De La Hoya, Erik Morales, Johnny Tapia and Miguel Cotto. He purchased more cards wherever he could find them and saved anything from promotions that called to his inner collector. He especially loved the traditional fight posters that Madison Square Garden officials created, the cardboard ones with yellow backgrounds and black-and-red type. He modeled his wedding invitation after that design and kept that, too. And each piece that Trampler held on to came to signify a memory, either from his childhood or his career.

Over time, the card and memorabilia industries changed, like everything else in sports. The costs ballooned. Investors moved in. Commercialization dominated. When Trampler visited one shop last month, he couldn’t help but notice the number of customers, how nicely they dressed and the cash figures thrown around. It’s not that The Collector views the new wave of memorabilia seekers with disdain. “That would be like being upset at somebody for buying stocks,” he says. But he saw the scene as indicative of a generation gap. He’ll never understand NFTs, or Non-Fungible Tokens. That’s not him.

The Collector never noticed just how much he had accumulated until he bumped into one Laura Smith in 1990. Now, on the day they met, Smith had already turned down the overtures from world champion boxer Alexis Arguello, when she decided to sit down with a “nice man” she had met earlier that day instead. She could hear the man’s friends making sounds like an airplane crashing in the background—a prediction, she would later learn, of how they expected that impromptu date would go. Still, they ordered two hot chocolates and went outside to the hotel pool. That day, Bruce told those friends he had found his future bride.

The Tramplers have been together ever since. Foreman served as their marriage officiant. Soon afterward, Laura asked if Bruce ever planned to get rid of all the cards, fight posters and boxing gloves that cluttered every square inch of their house. “That’s part of my childhood,” he told her, in way of saying that he planned to keep them. Over time, she gently pushed him to move everything into their garage, the storage space and, eventually, his office, so many valuable keepsakes crammed into so many cabinets. One day, Arum stumbled across the collection that looked like junk. “Bruce, can you bring some of this home?” he asked.

“No,” Trampler replied. “Laura won’t let me.”

Still, she came to understand how what her husband stubbornly held onto also, in large part, defined him. If everyone has a story, this is how Bruce told his. “He has this deep love for the games that people play,” she says.

And that was that, until The Rummager began to rifle. Mirigian offered to help and not for money. He wanted to show the same selfless nature that Trampler was known for in the boxing world to Trampler himself. He knew the matchmaker drove all over the country, looking for old fight records, advocating for boxers who didn’t have a voice. Laura welcomed this development, of course. “I hope Rick talks him into unloading some of it,” she says.

Mirigian offered to set Trampler up with Goldin Auctions. Trampler waffled. Johnny Krause, the auction manager at Goldin, says a compilation like the one The Collector uncovered by accident is rare, like finding a winning lottery ticket next to old boxing contracts and yellowing ticket stubs. The cash value, though, would depend entirely on the grades, meaning the variance could be wide and would be tinged by the massive industry uptick. In 2019, Goldin’s banked revenues around $30 million; in 2020, that number shot up to $110 million; this year, it already surpassed about $175 million—by May 6. “I’m dying to know all that’s in there,” Krause says.

“It’s not for sale,” Trampler insists. “I’m not getting rid of anything.”

More important; to him, anyway: The discovery led to more connections, to longtime colleagues who Trampler never knew loved amassing keepsakes as much as he did. People such as David McWater, a boxing lawyer/manager. Like Trampler, he buys cards and other memorabilia, often at auctions. Like Trampler, he would prefer not to know their true value, because “it takes some of the romance out of it.” And, like The Collector and The Rummager, The Lawyer sees gold inside that office—and not for any reasons that relate to the baseball card boom.

“That collection isn’t about the money,” McWater says. “It’s about how many people at your funeral say, Oh, my God. This guy was obsessed.”

More Boxing Coverage:

0 Comments