The Hall of Fame writer was paid handsomely to cover Ali and the Olympics. Today he earns chocolate candies for writing about girls hoops—and the comfort and intimacy has lifted him.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

Our story starts at Steak ‘n Shake. And perhaps it’s a fitting beginning, given that this is the fast food chain of choice for so many postgame meals in the Midwest. Inside this particular franchise, on the outskirts of Peoria, Ill., Dave Kindred had offered up his services to the two men seated on the other side of the booth: Bob Becker, who was—and is—the longtime basketball coach of the Morton High Lady Potters; and David Byrne, the father of one of the players, and the team’s webmaster.

This was 2010, and Kindred had just sat in the bleachers, held in a thrall by a Lady Potters game. At 69, he’d seen his share of women’s sports before, often at the highest level. But here he was, transfixed, he says, as five players with mastered fundamentals presented a symphonic whole far greater than the sum of their parts. He had offered a proposal, volunteering his services as a kind of unofficial Potters beat writer. This was something akin to the formal job interview.

Kindred read the room and sensed skepticism. The webmaster would later describe Kindred, playfully, as “this disheveled old man who came out of the stands” offering to write. The coach, too, was apprehensive; he wasn’t sure of the motives behind this person with no obvious connection to the team. And so Kindred uttered a line completely at odds with his default mode of Midwest modesty: “Want to find out if I can spell and type? You can Google me.”

Kindred’s career took flight in the ’60s, when as a cub reporter for the Louisville Courier-Journal he began covering a local fighter one year his junior. Cassius Clay had already won his first heavyweight title, but he was not yet a cultural figure. Kindred would go on to interview Clay—later, of course, Muhammad Ali—more than 300 times, and he sat ringside for most of the champ’s fights.

Ali nicknamed Kindred “Louisville” and treated him with hometown loyalty, granting an audience even if it meant improvising. Before one fight, around 1973, Kindred tried to interview Ali in a crowded Las Vegas hotel suite. Seeking some privacy, Ali invited Kindred into his bedroom. “He raises up the corner of the sheets and says, ‘Get in,’ ” Kindred recalls half a century later. “Well, I don’t know what you do if the heavyweight champion of the world tells you ‘Get in,’ but I did. And one of us had on clothes.”

Kindred admits that covering Ali spoiled him, which will elicit in today’s media a degree of envy, given the limited access to athletes in 2021. “The great thing about interviewing Ali,” he says, “is that you never interviewed him, because he never shut up. He just kept talking. So you just kept writing. In fact, if you weren’t writing, he would call you out. You gettin' this down? This is heavy, man. And so there was never an interrogation. There was never questioning. There was never a conversation. It was basically you just listening to him perform.”

In the ’70s, Kindred continued covering Ali but moved from Louisville to The Washington Post, where he was a featured columnist alongside the likes of Tony Kornheiser and Mike Wilbon. (John Feinstein, a Post colleague, once asserted that Bob Woodward was the best reporter he’d ever witnessed—Dave Kindred was the second.) He did stints at The National, the romanticized sports daily; The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and The Sporting News. All the while, he fashioned himself a reporter first and a writer second. “You know, the stories don’t come to you,” he says. “That was one of [columnist] Red Smith’s lines: Be there. I wanted to be places where things were happening.”

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

For all his reporting chops, Kindred also came to be known as a stylist who managed to find that sweet spot, writing with flair but resisting look-at-me tendencies. One example among countless, here’s how he described Michael Jordan after MJ’s 1999 retirement announcement:

"Mr. Jordan's pose may not have been for history's cameras, but it certainly was his signature, with a flourish, on a masterpiece of the warrior's work. Again, Mr. Ali comes to mind. The night he knocked out Sonny Liston a second time, he signed his work by dancing beside the fallen body, screaming down at the beaten man, his right arm curled up in contempt and conquest."

Kindred spent much of his days on the road, a life defined by the gyrations of the sports calendar. By his reckoning, he’s covered 44 of the 55 Super Bowls and the vast majority of the World Series held over the last half-century, plus 17 of Ali’s fights, and various Olympics. He was there for the Miracle on Ice in 1980. His lead: “On the train to Gettysburg a few seasons back, Abe Lincoln wrote notes for a speech on whatever scrap of paper he could find. It was a nice speech, long remembered. Today a hockey coach, Herb Brooks, scribbled his pep talk on the back of an envelope. And when the coach's young Americans beat the mighty Soviet Union—beat the very best hockey team on earth, 4–3—the telephone rang with a call from the man who now lives in Abe's old house. ‘President Carter said we made the American people very proud,’ Brooks said after the United States' improbable victory ended the Soviets' 21-game winning streak in the Winter Olympics… .”

At the 1996 Games in Atlanta, Kindred was the local columnist, which meant that, in those very-early-Internet days, his peers read his work each morning. And his coverage of the Masters, in one publication or another, goes back to ’67; until COVID-19 hit, he’d been absent just one year. That was in ’86, when Augusta conflicted with the wedding of Kindred’s son, Jeff. Jack Nicklaus, then 46, won dramatically, his 18th and final major—and then he sent Kindred a letter, reassuring the writer that he’d made the right choice in prioritizing family.

By 2010, though, Kindred was a writer in repose. In the span of a few years, he lost “multiple six-figure jobs” and was left to freelance. As he puts it: “It wasn’t as much that I left the sports world as newspapers left the sports world.” Print media was in its spiral of decline and the sports columnist—more interested in fashioning lyrical profiles and accounts than live-tweeting games—had fallen out of vogue with media bean counters, if not the audience.

This, though, wasn’t altogether tragic for Kindred. He and Cheryl, his wife of nearly half a century, would downshift and return to the flat-as-a-basketball-court plains of central Illinois. In the ’50s, they had been high school sweethearts in Atlanta, Ill.—a speck on the map, hard by Route 66, the halfcourt line between St. Louis and Chicago. He was a D-III baseball player whose dreams of starring in the majors shifted to covering them when it became clear that he (unlike his Illinois Wesleyan teammate Doug Rader) couldn’t keep up with 90 mph fastballs. She was smart and popular and also athletic, though there were no teams for which she could play.

Now, finally, Dave and Cheryl could close the circle and return home. Someone else could chase all those deadlines, earn all those Marriott points. In their spacious log cabin, on a sprawling piece of property alongside a pond, they would read and talk and watch the sun set over the prairie with their dog, KO, at their side.

Soon after their arrival, Dave and Cheryl attended a gathering at the home of Kindred’s sister, Sandra. There they met a local teenager—a young, athletic type—and in peppering her with questions, one of the Kindreds asked: “Are you going to be a cheerleader?”

“No,” the girl shot back. “I’m gonna be the one they cheer for.”

Good for her, they thought. Soon after they went to see her play basketball at the Potterdome—grandiosely named, but in reality just another vintage Midwest high school sweatbox where the scent of popcorn hangs in the air, the pep band performs with irony-free earnestness, and various trophies (including, here, for the bass fishing champs) clutter a case in the lobby.

Then and there, Dave Kindred’s professional instincts kicked in—“I couldn’t sit there and not write about what I saw”—which is how he ended up at Steak ‘n Shake, volunteering for a job that didn’t exist. Soon after, the Morton High webmaster came around. And, more important, so did the man who’d been overseeing the Lady Potters program since 1999. “Here I am, a small-town girls basketball coach,” says Becker. “But after that initial shock, after a little bit of research, we've got the Michael Jordan of sportswriting that falls in our lap.”

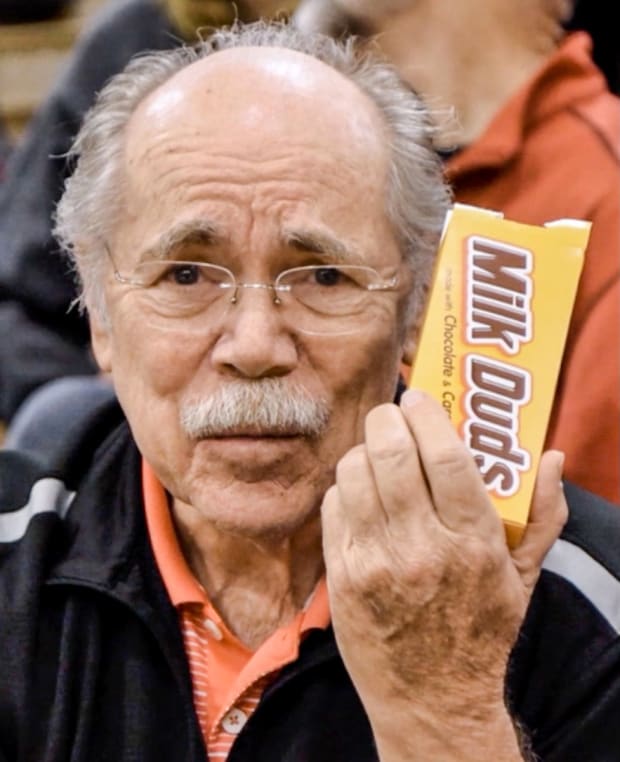

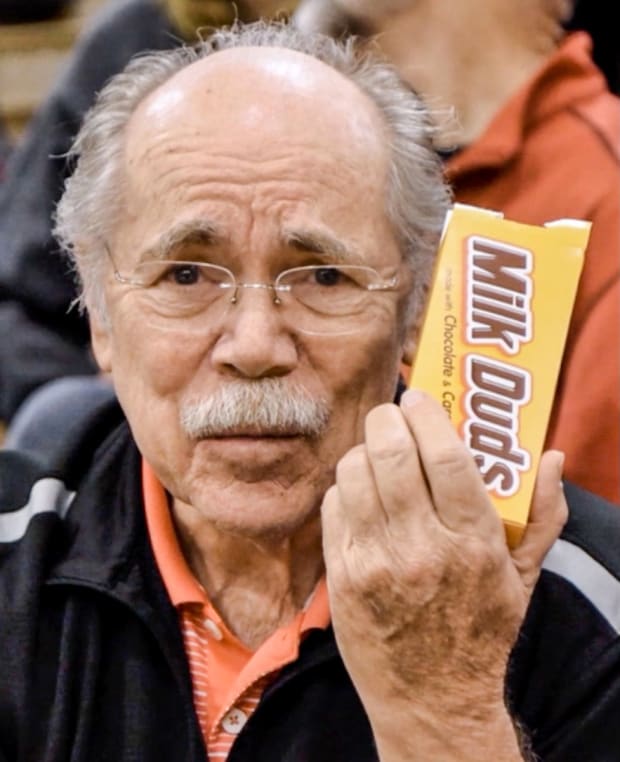

Then it came time to negotiate compensation. "Look, I'm a professional sports writer,” Kindred said. “I should be getting something for doing all this stuff for you."

Tongue firmly embedded in cheek, he recalls what happened next: “They measured my talent and experience and good looks and said, ‘How about a box of Milk Duds every game?’ "

So it began. Kindred would take his position in the bleachers, a few rows back of the bench, often beside Cheryl. Dressed like a prep reporter—ball cap, windbreaker, jeans, boots—he would brandish a notepad, bisect each page with home and visitors columns, and write what he saw and heard.

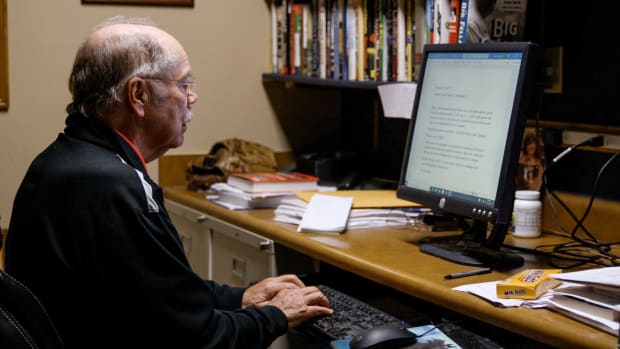

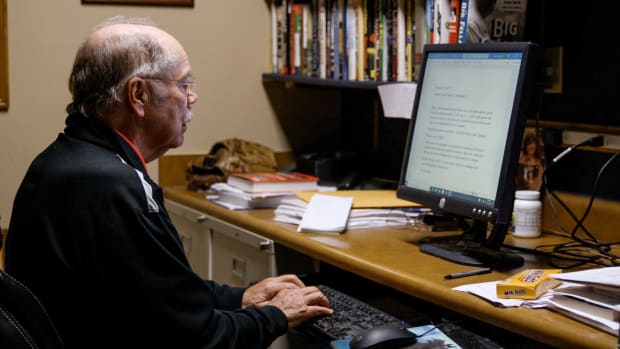

At halftime, he would organize his notes. After the final buzzer, he would confer with the coaches and seek out players for quotes. He would head home, park himself in front of his computer and synthesize it all, trying to paint a picture with his words. In the end, he’d post his write-up on the Potters’ website and on Facebook before heading to sleep. He wasn’t covering the Super Bowl; this was nowhere near Augusta. But, distilled to their essence, his days and his duties were not that different from what he’d been doing since the ’60s.

There were, Kindred says, some differences between this and conventional sportswriting. Freed from the tyranny of editing (this writer’s word, not his), he had to rely on his own judgement as a backstop. Deadline pressure came from restless parents and grandparents, eager to read a write-up before going to bed, but there was no hold-the-presses panic.

The same writer who once described Pete Maravich as “Ichabod Crane on the fast break” was turning his talent to subjects he called “the Golden State Warriors with ponytails.” As he covers games, he remains guided by a simple principle: “If you've been paying attention, you’re going to see something in every event that you have never seen before. ... I wasn’t there to be a character in the story. I was a spectator—and I am going to transmit that spectacle to the reader.”

For several years, the going was good. Then came a triple-team of tragedy. In April 2014, Kindred’s 96-year-old mother, Marie, passed away. Around the same time, Kindred’s grandson Jared died at age 25. The two had been inextricable when Jared was a boy—“I loved him in ways that I never loved anybody,” Kindred says today. But as a teenager Jared grew addicted to drugs and alcohol. He began living on the margins, train-hopping around the country, and substance abuse ultimately led to his death. “Jared didn’t choose to be addicted,” says Kindred. “Addiction chose him.”

Not long after that, Cheryl suffered a stroke. Doctors were unsure of her chances of recovery and, to this day, she remains unable to communicate. Kindred went to the hospital and, with his wife unconscious for days, wondered if he shouldn’t dial back the writing.

The mother of a player talked him out of quitting.

“She said, ‘You gotta go. You gotta go,’ ” Kindred recalls. “And she was right. I went. And I've been going ever since. What had started as fun became life-affirming. It's what I am. It's what I do. … My life had turned dark. [The basketball team was] light. And I knew that light was always gonna be there two or three times a week.”

Long ago, Kindred declined a Super Bowl XVII ring from Washington, the team he was covering, on the grounds that the optics were unseemly. But now, not exactly fearful about ulterior motives, he accepts meals from players’ families and other fans; he says Yes to offers of tech support. Players began accompanying him when he made his daily trip to a convalescent home to see Cheryl. (In June of 2021, Cheryl Kindred passed away at age 79.) His stoic Midwestern demeanor deserts him, his voice catches, when he talks about it all. “This team became a community,” he says. “It became people that I could count on, and it became a reason to get out of the house.”

In the meantime, the Potters would become a basketball powerhouse, the UConn of central Illinois. Becker, one of those teacher-coaches every parent wishes their kids could experience, has enjoyed what in local parlance would be called a “high yield” of both prospects and victories, including four state championships since 2015. (Kindred’s name is engraved on the most recent trophy, alongside players and coaches, credited as the “team blogger.”) Before this pandemic-addled season—with only in-conference games and no state tournament—the Lady Potters had won 201 of their last 215 games. Kindred concedes: If the team, instead, had been 14–201, his enjoyment likely would have been considerably diminished.

Watch Jon Wertheim's interview with Kindred on 60 Minutes

Apart from his dispatches, he also self-publishes (and self-finances) team yearbooks, which he distributes to players and fans after most seasons, and at home he tucks them in alongside his other works, including a (pre-Bezos) requiem for The Washington Post and a dual biography of Ali and Howard Cosell.

If Dave Kindred going home and covering high school hoops is something akin to Woodward uncovering corruption inside a small-town zoning board, the players appreciate the expert journalism. Says Raquel Frakes, a senior guard-forward: “Coach brought him into our circle and introduced him and said all of his accomplishments, his sportswriting with Muhammad Ali and everything. I was, like, ‘Whoa. Why are you in Morton? This is crazy.’ ”

“It's so special that someone that is so good at what he does wants to be here and write about us,” says guard Maggie Hobson, a rising senior. “We're that team for him.”

The Potters’ best player, a junior forward named Katie Krupa who’s committed to Harvard, makes a point of spotting Kindred in the crowd as she goes through the pregame layup line. As she sees it, just as her passion is basketball, his is writing. “I think he wants to be doing it for as long as he possibly can.”

She’s right. Kindred, now 80, knows better than anyone that pitchers lose their fastball, basketball players lose a step and boxers—not least Ali—lose their crispness. He knows that writers, happily, are conferred a more generous life cycle. Seven years in the making, Kindred just published a book about Jared’s itinerant life and tragic death. After Tiger Woods was injured in an automobile accident in February, Golf Digest turned to the old vet for a column. Then there’s the subject of his dispatches for the last decade.

Even in the most recent Potters season, abbreviated by the coronavirus, Kindred took his customary spot in the stands. The small rituals—the pregame Milk Duds, the postgame quotes, the recaps and features posted a few hours after the final horn—were comforting as ever. And while he’s too modest to assess the quality of his work, he does allow himself to marvel at the sheer quantity. “I’ve written more than 300 games, probably more than 500,000 words,” he says. “I've written more about that girls basketball team than I've written about anything—including Ali.”

Surely, as someone who slings stories for a living, he appreciates the richness of this one? He pauses to consider it.

“I came not from Red Smith's generation,” he says, “but the generation after that, where it was almost a journalistic sin to write about yourself. As Red used to call it, ‘the dreaded vertical pronoun.’ So this idea that I understand my story is almost alien, because I never really thought of my story.

“But I'm beginning to think about it.”

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

The Hall of Fame writer was paid handsomely to cover Ali and the Olympics. Today he earns chocolate candies for writing about girls hoops—and the comfort and intimacy has lifted him.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

Our story starts at Steak ‘n Shake. And perhaps it’s a fitting beginning, given that this is the fast food chain of choice for so many postgame meals in the Midwest. Inside this particular franchise, on the outskirts of Peoria, Ill., Dave Kindred had offered up his services to the two men seated on the other side of the booth: Bob Becker, who was—and is—the longtime basketball coach of the Morton High Lady Potters; and David Byrne, the father of one of the players, and the team’s webmaster.

This was 2010, and Kindred had just sat in the bleachers, held in a thrall by a Lady Potters game. At 69, he’d seen his share of women’s sports before, often at the highest level. But here he was, transfixed, he says, as five players with mastered fundamentals presented a symphonic whole far greater than the sum of their parts. He had offered a proposal, volunteering his services as a kind of unofficial Potters beat writer. This was something akin to the formal job interview.

Kindred read the room and sensed skepticism. The webmaster would later describe Kindred, playfully, as “this disheveled old man who came out of the stands” offering to write. The coach, too, was apprehensive; he wasn’t sure of the motives behind this person with no obvious connection to the team. And so Kindred uttered a line completely at odds with his default mode of Midwest modesty: “Want to find out if I can spell and type? You can Google me.”

Googling Dave Kindred would have revealed his identity as an absolute titan of sportswriting. One of the great ironies of his profession: athletes and teams are subject to rankings and scoreboards and standings. It’s a cold and objective business, there for all to scrutinize, almost always yielding a loser for every winner. Sports media, meanwhile, is blazingly subjective. Your Deford or Costas is someone else’s Bayless. Still, by any measure, Kindred was a perennial all-star, a first-ballot Hall of Famer, a long-time columnist and author who laid claim to every sportswriting award obtainable.

Kindred’s career took flight in the ’60s, when as a cub reporter for the Louisville Courier-Journal he began covering a local fighter one year his junior. Cassius Clay had already won his first heavyweight title, but he was not yet a cultural figure. Kindred would go on to interview Clay—later, of course, Muhammad Ali—more than 300 times, and he sat ringside for most of the champ’s fights.

Ali nicknamed Kindred “Louisville” and treated him with hometown loyalty, granting an audience even if it meant improvising. Before one fight, around 1973, Kindred tried to interview Ali in a crowded Las Vegas hotel suite. Seeking some privacy, Ali invited Kindred into his bedroom. “He raises up the corner of the sheets and says, ‘Get in,’ ” Kindred recalls half a century later. “Well, I don’t know what you do if the heavyweight champion of the world tells you ‘Get in,’ but I did. And one of us had on clothes.”

Kindred admits that covering Ali spoiled him, which will elicit in today’s media a degree of envy, given the limited access to athletes in 2021. “The great thing about interviewing Ali,” he says, “is that you never interviewed him, because he never shut up. He just kept talking. So you just kept writing. In fact, if you weren’t writing, he would call you out. You gettin' this down? This is heavy, man. And so there was never an interrogation. There was never questioning. There was never a conversation. It was basically you just listening to him perform.”

In the ’70s, Kindred continued covering Ali but moved from Louisville to The Washington Post, where he was a featured columnist alongside the likes of Tony Kornheiser and Mike Wilbon. (John Feinstein, a Post colleague, once asserted that Bob Woodward was the best reporter he’d ever witnessed—Dave Kindred was the second.) He did stints at The National, the romanticized sports daily; The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and The Sporting News. All the while, he fashioned himself a reporter first and a writer second. “You know, the stories don’t come to you,” he says. “That was one of [columnist] Red Smith’s lines: Be there. I wanted to be places where things were happening.”

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

For all his reporting chops, Kindred also came to be known as a stylist who managed to find that sweet spot, writing with flair but resisting look-at-me tendencies. One example among countless, here’s how he described Michael Jordan after MJ’s 1999 retirement announcement:

"Mr. Jordan's pose may not have been for history's cameras, but it certainly was his signature, with a flourish, on a masterpiece of the warrior's work. Again, Mr. Ali comes to mind. The night he knocked out Sonny Liston a second time, he signed his work by dancing beside the fallen body, screaming down at the beaten man, his right arm curled up in contempt and conquest."

Kindred spent much of his days on the road, a life defined by the gyrations of the sports calendar. By his reckoning, he’s covered 44 of the 55 Super Bowls and the vast majority of the World Series held over the last half-century, plus 17 of Ali’s fights, and various Olympics. He was there for the Miracle on Ice in 1980. His lead: “On the train to Gettysburg a few seasons back, Abe Lincoln wrote notes for a speech on whatever scrap of paper he could find. It was a nice speech, long remembered. Today a hockey coach, Herb Brooks, scribbled his pep talk on the back of an envelope. And when the coach's young Americans beat the mighty Soviet Union—beat the very best hockey team on earth, 4–3—the telephone rang with a call from the man who now lives in Abe's old house. ‘President Carter said we made the American people very proud,’ Brooks said after the United States' improbable victory ended the Soviets' 21-game winning streak in the Winter Olympics… .”

At the 1996 Games in Atlanta, Kindred was the local columnist, which meant that, in those very-early-Internet days, his peers read his work each morning. And his coverage of the Masters, in one publication or another, goes back to ’67; until COVID-19 hit, he’d been absent just one year. That was in ’86, when Augusta conflicted with the wedding of Kindred’s son, Jeff. Jack Nicklaus, then 46, won dramatically, his 18th and final major—and then he sent Kindred a letter, reassuring the writer that he’d made the right choice in prioritizing family.

By 2010, though, Kindred was a writer in repose. In the span of a few years, he lost “multiple six-figure jobs” and was left to freelance. As he puts it: “It wasn’t as much that I left the sports world as newspapers left the sports world.” Print media was in its spiral of decline and the sports columnist—more interested in fashioning lyrical profiles and accounts than live-tweeting games—had fallen out of vogue with media bean counters, if not the audience.

This, though, wasn’t altogether tragic for Kindred. He and Cheryl, his wife of nearly half a century, would downshift and return to the flat-as-a-basketball-court plains of central Illinois. In the ’50s, they had been high school sweethearts in Atlanta, Ill.—a speck on the map, hard by Route 66, the halfcourt line between St. Louis and Chicago. He was a D-III baseball player whose dreams of starring in the majors shifted to covering them when it became clear that he (unlike his Illinois Wesleyan teammate Doug Rader) couldn’t keep up with 90 mph fastballs. She was smart and popular and also athletic, though there were no teams for which she could play.

Now, finally, Dave and Cheryl could close the circle and return home. Someone else could chase all those deadlines, earn all those Marriott points. In their spacious log cabin, on a sprawling piece of property alongside a pond, they would read and talk and watch the sun set over the prairie with their dog, KO, at their side.

Soon after their arrival, Dave and Cheryl attended a gathering at the home of Kindred’s sister, Sandra. There they met a local teenager—a young, athletic type—and in peppering her with questions, one of the Kindreds asked: “Are you going to be a cheerleader?”

“No,” the girl shot back. “I’m gonna be the one they cheer for.”

Good for her, they thought. Soon after they went to see her play basketball at the Potterdome—grandiosely named, but in reality just another vintage Midwest high school sweatbox where the scent of popcorn hangs in the air, the pep band performs with irony-free earnestness, and various trophies (including, here, for the bass fishing champs) clutter a case in the lobby.

Then and there, Dave Kindred’s professional instincts kicked in—“I couldn’t sit there and not write about what I saw”—which is how he ended up at Steak ‘n Shake, volunteering for a job that didn’t exist. Soon after, the Morton High webmaster came around. And, more important, so did the man who’d been overseeing the Lady Potters program since 1999. “Here I am, a small-town girls basketball coach,” says Becker. “But after that initial shock, after a little bit of research, we've got the Michael Jordan of sportswriting that falls in our lap.”

Then it came time to negotiate compensation. "Look, I'm a professional sports writer,” Kindred said. “I should be getting something for doing all this stuff for you."

Tongue firmly embedded in cheek, he recalls what happened next: “They measured my talent and experience and good looks and said, ‘How about a box of Milk Duds every game?’ "

So it began. Kindred would take his position in the bleachers, a few rows back of the bench, often beside Cheryl. Dressed like a prep reporter—ball cap, windbreaker, jeans, boots—he would brandish a notepad, bisect each page with home and visitors columns, and write what he saw and heard.

At halftime, he would organize his notes. After the final buzzer, he would confer with the coaches and seek out players for quotes. He would head home, park himself in front of his computer and synthesize it all, trying to paint a picture with his words. In the end, he’d post his write-up on the Potters’ website and on Facebook before heading to sleep. He wasn’t covering the Super Bowl; this was nowhere near Augusta. But, distilled to their essence, his days and his duties were not that different from what he’d been doing since the ’60s.

There were, Kindred says, some differences between this and conventional sportswriting. Freed from the tyranny of editing (this writer’s word, not his), he had to rely on his own judgement as a backstop. Deadline pressure came from restless parents and grandparents, eager to read a write-up before going to bed, but there was no hold-the-presses panic.

The same writer who once described Pete Maravich as “Ichabod Crane on the fast break” was turning his talent to subjects he called “the Golden State Warriors with ponytails.” As he covers games, he remains guided by a simple principle: “If you've been paying attention, you’re going to see something in every event that you have never seen before. ... I wasn’t there to be a character in the story. I was a spectator—and I am going to transmit that spectacle to the reader.”

For several years, the going was good. Then came a triple-team of tragedy. In April 2014, Kindred’s 96-year-old mother, Marie, passed away. Around the same time, Kindred’s grandson Jared died at age 25. The two had been inextricable when Jared was a boy—“I loved him in ways that I never loved anybody,” Kindred says today. But as a teenager Jared grew addicted to drugs and alcohol. He began living on the margins, train-hopping around the country, and substance abuse ultimately led to his death. “Jared didn’t choose to be addicted,” says Kindred. “Addiction chose him.”

Not long after that, Cheryl suffered a stroke. Doctors were unsure of her chances of recovery and, to this day, she remains unable to communicate. Kindred went to the hospital and, with his wife unconscious for days, wondered if he shouldn’t dial back the writing.

The mother of a player talked him out of quitting.

“She said, ‘You gotta go. You gotta go,’ ” Kindred recalls. “And she was right. I went. And I've been going ever since. What had started as fun became life-affirming. It's what I am. It's what I do. … My life had turned dark. [The basketball team was] light. And I knew that light was always gonna be there two or three times a week.”

Long ago, Kindred declined a Super Bowl XVII ring from Washington, the team he was covering, on the grounds that the optics were unseemly. But now, not exactly fearful about ulterior motives, he accepts meals from players’ families and other fans; he says Yes to offers of tech support. Players began accompanying him when he made his daily trip to a convalescent home to see Cheryl. (In June of 2021, Cheryl Kindred passed away at age 79.) His stoic Midwestern demeanor deserts him, his voice catches, when he talks about it all. “This team became a community,” he says. “It became people that I could count on, and it became a reason to get out of the house.”

In the meantime, the Potters would become a basketball powerhouse, the UConn of central Illinois. Becker, one of those teacher-coaches every parent wishes their kids could experience, has enjoyed what in local parlance would be called a “high yield” of both prospects and victories, including four state championships since 2015. (Kindred’s name is engraved on the most recent trophy, alongside players and coaches, credited as the “team blogger.”) Before this pandemic-addled season—with only in-conference games and no state tournament—the Lady Potters had won 201 of their last 215 games. Kindred concedes: If the team, instead, had been 14–201, his enjoyment likely would have been considerably diminished.

Watch Jon Wertheim's interview with Kindred on 60 Minutes

Apart from his dispatches, he also self-publishes (and self-finances) team yearbooks, which he distributes to players and fans after most seasons, and at home he tucks them in alongside his other works, including a (pre-Bezos) requiem for The Washington Post and a dual biography of Ali and Howard Cosell.

If Dave Kindred going home and covering high school hoops is something akin to Woodward uncovering corruption inside a small-town zoning board, the players appreciate the expert journalism. Says Raquel Frakes, a senior guard-forward: “Coach brought him into our circle and introduced him and said all of his accomplishments, his sportswriting with Muhammad Ali and everything. I was, like, ‘Whoa. Why are you in Morton? This is crazy.’ ”

“It's so special that someone that is so good at what he does wants to be here and write about us,” says guard Maggie Hobson, a rising senior. “We're that team for him.”

The Potters’ best player, a junior forward named Katie Krupa who’s committed to Harvard, makes a point of spotting Kindred in the crowd as she goes through the pregame layup line. As she sees it, just as her passion is basketball, his is writing. “I think he wants to be doing it for as long as he possibly can.”

She’s right. Kindred, now 80, knows better than anyone that pitchers lose their fastball, basketball players lose a step and boxers—not least Ali—lose their crispness. He knows that writers, happily, are conferred a more generous life cycle. Seven years in the making, Kindred just published a book about Jared’s itinerant life and tragic death. After Tiger Woods was injured in an automobile accident in February, Golf Digest turned to the old vet for a column. Then there’s the subject of his dispatches for the last decade.

Even in the most recent Potters season, abbreviated by the coronavirus, Kindred took his customary spot in the stands. The small rituals—the pregame Milk Duds, the postgame quotes, the recaps and features posted a few hours after the final horn—were comforting as ever. And while he’s too modest to assess the quality of his work, he does allow himself to marvel at the sheer quantity. “I’ve written more than 300 games, probably more than 500,000 words,” he says. “I've written more about that girls basketball team than I've written about anything—including Ali.”

Surely, as someone who slings stories for a living, he appreciates the richness of this one? He pauses to consider it.

“I came not from Red Smith's generation,” he says, “but the generation after that, where it was almost a journalistic sin to write about yourself. As Red used to call it, ‘the dreaded vertical pronoun.’ So this idea that I understand my story is almost alien, because I never really thought of my story.

“But I'm beginning to think about it.”

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

0 Comments