He runs like a wideout and jumps like an NBA forward—and after his six-gold haul at the 2019 worlds, he's the heir to Michael Phelps

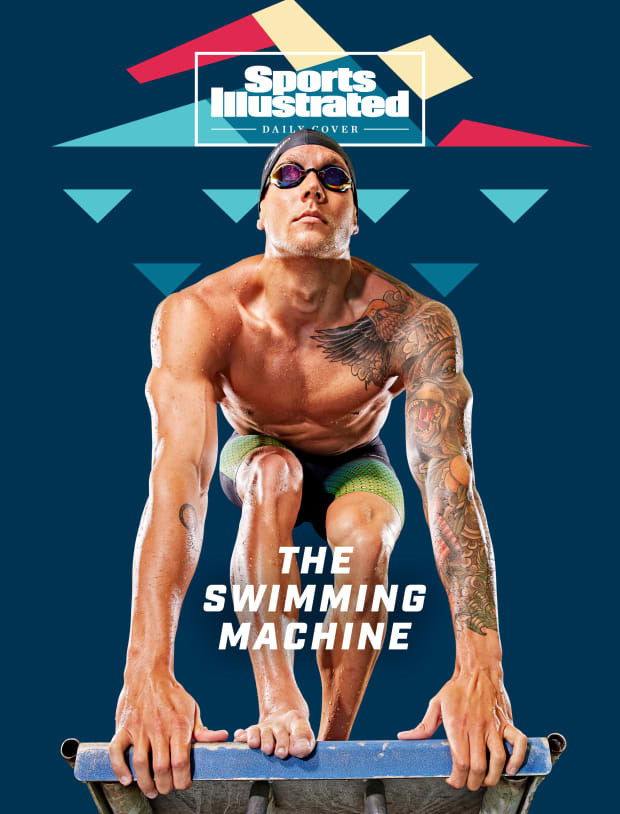

Jane Dressel is so excited that she cannot sit still. The favorite man in her life is 20 feet away, standing on a starting block and posing for pictures at the University of Florida’s indoor pool. He’s the embodiment of athletic excellence, strong and sleek, with an array of arresting visual elements: bronze skin covering rippling abs and obliques, a sleeve of tattoos on his left arm, liquid-blue eyes and perfectly white teeth.

The photo shoot goes on and on, and Jane is losing patience. When it finally ends, Caeleb Dressel walks Jane’s way—the moment she has been waiting for. Grabbing two white towels and tying them in a knot, he throws them into the pool. Tail wagging furiously, Jane the black Labrador retriever belly-flops into the water, briskly swimming to grab the towels in her mouth and return them to her owner.

Who let the dog in? The lifeguard on duty, acceding to Dressel’s unusual (and perhaps unsanitary) request for an impromptu dog paddle session after the shoot. Caeleb and his wife, Meghan, laugh and throw the towels out again—and Jane launches herself off a starting block. Then Dressel tosses in a swim cap. Then, what the heck, he throws himself into the pool to frolic with his pooch.

Just a man and his dog, swimming a couple of laps. It’s a snapshot of a blissfully simple life for the son of a veterinarian, the third of four kids raised on a rural plot of land in Green Cove Springs, Fla., 45 minutes south of Jacksonville. He grew up craving adventure and loving animals: Among many pets there was a ferret named Charlie, a pigeon named Terrence and a rat named Ellie (whose ashes are in an urn). Caeleb stayed in the area for college, bought land and married his high school sweetheart. “He’s got his wife, his farm and his dog,” says one USA Swimming staffer. “That’s all he needs.”

But the ripples from Dressel’s growing fame keep spreading as he tries to win as many as seven medals in Tokyo. The endorsements have piled up—Toyota, Coca-Cola, Speedo, Hershey’s—helping him buy a 10-acre spread south of Gainesville. From 2004 to ’16, either Michael Phelps or Ryan Lochte was considered the best male swimmer on the planet; now those legends are watching Dressel. The winner of two gold relay medals as a teenager in Rio, he is the next American Aquaman.

The 2019 world championships, in Gwangju, South Korea, where Dressel won six gold medals and two silvers, marked his coronation. In addition to breaking Phelps’s decade-old record in the 100-meter butterfly, he also swam the lowest freestyle times in history in the 50 (21.04) and the 100 (49.96), both in a textile suit; the only faster ones were recorded in ’09, when nontextile suit material was so buoyant it was subsequently banned.

The 24-year-old Dressel shares Phelps’s competitiveness and versatility but skews more toward sheer speed and power. He might not yet be the Usain Bolt of the pool, but he brings a similar jolt of electricity to the sprint events. Gracefully fluid beneath the water and startlingly forceful on top of it, with a Willy Wonka factory’s worth of eye candy as part of the package, Dressel may be the ultimate swimming spectacle.

Keenan Robinson is the director of sports medicine and science for USA Swimming. He worked closely with Phelps for more than a decade and now monitors biofeedback on every elite U.S. swimmer. I asked him what casual fans will think when they lay eyes on Dressel this summer.

His answer: “That is a swimmer?”

Dressel checks in at 6’ 2” and 198 pounds, with thicker slabs of muscle across the upper body than most of his peers. Matt DeLancey, Florida’s associate director of strength and conditioning for Olympic sports, puts Dressel on an athletic par with Grant Holloway, a former Gator and the current world-record holder in the 60-meter indoor hurdles. DeLancey recalls a workout in January 2020 that concluded with Dressel’s running six 20-meter sprints on the indoor turf in the Gators’ weight room beneath the south end zone stands of Florida Field. Steve Spurrier was watching while riding an exercise bike, and he called DeLancey over. Told who the sprinter was, the Head Ball Coach replied, “He should have played receiver for the Gators.”

Dressel has the measurables of an elite dry-land performer. His max lifts in cleans, snatches and squats are comparable to high-level football skill-position players. He claims not to know his vertical leap, but DeLancey says it is 43 inches, a height exceeded by only two players at the 2020 NBA combine. That seems legit if you’ve ever seen Dressel’s prerace jumps—a warning shot to rivals that they’re about to dive in against the most explosive man in swimming. “There’s never been anybody like him in the sport,” says Robinson, “just as a pure athlete.”

Dressel has a quick reaction time off the block, but his real separation comes in the 15 meters swimmers are allowed to be underwater before coming to the surface. That streamlined porpoise kicking is the fastest part of the race, and nobody in the world is better in that area than Dressel. “He is so efficient, so fish-like, so fast to 15 meters,” says Russell Mark, USA Swimming’s high performance manager. Where other swimmers rely on propelling themselves underwater with rapid down kicks, Dressel also generates considerable power kicking upward. Add that to a greater torsion with his shoulders and arms, and it creates an intriguing paradox: Dressel’s body undulates more slowly underwater than many of his competitors’, but he’s moving forward faster.

And then he hits the surface. “You have this beautiful, elegant movement underwater,” says Mark, “and then almost a violence above water.”

Dressel’s form once he reaches the surface actually isn’t as frenetic as it used to be. His stroke cycle rate (one rotation of each arm) has slowed but become more efficient as he’s gotten older and stronger—less sheer spinning, more powerful pulling of the water. Mark says Dressel’s cycle rate in the 50 free was between 0.85 seconds and 0.89 seconds as a freshman at Florida, almost a cartoon-fast tempo. While dominating at Gwangju in 2019, it was 0.99 seconds per cycle.

What sets Dressel apart from most sprinters is his ability to sustain his speed for the duration of a race. In the 100 free at worlds, Dressel was through the first 50 meters with a cycle rate of 1.18 seconds, then lowered it to 1.17 in the second 50—a finishing ability Mark calls “awesome.”

But beyond mechanics and athleticism there is the element all champions share: that sheer desire to reach the wall first. “He has a willingness to take any event on,” Robinson says. “Caeleb said, ‘I wish I could do the 1,500. I just don’t have the time.’ Whatever the environment is at that time and that situation, it’s optimal to him. He’s [like] a dog between the ears.” Robinson didn’t mean that in true canine terms, but Jane Dressel would consider that the highest compliment.

Mike Dressel climbs out of his Toyota Tundra pickup wearing his work scrubs and is followed out of the cab by his Labrador, Calpurnia. Named for a character in To Kill a Mockingbird, she goes to work with him at the veterinary clinic every day. As you may have surmised, the Dressels are never far from their dogs.

Mike got the idea to become a vet from reading All Creatures Great and Small while a freshman at Delaware. He moved to north Florida after finishing school, met Christina Cooper at a vet clinic and got married 31 years ago. They raised four kids who took to swimming, a sport neither parent knew much about.

That actually helped, Caeleb says, because they didn’t try to home-coach their children or obsess over the clock. “I don’t feel like less of a mom because I don’t know his times,” Christina says with a laugh. Mike reflexively shrinks away from backslaps for his son’s exploits. “It’s Caeleb doing it,” he says, “not me.”

The Dressels created a buffer between family time and pool time, with the former filled by one outdoor adventure after another—hunting, fishing, wakeboarding, anything that provides an adrenaline rush. Mike has a whiteboard that he calls his Dream Board, which includes hiking the entirety of the Appalachian Trail, one segment per year, with whichever kids are able to join him.

So last spring, when the pandemic shut down training, Caeleb joined the family in the mountains of Tennessee. He has jumped out of an airplane. In May, he went four-wheeling with his parents and got his pickup stuck in several feet of mud and water—Florida wildlife authorities had to tow them out. Many elite swimmers are homebodies on dry land, not wanting to risk injury or further fatigue during grueling periods of training; Dressel isn’t that way. “He does not put himself in a bubble,” Christina says. “It’s in our blood to always be doing something. He’ll call me and say, ‘Why am I out here digging up posts after practice while I’m exhausted?’ ”

Dressel has, in fact, always been an avid multitasker. He played a bunch of other sports growing up, most notably soccer (striker) and football (receiver). After transferring schools in sixth grade he didn’t even tell his new classmates that he swam. “I was embarrassed about it,” he says. “It wasn’t a cool sport, and I didn’t really love it that much.” It wasn’t until the verge of high school that he decided he liked swimming enough to focus on it.

Caeleb and his siblings—Tyler, Kaitlyn and Sherridon—eventually migrated from local club teams to The Bolles School, the prep powerhouse in Jacksonville. The Dressels still lived in Green Cove Springs and attended the local Clay High while training with the Bolles club team, making for some long days. Christina would wake up at 3:30 a.m., put together breakfast for her kids to eat in the car, then drive them 45 minutes to predawn workouts.

While setting national age-group records in high school and becoming the youngest male qualifier for the 2012 Olympic trials, Dressel showed how much he put into every race—and how much each one took out of him. At the junior national championships in Greensboro, N.C., in December ’13, he was on the verge of passing out after several races due to hyperventilation and bad air quality—often having to be led, gasping and wobbling, outside for fresh air. One night during the meet he was taken to the hospital to have his breathing checked.

Dressel had already signed with Florida, but after Greensboro he stepped away from the sport for several months. He sometimes drove to the pool for practice but wouldn’t go in. “I wasn’t in a good place mentally,” he says.

When Caeleb’s parents found out, they got him counseling and told Gators coach Gregg Troy that his star recruit might not be swimming in the fall. Troy and his staff went to visit Caeleb and told him the scholarship offer wasn’t going anywhere. “He was just flat-out worn out,” Troy says. “He got labeled as being one of the next great ones. He’s a bit of a pleaser, and he felt the need to be that all the time. There was an expectation of, What’s the next national record? It became too much pressure.”

Dressel reconnected with his love of the sport and reported to campus (whereupon he learned that his bow and arrow were not permitted in the dorms). Although some second-guessed the sprinter’s decision to swim at Florida for Troy—a coach known for his emphasis on distance races and high-yardage practices—it has been a record-breaking success. Troy pushed Caeleb, who sometimes pushed back. Ultimately the two found a common path. “He didn’t just live off the tools he has,” Troy says. “He’s worked to make the tools better. He can handle the work. You’ve just got to keep that gleam in his eye. He’s a better swimmer when he’s happy.”

Dressel won 10 NCAA titles and broke bundles of records, as the kid who used to carefully line up his crayons turned his perfectionist mindset into an analytical strength. He logged how he felt after every practice, lifting session and dry-land workout. He improved his diet during the pandemic and shut down almost all his social media. (He gives himself 15 minutes a day on Instagram.) “He’s a true student of the sport,” says former Olympian and former Gator Swim Club teammate Elizabeth Beisel. “He loves perfecting his craft.”

Having established himself as the fastest human ever in the short pool (25 meters), it was time to conquer the big pool (50 meters, the distance for all major international championships). Leading off the freestyle relay in Rio, his first Olympic swim was a nerve-racking highlight. “Caeleb’s an emotional person, and I know how nervous he was,” says Beisel, who was asked by Troy to personally walk Dressel to the ready room before the relay. “I don’t care what you talk about.” He told her, “Just get his mind off the race.”

It worked. Dressel finished his leg in 48.10 seconds, a virtual tie for first. Then Phelps dived in for the second leg and gave the U.S. the separation it needed for Ryan Held and Nathan Adrian to bring home the gold.

Dressel’s progression to becoming the top American male came just as Phelps and Lochte were stepping off the world stage (or perhaps being shoved off, in Lochte’s case). He was sensational at the 2017 world championships and then backed it up in ’19 under the pressure of rising expectations—an epic performance that took its toll.

The July air at Nambu University Aquatics Center in Gwangju was a miserable soup, thick and hot, and Mike Dressel quickly became a favorite in the U.S. cheering section by turning his handheld fan on the backs of spectators’ necks for a few seconds of relief. But after the final night of the competition, it was Caeleb who needed his assistance.

Christina, Mike and Meghan sneaked into the athlete entrance to the pool to meet Caeleb not long after he won the 4 × 100 freestyle relay, his eighth medal. They weren’t quite ready for what greeted them. He fell into their arms and actually took them to the ground in a tearful group hug. “He was visibly shaking and just collapsed,” Meghan recalls.

“I broke down,” Caeleb says. “I remember telling my dad that was the hardest thing mentally, physically that I’ve ever done. I started swimming at age 5, a whole life invested in leading up to this one moment. So, yeah, I broke down. I started crying. It was tough.”

Swimming eight events meant a nearly continuous cycle of warmups, warmdowns, massages, TV interviews, medal ceremonies, press conferences, trips through the media mixed zone, tightly timed meals and zealously guarded rest periods, all structured around pressurized competition. With his sprinter’s musculature, Dressel was constantly battling to lower his lactic acid during recovery to be ready for the next swim. By the time it was over, his body was beaten up and his mind was fried. His knuckles were raw and bloody from the constant struggle to pull on and strip off skintight racing suits, and his abs were spasming.

“It was nice to finally release that because you’ve got to kind of put on a façade the whole time that you’re competing,” Dressel says. “You don’t want to show anything, any behavior giveaways that your competition might see, right? You’ve got to pretty much brainwash yourself for a week. Everything’s O.K. Everything’s going to be O.K. And then once it’s done, you open the floodgates and crash into it.”

The toll from that meet is one of the reasons Dressel isn’t attempting to replicate Phelps’s epic eight-gold performance in Beijing from 2008. The GOAT set a standard not just for versatile excellence but also sustained focus that might be impossible for anyone to match. “He’s not Phelps,” Christina says. “He doesn’t want to be Phelps.”

As it is, Dressel will be incredibly busy in Tokyo. If all goes well, there will be three rounds of the 50 free, 100 free and 100 fly, plus at least three relays. Between July 26 and Aug. 1, he could be looking at 13 or more swims, with at least six likely to end in a trip to the medal podium. But he isn’t counting right now—at least not out loud. “Whatever other people expect me to do, whatever they’re comparing me to, I don’t care,” Dressel says. “I’m just trying to swim fast.”

At the end of this long and strange Olympics, Caeleb Dressel knows he can always come home to his wife, his family and his adoring black Lab. Jane doesn’t care how many medals her man wins; she just hopes he’ll take her out for a dog paddle again soon.

More Olympics Coverage:

• Welcome to Our Very Olympic Today Newsletter

• The Top Threats to the USWNT's Quest for Gold

• Q&A: Wrestler Helen Maroulis's Difficult Path Back to the Games

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories here

He runs like a wideout and jumps like an NBA forward—and after his six-gold haul at the 2019 worlds, he's the heir to Michael Phelps

Jane Dressel is so excited that she cannot sit still. The favorite man in her life is 20 feet away, standing on a starting block and posing for pictures at the University of Florida’s indoor pool. He’s the embodiment of athletic excellence, strong and sleek, with an array of arresting visual elements: bronze skin covering rippling abs and obliques, a sleeve of tattoos on his left arm, liquid-blue eyes and perfectly white teeth.

The photo shoot goes on and on, and Jane is losing patience. When it finally ends, Caeleb Dressel walks Jane’s way—the moment she has been waiting for. Grabbing two white towels and tying them in a knot, he throws them into the pool. Tail wagging furiously, Jane the black Labrador retriever belly-flops into the water, briskly swimming to grab the towels in her mouth and return them to her owner.

Who let the dog in? The lifeguard on duty, acceding to Dressel’s unusual (and perhaps unsanitary) request for an impromptu dog paddle session after the shoot. Caeleb and his wife, Meghan, laugh and throw the towels out again—and Jane launches herself off a starting block. Then Dressel tosses in a swim cap. Then, what the heck, he throws himself into the pool to frolic with his pooch.

Just a man and his dog, swimming a couple of laps. It’s a snapshot of a blissfully simple life for the son of a veterinarian, the third of four kids raised on a rural plot of land in Green Cove Springs, Fla., 45 minutes south of Jacksonville. He grew up craving adventure and loving animals: Among many pets there was a ferret named Charlie, a pigeon named Terrence and a rat named Ellie (whose ashes are in an urn). Caeleb stayed in the area for college, bought land and married his high school sweetheart. “He’s got his wife, his farm and his dog,” says one USA Swimming staffer. “That’s all he needs.”

But the ripples from Dressel’s growing fame keep spreading as he tries to win as many as seven medals in Tokyo. The endorsements have piled up—Toyota, Coca-Cola, Speedo, Hershey’s—helping him buy a 10-acre spread south of Gainesville. From 2004 to ’16, either Michael Phelps or Ryan Lochte was considered the best male swimmer on the planet; now those legends are watching Dressel. The winner of two gold relay medals as a teenager in Rio, he is the next American Aquaman.

The 2019 world championships, in Gwangju, South Korea, where Dressel won six gold medals and two silvers, marked his coronation. In addition to breaking Phelps’s decade-old record in the 100-meter butterfly, he also swam the lowest freestyle times in history in the 50 (21.04) and the 100 (49.96), both in a textile suit; the only faster ones were recorded in ’09, when nontextile suit material was so buoyant it was subsequently banned.

The 24-year-old Dressel shares Phelps’s competitiveness and versatility but skews more toward sheer speed and power. He might not yet be the Usain Bolt of the pool, but he brings a similar jolt of electricity to the sprint events. Gracefully fluid beneath the water and startlingly forceful on top of it, with a Willy Wonka factory’s worth of eye candy as part of the package, Dressel may be the ultimate swimming spectacle.

Keenan Robinson is the director of sports medicine and science for USA Swimming. He worked closely with Phelps for more than a decade and now monitors biofeedback on every elite U.S. swimmer. I asked him what casual fans will think when they lay eyes on Dressel this summer.

His answer: “That is a swimmer?”

Dressel checks in at 6’ 2” and 198 pounds, with thicker slabs of muscle across the upper body than most of his peers. Matt DeLancey, Florida’s associate director of strength and conditioning for Olympic sports, puts Dressel on an athletic par with Grant Holloway, a former Gator and the current world-record holder in the 60-meter indoor hurdles. DeLancey recalls a workout in January 2020 that concluded with Dressel’s running six 20-meter sprints on the indoor turf in the Gators’ weight room beneath the south end zone stands of Florida Field. Steve Spurrier was watching while riding an exercise bike, and he called DeLancey over. Told who the sprinter was, the Head Ball Coach replied, “He should have played receiver for the Gators.”

Dressel has the measurables of an elite dry-land performer. His max lifts in cleans, snatches and squats are comparable to high-level football skill-position players. He claims not to know his vertical leap, but DeLancey says it is 43 inches, a height exceeded by only two players at the 2020 NBA combine. That seems legit if you’ve ever seen Dressel’s prerace jumps—a warning shot to rivals that they’re about to dive in against the most explosive man in swimming. “There’s never been anybody like him in the sport,” says Robinson, “just as a pure athlete.”

Dressel has a quick reaction time off the block, but his real separation comes in the 15 meters swimmers are allowed to be underwater before coming to the surface. That streamlined porpoise kicking is the fastest part of the race, and nobody in the world is better in that area than Dressel. “He is so efficient, so fish-like, so fast to 15 meters,” says Russell Mark, USA Swimming’s high performance manager. Where other swimmers rely on propelling themselves underwater with rapid down kicks, Dressel also generates considerable power kicking upward. Add that to a greater torsion with his shoulders and arms, and it creates an intriguing paradox: Dressel’s body undulates more slowly underwater than many of his competitors’, but he’s moving forward faster.

And then he hits the surface. “You have this beautiful, elegant movement underwater,” says Mark, “and then almost a violence above water.”

Dressel’s form once he reaches the surface actually isn’t as frenetic as it used to be. His stroke cycle rate (one rotation of each arm) has slowed but become more efficient as he’s gotten older and stronger—less sheer spinning, more powerful pulling of the water. Mark says Dressel’s cycle rate in the 50 free was between 0.85 seconds and 0.89 seconds as a freshman at Florida, almost a cartoon-fast tempo. While dominating at Gwangju in 2019, it was 0.99 seconds per cycle.

What sets Dressel apart from most sprinters is his ability to sustain his speed for the duration of a race. In the 100 free at worlds, Dressel was through the first 50 meters with a cycle rate of 1.18 seconds, then lowered it to 1.17 in the second 50—a finishing ability Mark calls “awesome.”

But beyond mechanics and athleticism there is the element all champions share: that sheer desire to reach the wall first. “He has a willingness to take any event on,” Robinson says. “Caeleb said, ‘I wish I could do the 1,500. I just don’t have the time.’ Whatever the environment is at that time and that situation, it’s optimal to him. He’s [like] a dog between the ears.” Robinson didn’t mean that in true canine terms, but Jane Dressel would consider that the highest compliment.

Mike Dressel climbs out of his Toyota Tundra pickup wearing his work scrubs and is followed out of the cab by his Labrador, Calpurnia. Named for a character in To Kill a Mockingbird, she goes to work with him at the veterinary clinic every day. As you may have surmised, the Dressels are never far from their dogs.

Mike got the idea to become a vet from reading All Creatures Great and Small while a freshman at Delaware. He moved to north Florida after finishing school, met Christina Cooper at a vet clinic and got married 31 years ago. They raised four kids who took to swimming, a sport neither parent knew much about.

That actually helped, Caeleb says, because they didn’t try to home-coach their children or obsess over the clock. “I don’t feel like less of a mom because I don’t know his times,” Christina says with a laugh. Mike reflexively shrinks away from backslaps for his son’s exploits. “It’s Caeleb doing it,” he says, “not me.”

The Dressels created a buffer between family time and pool time, with the former filled by one outdoor adventure after another—hunting, fishing, wakeboarding, anything that provides an adrenaline rush. Mike has a whiteboard that he calls his Dream Board, which includes hiking the entirety of the Appalachian Trail, one segment per year, with whichever kids are able to join him.

So last spring, when the pandemic shut down training, Caeleb joined the family in the mountains of Tennessee. He has jumped out of an airplane. In May, he went four-wheeling with his parents and got his pickup stuck in several feet of mud and water—Florida wildlife authorities had to tow them out. Many elite swimmers are homebodies on dry land, not wanting to risk injury or further fatigue during grueling periods of training; Dressel isn’t that way. “He does not put himself in a bubble,” Christina says. “It’s in our blood to always be doing something. He’ll call me and say, ‘Why am I out here digging up posts after practice while I’m exhausted?’ ”

Dressel has, in fact, always been an avid multitasker. He played a bunch of other sports growing up, most notably soccer (striker) and football (receiver). After transferring schools in sixth grade he didn’t even tell his new classmates that he swam. “I was embarrassed about it,” he says. “It wasn’t a cool sport, and I didn’t really love it that much.” It wasn’t until the verge of high school that he decided he liked swimming enough to focus on it.

Caeleb and his siblings—Tyler, Kaitlyn and Sherridon—eventually migrated from local club teams to The Bolles School, the prep powerhouse in Jacksonville. The Dressels still lived in Green Cove Springs and attended the local Clay High while training with the Bolles club team, making for some long days. Christina would wake up at 3:30 a.m., put together breakfast for her kids to eat in the car, then drive them 45 minutes to predawn workouts.

While setting national age-group records in high school and becoming the youngest male qualifier for the 2012 Olympic trials, Dressel showed how much he put into every race—and how much each one took out of him. At the junior national championships in Greensboro, N.C., in December ’13, he was on the verge of passing out after several races due to hyperventilation and bad air quality—often having to be led, gasping and wobbling, outside for fresh air. One night during the meet he was taken to the hospital to have his breathing checked.

Dressel had already signed with Florida, but after Greensboro he stepped away from the sport for several months. He sometimes drove to the pool for practice but wouldn’t go in. “I wasn’t in a good place mentally,” he says.

When Caeleb’s parents found out, they got him counseling and told Gators coach Gregg Troy that his star recruit might not be swimming in the fall. Troy and his staff went to visit Caeleb and told him the scholarship offer wasn’t going anywhere. “He was just flat-out worn out,” Troy says. “He got labeled as being one of the next great ones. He’s a bit of a pleaser, and he felt the need to be that all the time. There was an expectation of, What’s the next national record? It became too much pressure.”

Dressel reconnected with his love of the sport and reported to campus (whereupon he learned that his bow and arrow were not permitted in the dorms). Although some second-guessed the sprinter’s decision to swim at Florida for Troy—a coach known for his emphasis on distance races and high-yardage practices—it has been a record-breaking success. Troy pushed Caeleb, who sometimes pushed back. Ultimately the two found a common path. “He didn’t just live off the tools he has,” Troy says. “He’s worked to make the tools better. He can handle the work. You’ve just got to keep that gleam in his eye. He’s a better swimmer when he’s happy.”

Dressel won 10 NCAA titles and broke bundles of records, as the kid who used to carefully line up his crayons turned his perfectionist mindset into an analytical strength. He logged how he felt after every practice, lifting session and dry-land workout. He improved his diet during the pandemic and shut down almost all his social media. (He gives himself 15 minutes a day on Instagram.) “He’s a true student of the sport,” says former Olympian and former Gator Swim Club teammate Elizabeth Beisel. “He loves perfecting his craft.”

Having established himself as the fastest human ever in the short pool (25 meters), it was time to conquer the big pool (50 meters, the distance for all major international championships). Leading off the freestyle relay in Rio, his first Olympic swim was a nerve-racking highlight. “Caeleb’s an emotional person, and I know how nervous he was,” says Beisel, who was asked by Troy to personally walk Dressel to the ready room before the relay. “I don’t care what you talk about.” He told her, “Just get his mind off the race.”

It worked. Dressel finished his leg in 48.10 seconds, a virtual tie for first. Then Phelps dived in for the second leg and gave the U.S. the separation it needed for Ryan Held and Nathan Adrian to bring home the gold.

Dressel’s progression to becoming the top American male came just as Phelps and Lochte were stepping off the world stage (or perhaps being shoved off, in Lochte’s case). He was sensational at the 2017 world championships and then backed it up in ’19 under the pressure of rising expectations—an epic performance that took its toll.

The July air at Nambu University Aquatics Center in Gwangju was a miserable soup, thick and hot, and Mike Dressel quickly became a favorite in the U.S. cheering section by turning his handheld fan on the backs of spectators’ necks for a few seconds of relief. But after the final night of the competition, it was Caeleb who needed his assistance.

Christina, Mike and Meghan sneaked into the athlete entrance to the pool to meet Caeleb not long after he won the 4 × 100 freestyle relay, his eighth medal. They weren’t quite ready for what greeted them. He fell into their arms and actually took them to the ground in a tearful group hug. “He was visibly shaking and just collapsed,” Meghan recalls.

“I broke down,” Caeleb says. “I remember telling my dad that was the hardest thing mentally, physically that I’ve ever done. I started swimming at age 5, a whole life invested in leading up to this one moment. So, yeah, I broke down. I started crying. It was tough.”

Swimming eight events meant a nearly continuous cycle of warmups, warmdowns, massages, TV interviews, medal ceremonies, press conferences, trips through the media mixed zone, tightly timed meals and zealously guarded rest periods, all structured around pressurized competition. With his sprinter’s musculature, Dressel was constantly battling to lower his lactic acid during recovery to be ready for the next swim. By the time it was over, his body was beaten up and his mind was fried. His knuckles were raw and bloody from the constant struggle to pull on and strip off skintight racing suits, and his abs were spasming.

“It was nice to finally release that because you’ve got to kind of put on a façade the whole time that you’re competing,” Dressel says. “You don’t want to show anything, any behavior giveaways that your competition might see, right? You’ve got to pretty much brainwash yourself for a week. Everything’s O.K. Everything’s going to be O.K. And then once it’s done, you open the floodgates and crash into it.”

The toll from that meet is one of the reasons Dressel isn’t attempting to replicate Phelps’s epic eight-gold performance in Beijing from 2008. The GOAT set a standard not just for versatile excellence but also sustained focus that might be impossible for anyone to match. “He’s not Phelps,” Christina says. “He doesn’t want to be Phelps.”

As it is, Dressel will be incredibly busy in Tokyo. If all goes well, there will be three rounds of the 50 free, 100 free and 100 fly, plus at least three relays. Between July 26 and Aug. 1, he could be looking at 13 or more swims, with at least six likely to end in a trip to the medal podium. But he isn’t counting right now—at least not out loud. “Whatever other people expect me to do, whatever they’re comparing me to, I don’t care,” Dressel says. “I’m just trying to swim fast.”

At the end of this long and strange Olympics, Caeleb Dressel knows he can always come home to his wife, his family and his adoring black Lab. Jane doesn’t care how many medals her man wins; she just hopes he’ll take her out for a dog paddle again soon.

More Olympics Coverage:

• Welcome to Our Very Olympic Today Newsletter

• The Top Threats to the USWNT's Quest for Gold

• Q&A: Wrestler Helen Maroulis's Difficult Path Back to the Games

0 Comments