Though the latest College Football Playoff model seems to have captured overwhelming support from the industry’s brass, it does carry a few issues.

The

12-team College Football Playoff model revealed Thursday is almost perfect, the athletic director said from the other side of the phone line.Almost, he reiterated.

Almost.

“The top four seeds don’t get to host a playoff game,” says the AD, who wished to remain anonymous. “I hope they can change their mind on that. It’s a key flaw.”

Nothing is perfect. And though the latest CFP proposal comes close, there are issues. Sports Illustrated spoke to more than a dozen college administrators to field reaction over a model that, by and large, seems to have captured overwhelming support from the industry’s brass.

FORDE: College Football Looks to be Getting Playoff Expansion Right

For starters, the model provides all 130 FBS teams an opportunity to make the field—different from any other version ever used in college football history. The proposal also guarantees a spot to at least one Group of 5 champion, and it places mandatory importance on winning a conference title, since the four byes are assigned only to the top four league champs.

Also, it still maintains a human element by using rankings from the selection committee and it features an aspect that has never existed in a major college football postseason: on-campus games.

Oh, but there are problems. Of course there are. There’s the aforementioned quandary regarding the site of the quarterfinals—at bowls instead of on campuses. While the top four seeds get a bye into the quarterfinals, they won’t host a game at their stadiums like seeds Nos. 5-8 in the first round.

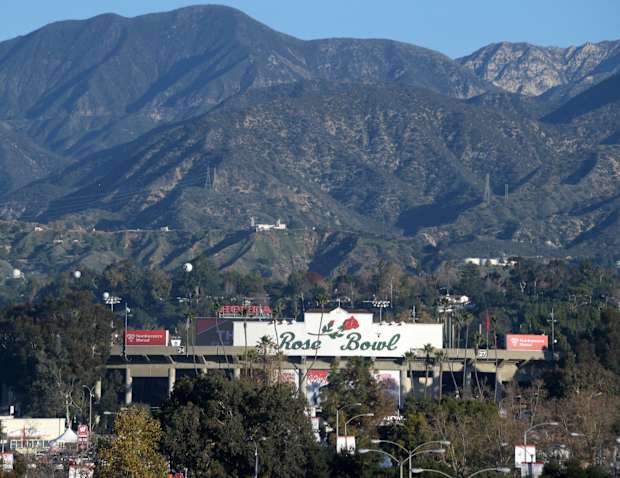

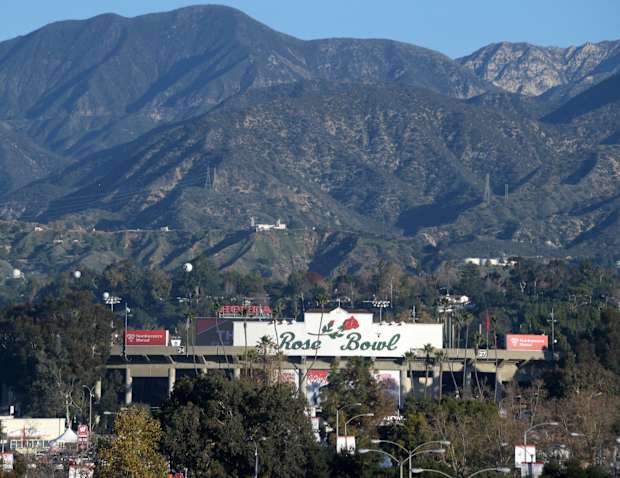

There’s also the issue of the Rose Bowl. Will it play ball?

And there’s the question of lengthening the season by another three games, potentially four for some teams. Also, first-round losers do not get the traditional bowl experience normally afforded to college football teams and, speaking of bowls, their future appears to even be at a more precarious position than it already was.

“There’s no perfect system,” says one administrator. “You can poke holes in any system all day long. People like poking holes.

“We could just go back to the old end-of-the season AP and UPI polls that worked for a century,” the administrator jests.

The holes are few and somewhat trivial in nature. In fact, one Group of 5 athletic director says it is impossible to put a hole through the big picture concept. Those within the industry heralded the CFP working group of Bob Bowlsby, Greg Sankey, Jack Swarbrick and Craig Thompson as chivalrous and diligent for a recommendation that incorporates the entirety of college football—not only the wealthy.

“For the first time in a long time, the best interests of the game were at the forefront rather than the provincial interests of the decision-makers,” says Tulane athletic director Troy Dannen.

Those who heard and saw the working group’s virtual presentation this week—led by Swarbrick—characterized it as incredibly thorough, thoughtful and somewhat airtight. The presentation even featured an intricate graphic showing how the last seven seasons would have played out using the proposed model.

MORE: What a 12-Team CFP Field Would've Looked Like in the Past

But for all the positivity and excitement around the model, there are issues. And the top one, at least with fans and some administrators, might be the site of the quarterfinals. While the four first-round games are on campus, a group of six bowls will host the four quarterfinals and two semifinals.

This issue drew the most attention from reporters—three different questions—during an hour-long teleconference Thursday with the CFP working group members. To their credit, they were surprisingly honest.

They did this to appease the bowls, which are big-money, historic partners in the sport. It gives the bowls "an opportunity to be relevant in the system," Thompson said.

"We've always honored the tradition of the bowl environment,” said Bowlsby.

However, the decision isn’t necessarily fan or school friendly. Fans of eight teams, instead of four, must travel. If a top-four seed advances to the title game, fans would have had to travel three times.

Schools, meanwhile, lose a marquee, money-making, on-campus playoff game. The model bucks a movement in college football to bring regular-season, neutral site games back on campus, celebrating what makes college football great: the pageantry of a campus and community environment.

But weather played a part in the decision, too, Bowlsby suggested.

"I don't think playing in East Lansing, Mich. on Jan. 7 is a good idea,” he said.

Maybe it’s not all about placating the bowls. One conference commissioner told SI that the neutral site is a way to remove home field advantage so deep into the playoffs.

“Alabama doesn’t want to play at Michigan in late December or vice-versa,” the commissioner says.

The quarterfinal sites are far from the most significant worry for some. The playoff’s biggest obstacle—“the sticking point,” a source says—is the Rose Bowl. The granddaddy of them all operates under a separate television contract, is historically entrenched in a specific date and time (New Year’s Day at 5 p.m. ET) and has, in the past, served as one of the more difficult negotiating partners.

In the 16-team proposal, the quarterfinals, while played on Jan. 1, would move to Jan. 2 if New Year’s Day falls on a Sunday. And what if the Rose hosts a semifinal? Those are expected to be played the following week.

“If they’re going to be part of the six bowl rotation,” says one high-placed source, “there are going to be times when you’re not playing on New Year’s Day at 5.”

The Rose Bowl’s longtime conference partners, the Big Ten and the Pac-12, are gearing up to protect its interest, says a Pac-12 source.

“For at least two conferences, the Rose Bowl will have to be a part of the discussion,” the administrator says.

And what about the length of the regular season? Teams that compete in their conference championship games and do not receive a bye could play as many as 17 games—an NFL regular season. Some are alarmed. Others shrug.

“It’s not that any of it is overwhelming, but it needs good vetting,” Clemson AD Dan Radakovich says.

Dannen has spent much of his career at the FCS level, where teams must play 16 games with 22 fewer scholarships.

“I’m not diminishing health and safety, but D2 and FCS play just as many games,” he says.

Some administrators suggest a lengthening of the regular season to correspond with the lengthening of the postseason. Does everyone begin the year on Week 0 and each team get an extra bye week? Or do you move up the entire calendar and play the league title games on Thanksgiving?

There are a lot of questions. And, for now, not so many answers.

“We need to be able to study the proposal and discuss it and populate college football with it and collect the data and feedback,” says ACC commissioner Jim Phillips.

While he agrees with much of the model, West Virginia athletic director Shane Lyons says there’s one thing he doesn’t like: the first-round losers won’t play in a bowl—unless they participate both in the playoff game and then a bowl game. That’s a longshot.

“I don’t think you can do that,” Lyons says. “If I’m a player and I get beat and you got to go to whatever bowl... I’m not sure how excited I am. I’m ready to go home.”

So, the playoff model proposes a lot of good and a little bad? That seems to be the consensus among high-level officials in the industry. For some, there’s a lot of good—a real lot, such as American Athletic Conference commissioner Mike Aresco, who purports his league as the sixth in what he calls the Power 6. The AAC champion would have qualified in five of the last seven years had the model been used then.

“This is the start of us finally getting rid of this G5 label,” he says. “It’s all FBS.”

One thing everyone can agree on: the model will almost certainly lead to a more exciting and tense final weeks of the season. Instead of six to eight teams in the hunt, more than 20 teams could be vying for a spot.

“I like the incentive of having to win late to get a bye or win late to get in,” says Florida AD Scott Stricklin.

“November is going to be crazy!” says another AD.

But where there is good, there is, of course, a sprinkle of bad. The proposal keeps more teams engaged deeper into the season, yes, but “at the top end it could negate excitement around the big Game of the Century types,” says one administrator. “Highly ranked teams remain in the playoff regardless of whether they win or lose those games.”

Alas, there is no perfect system. But college football executives will take this one—a lot of good and a little bad, they say.

More NCAA Football Coverage:

- ROSENBERG: Bo Schembechler Was a Flawed Man, Not Hero, of His Time

- The College Football Arrival of the 'Never-Punt' Coach

- FORDE: The Pac-12 Puts Its Future in Unexpected Hands

Though the latest College Football Playoff model seems to have captured overwhelming support from the industry’s brass, it does carry a few issues.

The 12-team College Football Playoff model revealed Thursday is almost perfect, the athletic director said from the other side of the phone line.

Almost, he reiterated.

Almost.

“The top four seeds don’t get to host a playoff game,” says the AD, who wished to remain anonymous. “I hope they can change their mind on that. It’s a key flaw.”

Nothing is perfect. And though the latest CFP proposal comes close, there are issues. Sports Illustrated spoke to more than a dozen college administrators to field reaction over a model that, by and large, seems to have captured overwhelming support from the industry’s brass.

FORDE: College Football Looks to be Getting Playoff Expansion Right

For starters, the model provides all 130 FBS teams an opportunity to make the field—different from any other version ever used in college football history. The proposal also guarantees a spot to at least one Group of 5 champion, and it places mandatory importance on winning a conference title, since the four byes are assigned only to the top four league champs.

Also, it still maintains a human element by using rankings from the selection committee and it features an aspect that has never existed in a major college football postseason: on-campus games.

Oh, but there are problems. Of course there are. There’s the aforementioned quandary regarding the site of the quarterfinals—at bowls instead of on campuses. While the top four seeds get a bye into the quarterfinals, they won’t host a game at their stadiums like seeds Nos. 5-8 in the first round.

There’s also the issue of the Rose Bowl. Will it play ball?

And there’s the question of lengthening the season by another three games, potentially four for some teams. Also, first-round losers do not get the traditional bowl experience normally afforded to college football teams and, speaking of bowls, their future appears to even be at a more precarious position than it already was.

“There’s no perfect system,” says one administrator. “You can poke holes in any system all day long. People like poking holes.

“We could just go back to the old end-of-the season AP and UPI polls that worked for a century,” the administrator jests.

The holes are few and somewhat trivial in nature. In fact, one Group of 5 athletic director says it is impossible to put a hole through the big picture concept. Those within the industry heralded the CFP working group of Bob Bowlsby, Greg Sankey, Jack Swarbrick and Craig Thompson as chivalrous and diligent for a recommendation that incorporates the entirety of college football—not only the wealthy.

“For the first time in a long time, the best interests of the game were at the forefront rather than the provincial interests of the decision-makers,” says Tulane athletic director Troy Dannen.

Those who heard and saw the working group’s virtual presentation this week—led by Swarbrick—characterized it as incredibly thorough, thoughtful and somewhat airtight. The presentation even featured an intricate graphic showing how the last seven seasons would have played out using the proposed model.

MORE: What a 12-Team CFP Field Would've Looked Like in the Past

But for all the positivity and excitement around the model, there are issues. And the top one, at least with fans and some administrators, might be the site of the quarterfinals. While the four first-round games are on campus, a group of six bowls will host the four quarterfinals and two semifinals.

This issue drew the most attention from reporters—three different questions—during an hour-long teleconference Thursday with the CFP working group members. To their credit, they were surprisingly honest.

They did this to appease the bowls, which are big-money, historic partners in the sport. It gives the bowls "an opportunity to be relevant in the system," Thompson said.

"We've always honored the tradition of the bowl environment,” said Bowlsby.

However, the decision isn’t necessarily fan or school friendly. Fans of eight teams, instead of four, must travel. If a top-four seed advances to the title game, fans would have had to travel three times.

Schools, meanwhile, lose a marquee, money-making, on-campus playoff game. The model bucks a movement in college football to bring regular-season, neutral site games back on campus, celebrating what makes college football great: the pageantry of a campus and community environment.

But weather played a part in the decision, too, Bowlsby suggested.

"I don't think playing in East Lansing, Mich. on Jan. 7 is a good idea,” he said.

Maybe it’s not all about placating the bowls. One conference commissioner told SI that the neutral site is a way to remove home field advantage so deep into the playoffs.

“Alabama doesn’t want to play at Michigan in late December or vice-versa,” the commissioner says.

The quarterfinal sites are far from the most significant worry for some. The playoff’s biggest obstacle—“the sticking point,” a source says—is the Rose Bowl. The granddaddy of them all operates under a separate television contract, is historically entrenched in a specific date and time (New Year’s Day at 5 p.m. ET) and has, in the past, served as one of the more difficult negotiating partners.

In the 16-team proposal, the quarterfinals, while played on Jan. 1, would move to Jan. 2 if New Year’s Day falls on a Sunday. And what if the Rose hosts a semifinal? Those are expected to be played the following week.

“If they’re going to be part of the six bowl rotation,” says one high-placed source, “there are going to be times when you’re not playing on New Year’s Day at 5.”

The Rose Bowl’s longtime conference partners, the Big Ten and the Pac-12, are gearing up to protect its interest, says a Pac-12 source.

“For at least two conferences, the Rose Bowl will have to be a part of the discussion,” the administrator says.

And what about the length of the regular season? Teams that compete in their conference championship games and do not receive a bye could play as many as 17 games—an NFL regular season. Some are alarmed. Others shrug.

“It’s not that any of it is overwhelming, but it needs good vetting,” Clemson AD Dan Radakovich says.

Dannen has spent much of his career at the FCS level, where teams must play 16 games with 22 fewer scholarships.

“I’m not diminishing health and safety, but D2 and FCS play just as many games,” he says.

Some administrators suggest a lengthening of the regular season to correspond with the lengthening of the postseason. Does everyone begin the year on Week 0 and each team get an extra bye week? Or do you move up the entire calendar and play the league title games on Thanksgiving?

There are a lot of questions. And, for now, not so many answers.

“We need to be able to study the proposal and discuss it and populate college football with it and collect the data and feedback,” says ACC commissioner Jim Phillips.

While he agrees with much of the model, West Virginia athletic director Shane Lyons says there’s one thing he doesn’t like: the first-round losers won’t play in a bowl—unless they participate both in the playoff game and then a bowl game. That’s a longshot.

“I don’t think you can do that,” Lyons says. “If I’m a player and I get beat and you got to go to whatever bowl... I’m not sure how excited I am. I’m ready to go home.”

So, the playoff model proposes a lot of good and a little bad? That seems to be the consensus among high-level officials in the industry. For some, there’s a lot of good—a real lot, such as American Athletic Conference commissioner Mike Aresco, who purports his league as the sixth in what he calls the Power 6. The AAC champion would have qualified in five of the last seven years had the model been used then.

“This is the start of us finally getting rid of this G5 label,” he says. “It’s all FBS.”

One thing everyone can agree on: the model will almost certainly lead to a more exciting and tense final weeks of the season. Instead of six to eight teams in the hunt, more than 20 teams could be vying for a spot.

“I like the incentive of having to win late to get a bye or win late to get in,” says Florida AD Scott Stricklin.

“November is going to be crazy!” says another AD.

But where there is good, there is, of course, a sprinkle of bad. The proposal keeps more teams engaged deeper into the season, yes, but “at the top end it could negate excitement around the big Game of the Century types,” says one administrator. “Highly ranked teams remain in the playoff regardless of whether they win or lose those games.”

Alas, there is no perfect system. But college football executives will take this one—a lot of good and a little bad, they say.

More NCAA Football Coverage:

0 Comments