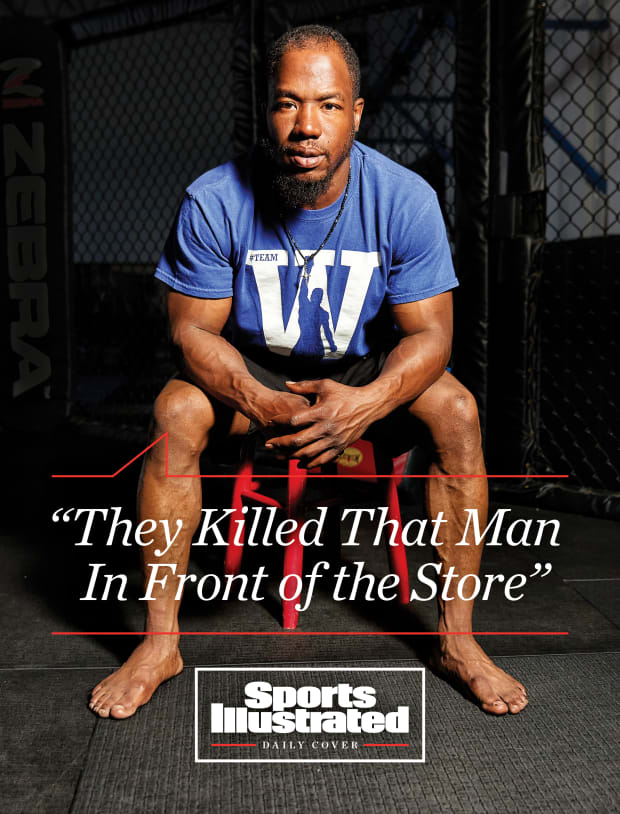

One year ago Donald Williams called 9-1-1 on Derek Chauvin and later he testified against the cop in court—but first he found courage in the violent cages of a combat sport.

Donald “the Deathwish” Williams had spent the last decade girding for battle. A professional mixed martial arts fighter based in Minneapolis, he brandished a professional record of 6–6. And he looked at this next assignation as if it were his 13th fight.

Williams, 33, would prepare for months, sometimes in front of a mirror, rehearsing and re-rehearsing his maneuvers. “To clear the head,” as he puts it, he spent nights shadowboxing. He vowed to give no quarter when pressed. In weaker moments, he would rely on the team around him for support. He thought about this upcoming confrontation as he went to sleep. It would consume his thoughts as soon as he woke.

The morning of the big day, he ate breakfast and dressed meticulously; he rolled his head as he gave himself a series of pep talks. He tried to find that constitutional sweet spot, aiming to stay calm but not be so casual that he would lack any edge or fall into traps. He wanted to be “hyped” (his word), but not so much that all the accumulated energy would cause him to deviate from the plan. He also needed to subdue the nerves that came with knowing that the crowds that watched his 12 previous MMA fights paled in comparison to the worldwide audience he now faced.

For this encounter in the early spring of 2021, Donald Williams II sparred not inside an MMA gym, but inside a Minneapolis courtroom. His opponent wasn’t another shirtless fighter but rather a defense lawyer, attired in a suit. Williams was less interested in a knockout than in satisfying a judge—and, more critically, 12 jurors tasked with deciding whether Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was responsible for the death of George Floyd.

Beginning March 30, Williams was no longer the Deathwish. Nobody cared about his weight, his height or his reach. He was there to testify.

Williams had stood on a curb last May 25—one year ago today—looking on in horror as Chauvin planted his left knee on Floyd’s neck until the life was drained out of him. Williams was also the guy who called 9-1-1 on Chauvin and three Minneapolis PD colleagues. As Williams would later put it, “I called the cops on the cops.”

When his name was called and he was summoned and it came time to testify, Williams was, yes, an eyewitness—but also a kind of expert witness. As an MMA fighter, he was intimately familiar with using leverage to immobilize. And with choke holds. He had applied them. He had experienced them applied to him. He knew how and when chokes were executed. Crucially, he knew how and when they ought to be released. And both his eyes and his experience led him to conclude that on May 25 he had witnessed a murder.

Donald Williams II came to MMA naturally and honestly. He had uncles who boxed professionally in Illinois, where his father long ago won the state championship as a wrestler. In his own high school days, Donald, too, was a standout on the mats in Minnesota. After a stint in junior college, he made the transition to mixed martial arts. Compactly built and quick on his feet, he never considered himself a fighter, just a natural athlete too short to play basketball and too slight to play football. The rhythms of MMA fed something in him.

“Being in the gym always kept me calm and humbled,” he says. “It taught me how to stand on my own two feet as a man. It gave me discipline. It separated me from my circle of friends because it gave me a different outlet.”

Mostly fighting at 135 lbs., Williams already had sprawling and wrestling skills; he was improving at kicking and striking. In the MMA hotbed that is the Twin Cities, though, he had location on his side, too. Under Greg Nelson, one of the sport’s pioneers and mentors, Williams trained at the Minnesota Martial Arts Academy, where it was no surprise to see UFC royalty walk through the door. He routinely sparred with Sean “the Muscle Shark” Sherk, a UFC lightweight champion. Other days, as he made his transition from wrestling to MMA, he would roll alongside “Thug” Rose Namajunas; her boyfriend and former UFC fighter, Pat Barry; and even Brock Lesnar.

As an amateur, in 2010, Williams reeled off six wins in six months, sometimes taking the fight with a methodical decision, other times with a violent knockout.

Turning pro, he began tracing the arc of so many other MMA fighters, striving to move up the org chart and get to the UFC.

As his 6–6 professional record attests: for every exhilarating win, there’s been a deflating loss. He’s been among the most popular draws in Minnesota, winning fights with electrifying violence that provided him with the determination to train full-time. And he’s experienced defeats that left him drained of both confidence and funds. In his most recent fight, in March 2019, he not only lost but tore his LCL.He’s had sponsors and managers come and go. He’s fought in promotions, mostly in Minnesota, that have run out of money. Like so many journeyman MMA fighters, he’s wrestled with time management, conflicted about whether to bet on himself and commit to fighting full-time or seek the financial stability of steady employment, which exacts a price on training. When he moonlighted as a security guard, he would wish that he was training. When he trained full-time, he worried about finances. Williams’s situation was—and is—compounded by his desire to provide for four kids, “two biological and two bonus,” as he explains it.

It is the bane of the individual-sport athlete. With no guaranteed contracts and no injured reserve list, when you’re sidelined the checks don’t come. In the spring of 2020—as if the pandemic wasn’t taking enough of a toll—Donald Williams II was learning this the hard way.

Rehabbing from his knee injury, Williams focused on the landscaping business he’d launched. But he got a late start on the morning of May 25 because he’d taken one of his sons fishing on Valentine Lake. The kid caught three bass; Donald caught nothing. Who cares? It had been the kind of thoroughly pleasant late-spring morning that can make Upper Midwest winters bearable.

But by early afternoon it was time to get to work. Before buckling down, Williams figured he’d go to Cup Foods, a corner grocery store in South Minneapolis, and pick up an energy drink. It was, at once, a reflexive decision and a life-changing decision.

Williams never made it into the store. “The surroundings stopped me,” he would later tell a jury. “The energy was off and I just couldn’t get in the door.”

On the corner of 38th St. and Chicago Ave. there was commotion. Williams saw a cluster of police and a pair of legs poking out alongside a vehicle. As he looked closer and conferred with other onlookers, he started to grasp what was happening. A handcuffed man was lying flat on his stomach, subdued by a policeman kneeling on the man’s neck while three other officers looked on.

Watching this unfold, Williams felt a familiar surge of stress hormones. But in this case, neither fight nor flight made for a viable option. He had no interest in retreating or leaving the scene—not while another human being was under duress. This wasn’t just wrong; it was inhuman. But he also was reluctant to have a physical confrontation. Williams had always been taught to respect police. Besides that, they were armed. And he wasn’t.

Clad in a blue Northside Boxing Club sweatshirt, a pair of shorts and flip-flops, he thought about all that could go wrong in a confrontation. With a partner and four kids at home, he had to think about them. “I had so much rage,” he recalls. “But I had to stay in my body. … I was lost.”

Though not so lost that he failed to recognize the racial dimensions. A Black man on the ground. A white tormentor above him. Now a crowd of Black onlookers, paralyzed, fearing the repercussions. Williams recalls that his mind raced back to the 19th century. “It was almost like in slavery,” he says. “You have Black people watching them kill the man in front of the whole village. It's, like, foggy and you can’t do nothing about it. We just had to sit there.”

For Williams, this was all made worse by his recognition of the hold that Chauvin was applying. Having been sprawled on an MMA mat as he and innumerable sparring partners practiced choking techniques, Williams says that immediately he feared for Floyd’s life. As someone who had worked security and trained alongside police, too, he knew standard procedure. As he saw it, Chauvin’s applying his left knee to Floyd’s neck, cutting off oxygen to the brain, was a considerable departure from standard procedure.

In a deep, low-rolling voice, edged with panic, Williams began calling out the policemen. He says he locked eyes with Chauvin, but the officer looked away. He heard Floyd cry for air, then for his mother. And then he watched Floyd’s eyes retreat into his head in the manner of an MMA fighter “put to sleep.” Finally, he watched Floyd go limp.

By the time Floyd, now unconscious, was carried away, Williams was shaken. Minneapolis police would characterize what happened as a “medical incident during police interaction,” but Williams sensed the situation was far more grave. He grabbed his phone and called for help:

9-1-1 Operator: 9-1-1, what’s the address of the emergency?

Williams: The officer 987 killed, uh, a citizen in front of a Chicago, uh, store. He just pretty much just died. That wasn’t resisting arrest, he had his knee on the dude’s neck the whole time. Officer 987, the man went and, uh, went stopped breathing. He wasn’t resisting arrest or nothing; he was already handcuffed and they pretty much just killed the dude. I don’t even know if he dead for sure, but he was not responsive when the ambulance just came and got him and the officer that was just out here left, the one that actually just murdered the kid in front of everybody on 36th—38th and, uh, Chicago.

9-1-1 Operator: O.K., would you like to speak with a sergeant?

Williams: Yeah! Like, that was bogus what he just did to this man. He was unresponsive—he wasn’t resisting arrest or any of it.

9-1-1 Automated Response: You have reached the city of Minneapolis to reach someone in our property crimes division.

Williams: Well, murder is (inaudible) … murder is foul. You, you gon’ kill yourself, I already know it. Two more years. You gon’ shoot yourself, murderers, bro. Y’all n----- is murderers, bro.

Officer: Minneapolis Third Precinct

9-1-1 Operator: Yeah, he wants to speak with a supervisor relating to 320’s calls.

Williams: They killed that man in front of the store!

Williams did no work that day; instead he returned home. A quick jaunt to get a Red Bull, an errand designed to take a few minutes, had turned into a two-hour ordeal. “I never really got a drink,” he says. “I just got trauma.” When his girlfriend and kids asked where he’d been, he told them about all that he’d seen. Maybe it wasn’t quite so severe, they suggested, hopefully. He recalls that he retreated to the basement to calm himself and take inventory of it all.

By the end of the day, word of George Floyd’s death had become a media story that, of course, soon led to a national reckoning. The whole thing picked up momentum with a kind of escape velocity. Within 24 hours of taking his son fishing, Williams’s image and voice rocketed around the world.

The friends who predicted to Williams that he would eventually be asked to testify at a trial were correct. He was contacted by lawyers for the Floyd family, as well as by the team assembled to prosecute what would become, regardless of verdict, a watershed case.

Williams says he was happy to share his impressions from that “horrible” day. But he was struggling, too, with his own emotions, and his role in the trial complicated his mental health spadework. Fearful of contaminating his testimony or giving the defense potential avenues of attack, Williams, a natural extrovert, was instructed by the prosecution team in the lead-up not to speak to the media or use social media.

He began working, meanwhile, with a therapist, to process his trauma. He tried to channel his energy into running his businesses. More than ever, he threw himself into fatherhood. Above all, he coped by thinking about his upcoming appearance at Chauvin’s murder trial as his next MMA fight. “I studied my notes and read everything,” he says. “I knew my opponent was trying to get into my head and under my skin, just like a face-off.”

While there was no training camp or weight cut, Williams says that in the days before his testimony he saw his therapist four times. “Like a strength-and-conditioning coach, she was conditioning my mind to be good.”

Finally, wearing an aqua-colored button-down and a court-issued lanyard around his neck, tears sometimes welling in his eyes, Williams sat in the witness box, as Chauvin’s lawyer, Eric Nelson, peppered him with questions. Nelson’s central argument carried the unmistakable whiff of racial trope: Williams was an angry Black man whose emotion undercut his perception of what he saw and planted fear in Chauvin that afternoon, distracting the officer from using the proper amount of force.

Nelson asked Williams to confirm that he’d called Chauvin “tough guy,” then later “bogus” and “bum,” 13 times.

“You heard the video,” Williams responded flatly.

Nelson asked Williams to confirm that he’d used profanity, calling Chauvin a “b----” and a “p----.” And that, after Floyd was carried away, Williams told another officer, Tou Thao, “You will shoot yourself in the head for [your complicity].”

Williams explained that he was not expressing a wish, only a prediction.

Nelson asked Williams: “Is it fair to say you grew angrier and angrier?”

“I grew professional and professional. I stayed in my body,” Williams replied. “You can’t paint me out to be angry.”

Just as he would watch video and self-assess after a fight, Williams breaks down his moment on the stand. Asked how he grades his performance, he pauses and sighs. “I give myself, like, a B-plus,” he concludes. “I might have talked a little too much. I felt like I stumbled a little bit. But I didn't break or fall, you know?”

Others were more charitable, widely praising him on social media. The jury was clearly moved as well. On April 20, Chauvin was found guilty on three charges: second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

After the verdict was announced, Williams says he felt a weird alloy of emotions. Relief. Lingering anger. Some joy, tempered by the reality that this trial had hinged on a man’s death. You don’t do backflips after a murder conviction.

Williams also knows that he’ll likely be called to testify again in the trials of the other three officers. Like a decision in the ring, this ruling wasn’t wholly satisfactory. But it beat the alternative.

Then there’s his own fighting career. It’s been a rough year for Williams. He’s hired a law firm and is considering seeking recompense for the mental anguish. At one point, a group of friends started a GoFundMe to aid in his financial recovery.

And while one wouldn’t know by looking at him, he’s lost his conditioning. “I’m in the worst shape I’ve ever been in my life,” he says. “Because you deal with trauma, you lose things that you love, and you just have to figure out how to get it back.”

Still, he considers himself an active fighter, and he looks forward to getting back in the gym to train—and then back in the cage to fight. One might wonder how a man subjected to the events of last May 25 would still have the stomach for a combat sport. But that’s not how Williams sees it. MMA is not violence or mayhem; it’s competition. He wants to get back to it. And, to borrow a phrase, he will try to stay in his body.

Whenever that next fight comes, he knows the range of outcomes is considerable. He could not only lose but get hurt again. He could win—he might even score a quick knockout. He might have to slog for 15 minutes and get a decision. And, yes, he might find himself on the ground choking his opponent.

But if getting back in the cage means a return to some semblance of normalcy, it will also be different. No longer will any given fight be a referendum on his character or his toughness. That’s already been laid bare. As he sees it, one undeniable bit of good has come from this year: People—not least his kids—have witnessed Donald Williams II at his core.

“The world,” he says, “has finally gotten to see who I am, know what I mean?”

More George Floyd Coverage:

• Behind the Timberwolves' Fight For Racial Justice

• Where the Confederates Fell, Arthur Ashe Still Stands

• 'We Weren’t Welcome When This Guy Was Around—So Now He’s Not Welcome When We’re Around'

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories here

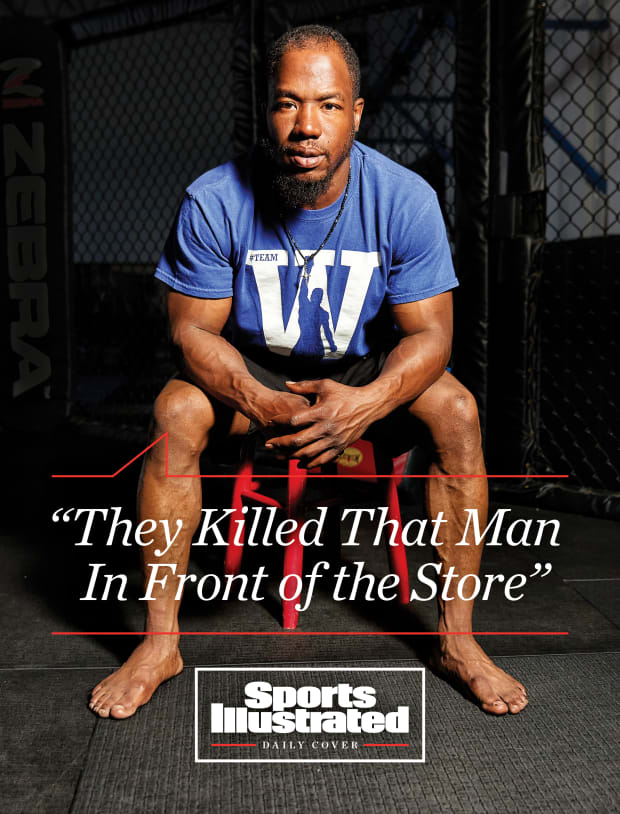

One year ago Donald Williams called 9-1-1 on Derek Chauvin and later he testified against the cop in court—but first he found courage in the violent cages of a combat sport.

Donald “the Deathwish” Williams had spent the last decade girding for battle. A professional mixed martial arts fighter based in Minneapolis, he brandished a professional record of 6–6. And he looked at this next assignation as if it were his 13th fight.

Williams, 33, would prepare for months, sometimes in front of a mirror, rehearsing and re-rehearsing his maneuvers. “To clear the head,” as he puts it, he spent nights shadowboxing. He vowed to give no quarter when pressed. In weaker moments, he would rely on the team around him for support. He thought about this upcoming confrontation as he went to sleep. It would consume his thoughts as soon as he woke.

The morning of the big day, he ate breakfast and dressed meticulously; he rolled his head as he gave himself a series of pep talks. He tried to find that constitutional sweet spot, aiming to stay calm but not be so casual that he would lack any edge or fall into traps. He wanted to be “hyped” (his word), but not so much that all the accumulated energy would cause him to deviate from the plan. He also needed to subdue the nerves that came with knowing that the crowds that watched his 12 previous MMA fights paled in comparison to the worldwide audience he now faced.

For this encounter in the early spring of 2021, Donald Williams II sparred not inside an MMA gym, but inside a Minneapolis courtroom. His opponent wasn’t another shirtless fighter but rather a defense lawyer, attired in a suit. Williams was less interested in a knockout than in satisfying a judge—and, more critically, 12 jurors tasked with deciding whether Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was responsible for the death of George Floyd.

Beginning March 30, Williams was no longer the Deathwish. Nobody cared about his weight, his height or his reach. He was there to testify.

Williams had stood on a curb last May 25—one year ago today—looking on in horror as Chauvin planted his left knee on Floyd’s neck until the life was drained out of him. Williams was also the guy who called 9-1-1 on Chauvin and three Minneapolis PD colleagues. As Williams would later put it, “I called the cops on the cops.”

When his name was called and he was summoned and it came time to testify, Williams was, yes, an eyewitness—but also a kind of expert witness. As an MMA fighter, he was intimately familiar with using leverage to immobilize. And with choke holds. He had applied them. He had experienced them applied to him. He knew how and when chokes were executed. Crucially, he knew how and when they ought to be released. And both his eyes and his experience led him to conclude that on May 25 he had witnessed a murder.

Donald Williams II came to MMA naturally and honestly. He had uncles who boxed professionally in Illinois, where his father long ago won the state championship as a wrestler. In his own high school days, Donald, too, was a standout on the mats in Minnesota. After a stint in junior college, he made the transition to mixed martial arts. Compactly built and quick on his feet, he never considered himself a fighter, just a natural athlete too short to play basketball and too slight to play football. The rhythms of MMA fed something in him.

“Being in the gym always kept me calm and humbled,” he says. “It taught me how to stand on my own two feet as a man. It gave me discipline. It separated me from my circle of friends because it gave me a different outlet.”

Mostly fighting at 135 lbs., Williams already had sprawling and wrestling skills; he was improving at kicking and striking. In the MMA hotbed that is the Twin Cities, though, he had location on his side, too. Under Greg Nelson, one of the sport’s pioneers and mentors, Williams trained at the Minnesota Martial Arts Academy, where it was no surprise to see UFC royalty walk through the door. He routinely sparred with Sean “the Muscle Shark” Sherk, a UFC lightweight champion. Other days, as he made his transition from wrestling to MMA, he would roll alongside “Thug” Rose Namajunas; her boyfriend and former UFC fighter, Pat Barry; and even Brock Lesnar.

As an amateur, in 2010, Williams reeled off six wins in six months, sometimes taking the fight with a methodical decision, other times with a violent knockout.

Turning pro, he began tracing the arc of so many other MMA fighters, striving to move up the org chart and get to the UFC. As his 6–6 professional record attests: for every exhilarating win, there’s been a deflating loss. He’s been among the most popular draws in Minnesota, winning fights with electrifying violence that provided him with the determination to train full-time. And he’s experienced defeats that left him drained of both confidence and funds. In his most recent fight, in March 2019, he not only lost but tore his LCL.

He’s had sponsors and managers come and go. He’s fought in promotions, mostly in Minnesota, that have run out of money. Like so many journeyman MMA fighters, he’s wrestled with time management, conflicted about whether to bet on himself and commit to fighting full-time or seek the financial stability of steady employment, which exacts a price on training. When he moonlighted as a security guard, he would wish that he was training. When he trained full-time, he worried about finances. Williams’s situation was—and is—compounded by his desire to provide for four kids, “two biological and two bonus,” as he explains it.

It is the bane of the individual-sport athlete. With no guaranteed contracts and no injured reserve list, when you’re sidelined the checks don’t come. In the spring of 2020—as if the pandemic wasn’t taking enough of a toll—Donald Williams II was learning this the hard way.

Rehabbing from his knee injury, Williams focused on the landscaping business he’d launched. But he got a late start on the morning of May 25 because he’d taken one of his sons fishing on Valentine Lake. The kid caught three bass; Donald caught nothing. Who cares? It had been the kind of thoroughly pleasant late-spring morning that can make Upper Midwest winters bearable.

But by early afternoon it was time to get to work. Before buckling down, Williams figured he’d go to Cup Foods, a corner grocery store in South Minneapolis, and pick up an energy drink. It was, at once, a reflexive decision and a life-changing decision.

Williams never made it into the store. “The surroundings stopped me,” he would later tell a jury. “The energy was off and I just couldn’t get in the door.”

On the corner of 38th St. and Chicago Ave. there was commotion. Williams saw a cluster of police and a pair of legs poking out alongside a vehicle. As he looked closer and conferred with other onlookers, he started to grasp what was happening. A handcuffed man was lying flat on his stomach, subdued by a policeman kneeling on the man’s neck while three other officers looked on.

Watching this unfold, Williams felt a familiar surge of stress hormones. But in this case, neither fight nor flight made for a viable option. He had no interest in retreating or leaving the scene—not while another human being was under duress. This wasn’t just wrong; it was inhuman. But he also was reluctant to have a physical confrontation. Williams had always been taught to respect police. Besides that, they were armed. And he wasn’t.

Clad in a blue Northside Boxing Club sweatshirt, a pair of shorts and flip-flops, he thought about all that could go wrong in a confrontation. With a partner and four kids at home, he had to think about them. “I had so much rage,” he recalls. “But I had to stay in my body. … I was lost.”

Though not so lost that he failed to recognize the racial dimensions. A Black man on the ground. A white tormentor above him. Now a crowd of Black onlookers, paralyzed, fearing the repercussions. Williams recalls that his mind raced back to the 19th century. “It was almost like in slavery,” he says. “You have Black people watching them kill the man in front of the whole village. It's, like, foggy and you can’t do nothing about it. We just had to sit there.”

For Williams, this was all made worse by his recognition of the hold that Chauvin was applying. Having been sprawled on an MMA mat as he and innumerable sparring partners practiced choking techniques, Williams says that immediately he feared for Floyd’s life. As someone who had worked security and trained alongside police, too, he knew standard procedure. As he saw it, Chauvin’s applying his left knee to Floyd’s neck, cutting off oxygen to the brain, was a considerable departure from standard procedure.

In a deep, low-rolling voice, edged with panic, Williams began calling out the policemen. He says he locked eyes with Chauvin, but the officer looked away. He heard Floyd cry for air, then for his mother. And then he watched Floyd’s eyes retreat into his head in the manner of an MMA fighter “put to sleep.” Finally, he watched Floyd go limp.

By the time Floyd, now unconscious, was carried away, Williams was shaken. Minneapolis police would characterize what happened as a “medical incident during police interaction,” but Williams sensed the situation was far more grave. He grabbed his phone and called for help:

9-1-1 Operator: 9-1-1, what’s the address of the emergency?

Williams: The officer 987 killed, uh, a citizen in front of a Chicago, uh, store. He just pretty much just died. That wasn’t resisting arrest, he had his knee on the dude’s neck the whole time. Officer 987, the man went and, uh, went stopped breathing. He wasn’t resisting arrest or nothing; he was already handcuffed and they pretty much just killed the dude. I don’t even know if he dead for sure, but he was not responsive when the ambulance just came and got him and the officer that was just out here left, the one that actually just murdered the kid in front of everybody on 36th—38th and, uh, Chicago.

9-1-1 Operator: O.K., would you like to speak with a sergeant?

Williams: Yeah! Like, that was bogus what he just did to this man. He was unresponsive—he wasn’t resisting arrest or any of it.

9-1-1 Automated Response: You have reached the city of Minneapolis to reach someone in our property crimes division.

Williams: Well, murder is (inaudible) … murder is foul. You, you gon’ kill yourself, I already know it. Two more years. You gon’ shoot yourself, murderers, bro. Y’all n----- is murderers, bro.

Officer: Minneapolis Third Precinct

9-1-1 Operator: Yeah, he wants to speak with a supervisor relating to 320’s calls.

Williams: They killed that man in front of the store!

Williams did no work that day; instead he returned home. A quick jaunt to get a Red Bull, an errand designed to take a few minutes, had turned into a two-hour ordeal. “I never really got a drink,” he says. “I just got trauma.” When his girlfriend and kids asked where he’d been, he told them about all that he’d seen. Maybe it wasn’t quite so severe, they suggested, hopefully. He recalls that he retreated to the basement to calm himself and take inventory of it all.

By the end of the day, word of George Floyd’s death had become a media story that, of course, soon led to a national reckoning. The whole thing picked up momentum with a kind of escape velocity. Within 24 hours of taking his son fishing, Williams’s image and voice rocketed around the world.

The friends who predicted to Williams that he would eventually be asked to testify at a trial were correct. He was contacted by lawyers for the Floyd family, as well as by the team assembled to prosecute what would become, regardless of verdict, a watershed case.

Williams says he was happy to share his impressions from that “horrible” day. But he was struggling, too, with his own emotions, and his role in the trial complicated his mental health spadework. Fearful of contaminating his testimony or giving the defense potential avenues of attack, Williams, a natural extrovert, was instructed by the prosecution team in the lead-up not to speak to the media or use social media.

He began working, meanwhile, with a therapist, to process his trauma. He tried to channel his energy into running his businesses. More than ever, he threw himself into fatherhood. Above all, he coped by thinking about his upcoming appearance at Chauvin’s murder trial as his next MMA fight. “I studied my notes and read everything,” he says. “I knew my opponent was trying to get into my head and under my skin, just like a face-off.”

While there was no training camp or weight cut, Williams says that in the days before his testimony he saw his therapist four times. “Like a strength-and-conditioning coach, she was conditioning my mind to be good.”

Finally, wearing an aqua-colored button-down and a court-issued lanyard around his neck, tears sometimes welling in his eyes, Williams sat in the witness box, as Chauvin’s lawyer, Eric Nelson, peppered him with questions. Nelson’s central argument carried the unmistakable whiff of racial trope: Williams was an angry Black man whose emotion undercut his perception of what he saw and planted fear in Chauvin that afternoon, distracting the officer from using the proper amount of force.

Nelson asked Williams to confirm that he’d called Chauvin “tough guy,” then later “bogus” and “bum,” 13 times.

“You heard the video,” Williams responded flatly.

Nelson asked Williams to confirm that he’d used profanity, calling Chauvin a “b----” and a “p----.” And that, after Floyd was carried away, Williams told another officer, Tou Thao, “You will shoot yourself in the head for [your complicity].”

Williams explained that he was not expressing a wish, only a prediction.

Nelson asked Williams: “Is it fair to say you grew angrier and angrier?”

“I grew professional and professional. I stayed in my body,” Williams replied. “You can’t paint me out to be angry.”

Just as he would watch video and self-assess after a fight, Williams breaks down his moment on the stand. Asked how he grades his performance, he pauses and sighs. “I give myself, like, a B-plus,” he concludes. “I might have talked a little too much. I felt like I stumbled a little bit. But I didn't break or fall, you know?”

Others were more charitable, widely praising him on social media. The jury was clearly moved as well. On April 20, Chauvin was found guilty on three charges: second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

After the verdict was announced, Williams says he felt a weird alloy of emotions. Relief. Lingering anger. Some joy, tempered by the reality that this trial had hinged on a man’s death. You don’t do backflips after a murder conviction.

Williams also knows that he’ll likely be called to testify again in the trials of the other three officers. Like a decision in the ring, this ruling wasn’t wholly satisfactory. But it beat the alternative.

Then there’s his own fighting career. It’s been a rough year for Williams. He’s hired a law firm and is considering seeking recompense for the mental anguish. At one point, a group of friends started a GoFundMe to aid in his financial recovery.

And while one wouldn’t know by looking at him, he’s lost his conditioning. “I’m in the worst shape I’ve ever been in my life,” he says. “Because you deal with trauma, you lose things that you love, and you just have to figure out how to get it back.”

Still, he considers himself an active fighter, and he looks forward to getting back in the gym to train—and then back in the cage to fight. One might wonder how a man subjected to the events of last May 25 would still have the stomach for a combat sport. But that’s not how Williams sees it. MMA is not violence or mayhem; it’s competition. He wants to get back to it. And, to borrow a phrase, he will try to stay in his body.

Whenever that next fight comes, he knows the range of outcomes is considerable. He could not only lose but get hurt again. He could win—he might even score a quick knockout. He might have to slog for 15 minutes and get a decision. And, yes, he might find himself on the ground choking his opponent.

But if getting back in the cage means a return to some semblance of normalcy, it will also be different. No longer will any given fight be a referendum on his character or his toughness. That’s already been laid bare. As he sees it, one undeniable bit of good has come from this year: People—not least his kids—have witnessed Donald Williams II at his core.

“The world,” he says, “has finally gotten to see who I am, know what I mean?”

More George Floyd Coverage:

• Behind the Timberwolves' Fight For Racial Justice

• Where the Confederates Fell, Arthur Ashe Still Stands

• 'We Weren’t Welcome When This Guy Was Around—So Now He’s Not Welcome When We’re Around'

0 Comments