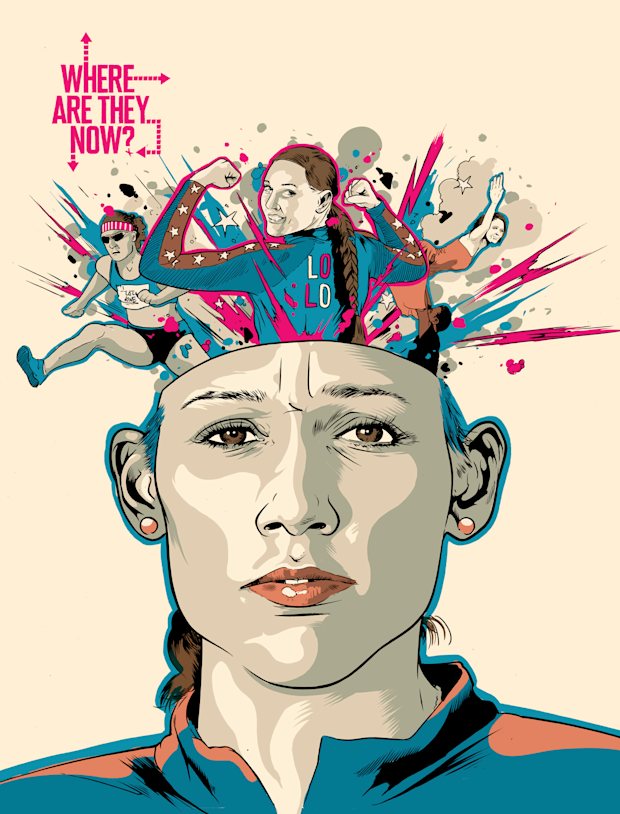

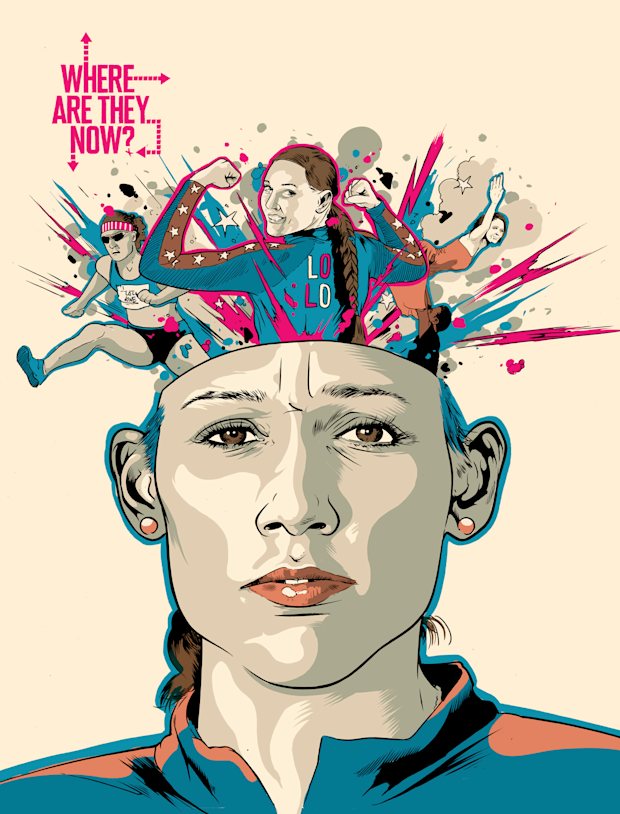

The hurdler didn’t let her crushing defeat at the 2008 Olympics break her spirit—instead, in the decade-plus since, she's been one of the most voracious competitors on the planet, carving out careers in bobsled and reality television in search of another win.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

It was the morning after a shocking defeat, and Lolo Jones was near tears.

“Whenever I go through something tough, I always try to learn something, take away something,” Jones told Good Morning America. “I sulked. I was having a hard time breathing.”

Jones was not new to crushing loss. She’d been a world-class athlete since her LSU days, after all. She was new, however, to this kind of loss. This wasn’t a failure to medal at a Summer or Winter Olympics; no, Jones had just been booted on the first week from Dancing With the Stars and was taking it as hard as she would any Olympic defeat.

“Trust me, I wanted to have fun,” she says now. “But … already people are like, ‘Oh, she’s lost another thing.’ ”

Jones is not just one of the world’s fastest-ever hurdlers and a decidedly amateur dancer. She’s a master of reinvention: a world-champion bobsledder, a star on franchises like Big Brother and The Challenge, an Instagram influencer and an author, too. (Her memoir, Over It: How to Face Life’s Hurdles With Grit, Hustle, and Grace, will come out July 20.) Yet she’s not just an older athlete looking for a second (or third or fourth) act, or a provocateur desperately trying to stay relevant at all costs: She occupies the space somewhere in between, searching earnestly for meaning and glory in her career.

More than a decade after Jones rose to international fame at the Beijing Games in light of a heartbreaking defeat, she is training to return to the Celestial City. This time, though, for her second Winter Olympics in bobsledding. Qualifying starts in July. Jones is 38.

What makes Jones go is one thing that makes her hated in certain circles: her persistence—or, in less kind terms, her stubbornness. She cuts herself no slack.

“I think all my biggest failures are definitely my turning points,” she says.

Jones’s first failure, she says, was missing the cut for the 2004 Olympic team. But her biggest, most public one by far came in ’08 in Beijing, where, leading late in the finals of the 100-meter hurdles, she clipped the ninth of 10 and finished seventh instead of earning the gold she was the favorite to win.

She then put on a master class about how to lose gracefully. “It’s the hurdles,” Jones told The New York Times half an hour after peeling herself off the track. “You have to get over all 10 and if you can’t, you’re not meant to be the champion. Today I was not meant to be the champion.” She says the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee now shows athletes how to handle loss by pointing to her example in media training sessions.

That night in the athletes’ village, she couldn’t sleep. She got a text from Angela Whyte, a Canadian hurdler who missed the cut for the final—her own devastating blow. “I was like, ‘Yo, are you O.K.?’ ” Whyte recalls. The two checked out a basketball in Canada’s area and took turns hoisting it at the rim of a hoop near the game room, chatting about their missed shots there and elsewhere at the Games. “We both sucked,” Jones says, laughing. “And I was like, ‘I can’t even win at this, either.’ ”

They stopped around 4:30 a.m., and Jones finally passed out a few hours later. But the fall wasn’t something she could laugh off for good; she’d learn by the next year that it had created a pit inside her that she just couldn’t shake. She relived the moment constantly, while washing dishes and even while asleep. In 2009, Jones was diagnosed with PTSD, something she thought affected only soldiers. “Losing your dream in front of millions of people, and people are now either criticizing you on social media or teasing you or mocking you or feel bad for you,” she says. “I go to the grocery store, like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I feel so bad for you.’ ”

On and off over the years, as she relieved in the 2020 HBO documentary The Weight of Gold, Jones also experienced passive suicidal thoughts. She’d be driving down the highway and hoping a truck hit her, she says. Each Olympics she competed in, where she didn’t bring home a medal and was ridiculed for it both on social media and in the press, would magnify her pain. Even as recently as during COVID-19, quarantining alone in Baton Rouge before adopting a pandemic pup, the goldendoodle Loki, she spiraled into depression at the thought that her career might have ended due to factors outside her control.

“When I hit that hurdle, I became America’s sweetheart,” Jones says. “Like, people felt really bad for me. Well, the more fame you have, the [more] you can fall, because you’re never going to live up to anybody’s expectations. ”

By the time the 2012 Olympics came, the media’s obsession with Jones had long grated on some, including her own U.S. teammates. But it was Jeré Longman, a longtime New York Times sportswriter, who pushed the perception of her as vapid and attention-seeking past its tipping point just two days before Jones’s 100-meter hurdles qualifying heat. In an Aug. 4 article titled

“For Lolo Jones, Everything Is Image,” he wrote:Jones has received far greater publicity than any other American track and field athlete competing in the London Games. This was based not on achievement but on her exotic beauty and on a sad and cynical marketing campaign. Essentially, Jones has decided she will be whatever anyone wants her to be — vixen, virgin, victim — to draw attention to herself and the many products she endorses.

Longman then positioned her virginity, which is part of her Christian identity, as at odds with her having posed nude for ESPN the Magazine’s iconic Body Issue—in which many athletes of all genders did the same—three years earlier. He also characterized her openness about growing up in poverty as a ploy for attention.

Jones cried on Today after reading the piece. Then she finished one-tenth of a second shy of the podium in the hurdle final. “You read a piece in The New York Times that complains that you’re a hot slut who’s, you know, like, a person who looks like a slut but isn’t actually putting out and also are being too open about your own really inspirational story,” says writer Gabriel Mac, who criticized Longman’s article for Reuters in 2012. “It’s so gross … and dehumanizing.”

The childhood struggles Longman weaponized are well-documented. They make up possibly the most oft-recited downtrodden U.S. Olympic backstory. Jones’s family grew up poor, with her dad in prison. She learned to shoplift food to make do. She was homeless for a time, living with her mother and siblings in a Des Moines church basement. She also lived with other families throughout high school as her family moved, so she could stay put and keep her track dream alive.

“She’s running away from her old life in a way, running toward a different path,” says Rory Karpf, who directed 2012’s SEC Storied episode on Jones in the leadup to that year’s Olympics. “I don’t think that’s ever left her, this feeling that maybe she could wake up and, you know, go back to that life.”

Indeed, money is important to Jones, who says she’s finished years spending thousands more than she’s earned. She brought in nothing her first year as a pro and just $7,500 from a Nike sponsorship the year after. In good years, though, she netted hundreds of thousands of dollars from a combination of sponsors and prize money. Hurdling, she says, isn’t nearly as lucrative as sprinting, which can see contracts in the ballpark of $1 million for top competitors not quite in the Usain Bolt tier.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Jones’s hurdling teammates took notice of her relative renown off the track. “I just felt as if I worked really hard to represent my country [in 2008] in the best way possible,” U.S. Olympic teammate Dawn Harper said in ’12, “and to come away with the gold medal, and to honestly seem as if, because [the media’s] favorite didn’t win all of sudden it’s just like, ‘We’re going to push your story aside, and still gonna push this one.’ ” The frustration was never with Jones herself, says another teammate, Kellie Wells-Brinkley, who took bronze in London. Rather, it was with the media for favoring Jones, a lighter-skinned woman, even as her darker-skinned teammates were medaling. “It’s definitely color,” says Wells-Brinkley. “You know, she’s beautiful. She is. She meets all the criteria, especially back in ’12, commercially to the eye.”

For her part, Jones enjoys promoting herself and seeking attention. She was a fairly early Twitter adopter, joining in August 2009, when most athletes shuddered at the thought of branding themselves on social media. To Longman’s note of Jones’s “exotic beauty,” she says being biracial has hurt her image at times. “You know, a lot of people were just like, ‘Oh, she’s getting my sponsorships because she’s mixed. She’s light-skinned with green eyes,’ ” Jones says. In ’12, two years after her latest World Indoor Championship title and entering her second Olympics, she had seven sponsors; many track and field athletes struggle to secure just one. Even on Instagram today, she frequently hawks for brands including Pedialyte, TopGolf and Abide, a Christian meditation app.

She’s also a seasoned reality star—for the paychecks, she says. (Her agent declined to disclose her earnings, citing confidentiality clauses.) She notes that Dancing With the Stars came after her 2014 Winter Olympics, when she failed to medal in bobsledding and didn’t know whether Asics, her shoe company, would re-sign her. (It did.) When she did Celebrity Big Brother, finishing third, she had lost two sponsors that year. Last year, she did The Challenge, competing (and losing, and apparently quitting) against lesser, uh, athletes, after she missed out on the opportunity to race in track and field—and win prize money—due to the coronavirus pandemic. It beats her early-career jobs at Home Depot and a gym.

For all Jones’s time in the spotlight, she considers herself only a D-list celebrity and insists, only somewhat convincingly, that she doesn’t enjoy the fame. She deflects whenever she’s asked about it, much like she deflected the conversation away from her pain over losing that night on the basketball court in Beijing. “It’s never fun [signing] autographs right next to the super plus plus [tampons],” she says of being famous, laughing. That’s why bobsledding, which she took back up after leaving The Challenge—she swears she didn’t quit, though that’s how the show portrayed her exit—and its relative lack of notoriety is a respite.

Part of what drives Jones to keep reinventing herself is anxiety surrounding money and her firsthand experience knowing that it’s tough to make ends meet year after year. But part of it’s also to prove—to herself but also maybe to her hecklers—that she is, if not always a winner, then at least somebody unwilling to lose.

In early February in Altenberg, Germany, Jones did win. She became a bobsled world champion, as the brakewoman for Kaillie Humphries. She refused to stand on the podium, though. They achieved a two-woman victory, but only one athlete was allowed to bask in the glory, per pandemic restrictions.

“I told her to go up and she said, ‘Absolutely not. You need to go for the pictures,’ ” says Humphries. “And I was like, ‘No, you should go. I won worlds even the year before.’ And this was her first world championships in the winter side.” But Jones didn’t relent.

She insists she’s never been one for the spotlight—dating back to the time she never got asked to prom. (She asked a boy to go with her, but he was focused on flirting with his ex, so she left early.) “If you would have told me in high school I was going to grace the covers of magazines, I would probably have laughed, because I considered myself pretty ugly,” Jones says. “I had acne. I had a gap in my teeth.”

Even now, Jones says, “it’s not about the cameras. It’s not about this and that.” She found bobsled’s 16- to 18-hour days, including time spent working in the grimy garage, humbling. One day in June, she dropped a weight on her toe while training and had to take time off. The last time she competed in the sport, in 2018, she developed seven ulcers, following the stress of three concussions and what she considered an inadequate concussion protocol.

Years earlier, when qualifying for the 2014 Sochi Games, Jones was, familiarly, accused of getting attention—and even making the team—because of her looks and personality. “I should have been working harder on gaining Twitter followers than gaining muscle mass,” a competitor for her Olympic slot told USA Today at the time.

Bobsled is not the kind of sport most kids grow up practicing, so the sprint-to-bobsled pipeline extends far beyond Jones. Historically, a large majority of the men’s and women’s national bobsled teams have collegiate track and field experience. Many athletes reportedly take part in a word-of-mouth combine before ever stepping foot into a sled at the Lake Placid rookie camp.

One of 10 U.S. athletes to compete in both the Summer and Winter Games, Jones came a long way to even qualify for worlds this year alongside her more decorated teammate. Before the pandemic, she had been out of bobsledding for a couple of years and was training for track. When Humphries slid into her Instagram DMs urging her to compete in bobsled instead (“Essentially, it was like Usain Bolt asking me to be on a relay team”), Jones took months to weigh the decision. COVID-19 helped, delaying the Tokyo Games, which she viewed as her last shot at a hurdling comeback on the big stage. She said yes to Humphries, knowing that nothing about her success in the sport was guaranteed.

When asked why Jones keeps returning to athletic competition and, more broadly, reinventing herself, Paulie Calafiore, a fellow Big Brother and Challenge regular, poses a question of his own: “Why does Tom Brady keep going back to the NFL?” he asks. “He is only programmed to outdo himself and to win. Lolo Jones is the same.”

Calafiore is doing something of a reverse-Lolo, seeking to migrate from a career in reality TV shows to Olympic bobsledding. (Perhaps track will follow for the former Rutgers soccer player.) It’s Jones who set up the opportunity for him, though she made sure to warn him to not embarrass her. He’s hoping they’ll make the Games together.

Dennis Shaver, Jones’s track coach at LSU and beyond, “hopes and prays” she’ll get back to Beijing as a bobsledder. He calls their last trip there “a real roller coaster of a week.”

Jones is still competing at an age when she should’ve been thrust into the obscurity of being an anonymous track and field coach somewhere. “That route is coming,” she says.

She’d prefer, though, to be a TV personality, and she’s had a few test runs so far, calling NCAA track and field championships and hosting a show with the Olympic Channel. Jones also interviewed Usain Bolt for EuroSport after he broke the 100-meter world record in 2009. She loves making people laugh, too—even when it gets her into hot water, like when she dressed up as injured Derrick Rose (she was recovering from hip surgery and on crutches herself) or when she poked fun at Drake for hosting the ESPYs and having to hand out awards to Rihanna’s exes.

Getting a job post-retirement makes her nervous. She knows it often takes Olympians a few years to find their footing. But that’s just one more reinvention to add to a lifetime of them, and who’s better suited than Lolo Jones to make a transformation look effortless?

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

The hurdler didn’t let her crushing defeat at the 2008 Olympics break her spirit—instead, in the decade-plus since, she's been one of the most voracious competitors on the planet, carving out careers in bobsled and reality television in search of another win.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

It was the morning after a shocking defeat, and Lolo Jones was near tears.

“Whenever I go through something tough, I always try to learn something, take away something,” Jones told Good Morning America. “I sulked. I was having a hard time breathing.”

Jones was not new to crushing loss. She’d been a world-class athlete since her LSU days, after all. She was new, however, to this kind of loss. This wasn’t a failure to medal at a Summer or Winter Olympics; no, Jones had just been booted on the first week from Dancing With the Stars and was taking it as hard as she would any Olympic defeat.

“Trust me, I wanted to have fun,” she says now. “But … already people are like, ‘Oh, she’s lost another thing.’ ”

Jones is not just one of the world’s fastest-ever hurdlers and a decidedly amateur dancer. She’s a master of reinvention: a world-champion bobsledder, a star on franchises like Big Brother and The Challenge, an Instagram influencer and an author, too. (Her memoir, Over It: How to Face Life’s Hurdles With Grit, Hustle, and Grace, will come out July 20.) Yet she’s not just an older athlete looking for a second (or third or fourth) act, or a provocateur desperately trying to stay relevant at all costs: She occupies the space somewhere in between, searching earnestly for meaning and glory in her career.

More than a decade after Jones rose to international fame at the Beijing Games in light of a heartbreaking defeat, she is training to return to the Celestial City. This time, though, for her second Winter Olympics in bobsledding. Qualifying starts in July. Jones is 38.

What makes Jones go is one thing that makes her hated in certain circles: her persistence—or, in less kind terms, her stubbornness. She cuts herself no slack.

“I think all my biggest failures are definitely my turning points,” she says.

Jones’s first failure, she says, was missing the cut for the 2004 Olympic team. But her biggest, most public one by far came in ’08 in Beijing, where, leading late in the finals of the 100-meter hurdles, she clipped the ninth of 10 and finished seventh instead of earning the gold she was the favorite to win.

She then put on a master class about how to lose gracefully. “It’s the hurdles,” Jones told The New York Times half an hour after peeling herself off the track. “You have to get over all 10 and if you can’t, you’re not meant to be the champion. Today I was not meant to be the champion.” She says the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee now shows athletes how to handle loss by pointing to her example in media training sessions.

That night in the athletes’ village, she couldn’t sleep. She got a text from Angela Whyte, a Canadian hurdler who missed the cut for the final—her own devastating blow. “I was like, ‘Yo, are you O.K.?’ ” Whyte recalls. The two checked out a basketball in Canada’s area and took turns hoisting it at the rim of a hoop near the game room, chatting about their missed shots there and elsewhere at the Games. “We both sucked,” Jones says, laughing. “And I was like, ‘I can’t even win at this, either.’ ”

They stopped around 4:30 a.m., and Jones finally passed out a few hours later. But the fall wasn’t something she could laugh off for good; she’d learn by the next year that it had created a pit inside her that she just couldn’t shake. She relived the moment constantly, while washing dishes and even while asleep. In 2009, Jones was diagnosed with PTSD, something she thought affected only soldiers. “Losing your dream in front of millions of people, and people are now either criticizing you on social media or teasing you or mocking you or feel bad for you,” she says. “I go to the grocery store, like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I feel so bad for you.’ ”

On and off over the years, as she relieved in the 2020 HBO documentary The Weight of Gold, Jones also experienced passive suicidal thoughts. She’d be driving down the highway and hoping a truck hit her, she says. Each Olympics she competed in, where she didn’t bring home a medal and was ridiculed for it both on social media and in the press, would magnify her pain. Even as recently as during COVID-19, quarantining alone in Baton Rouge before adopting a pandemic pup, the goldendoodle Loki, she spiraled into depression at the thought that her career might have ended due to factors outside her control.

“When I hit that hurdle, I became America’s sweetheart,” Jones says. “Like, people felt really bad for me. Well, the more fame you have, the [more] you can fall, because you’re never going to live up to anybody’s expectations. ”

By the time the 2012 Olympics came, the media’s obsession with Jones had long grated on some, including her own U.S. teammates. But it was Jeré Longman, a longtime New York Times sportswriter, who pushed the perception of her as vapid and attention-seeking past its tipping point just two days before Jones’s 100-meter hurdles qualifying heat. In an Aug. 4 article titled “For Lolo Jones, Everything Is Image,” he wrote:

Jones has received far greater publicity than any other American track and field athlete competing in the London Games. This was based not on achievement but on her exotic beauty and on a sad and cynical marketing campaign. Essentially, Jones has decided she will be whatever anyone wants her to be — vixen, virgin, victim — to draw attention to herself and the many products she endorses.

Longman then positioned her virginity, which is part of her Christian identity, as at odds with her having posed nude for ESPN the Magazine’s iconic Body Issue—in which many athletes of all genders did the same—three years earlier. He also characterized her openness about growing up in poverty as a ploy for attention.

Jones cried on Today after reading the piece. Then she finished one-tenth of a second shy of the podium in the hurdle final. “You read a piece in The New York Times that complains that you’re a hot slut who’s, you know, like, a person who looks like a slut but isn’t actually putting out and also are being too open about your own really inspirational story,” says writer Gabriel Mac, who criticized Longman’s article for Reuters in 2012. “It’s so gross … and dehumanizing.”

The childhood struggles Longman weaponized are well-documented. They make up possibly the most oft-recited downtrodden U.S. Olympic backstory. Jones’s family grew up poor, with her dad in prison. She learned to shoplift food to make do. She was homeless for a time, living with her mother and siblings in a Des Moines church basement. She also lived with other families throughout high school as her family moved, so she could stay put and keep her track dream alive.

“She’s running away from her old life in a way, running toward a different path,” says Rory Karpf, who directed 2012’s SEC Storied episode on Jones in the leadup to that year’s Olympics. “I don’t think that’s ever left her, this feeling that maybe she could wake up and, you know, go back to that life.”

Indeed, money is important to Jones, who says she’s finished years spending thousands more than she’s earned. She brought in nothing her first year as a pro and just $7,500 from a Nike sponsorship the year after. In good years, though, she netted hundreds of thousands of dollars from a combination of sponsors and prize money. Hurdling, she says, isn’t nearly as lucrative as sprinting, which can see contracts in the ballpark of $1 million for top competitors not quite in the Usain Bolt tier.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Jones’s hurdling teammates took notice of her relative renown off the track. “I just felt as if I worked really hard to represent my country [in 2008] in the best way possible,” U.S. Olympic teammate Dawn Harper said in ’12, “and to come away with the gold medal, and to honestly seem as if, because [the media’s] favorite didn’t win all of sudden it’s just like, ‘We’re going to push your story aside, and still gonna push this one.’ ” The frustration was never with Jones herself, says another teammate, Kellie Wells-Brinkley, who took bronze in London. Rather, it was with the media for favoring Jones, a lighter-skinned woman, even as her darker-skinned teammates were medaling. “It’s definitely color,” says Wells-Brinkley. “You know, she’s beautiful. She is. She meets all the criteria, especially back in ’12, commercially to the eye.”

For her part, Jones enjoys promoting herself and seeking attention. She was a fairly early Twitter adopter, joining in August 2009, when most athletes shuddered at the thought of branding themselves on social media. To Longman’s note of Jones’s “exotic beauty,” she says being biracial has hurt her image at times. “You know, a lot of people were just like, ‘Oh, she’s getting my sponsorships because she’s mixed. She’s light-skinned with green eyes,’ ” Jones says. In ’12, two years after her latest World Indoor Championship title and entering her second Olympics, she had seven sponsors; many track and field athletes struggle to secure just one. Even on Instagram today, she frequently hawks for brands including Pedialyte, TopGolf and Abide, a Christian meditation app.

She’s also a seasoned reality star—for the paychecks, she says. (Her agent declined to disclose her earnings, citing confidentiality clauses.) She notes that Dancing With the Stars came after her 2014 Winter Olympics, when she failed to medal in bobsledding and didn’t know whether Asics, her shoe company, would re-sign her. (It did.) When she did Celebrity Big Brother, finishing third, she had lost two sponsors that year. Last year, she did The Challenge, competing (and losing, and apparently quitting) against lesser, uh, athletes, after she missed out on the opportunity to race in track and field—and win prize money—due to the coronavirus pandemic. It beats her early-career jobs at Home Depot and a gym.

For all Jones’s time in the spotlight, she considers herself only a D-list celebrity and insists, only somewhat convincingly, that she doesn’t enjoy the fame. She deflects whenever she’s asked about it, much like she deflected the conversation away from her pain over losing that night on the basketball court in Beijing. “It’s never fun [signing] autographs right next to the super plus plus [tampons],” she says of being famous, laughing. That’s why bobsledding, which she took back up after leaving The Challenge—she swears she didn’t quit, though that’s how the show portrayed her exit—and its relative lack of notoriety is a respite.

Part of what drives Jones to keep reinventing herself is anxiety surrounding money and her firsthand experience knowing that it’s tough to make ends meet year after year. But part of it’s also to prove—to herself but also maybe to her hecklers—that she is, if not always a winner, then at least somebody unwilling to lose.

In early February in Altenberg, Germany, Jones did win. She became a bobsled world champion, as the brakewoman for Kaillie Humphries. She refused to stand on the podium, though. They achieved a two-woman victory, but only one athlete was allowed to bask in the glory, per pandemic restrictions.

“I told her to go up and she said, ‘Absolutely not. You need to go for the pictures,’ ” says Humphries. “And I was like, ‘No, you should go. I won worlds even the year before.’ And this was her first world championships in the winter side.” But Jones didn’t relent.

She insists she’s never been one for the spotlight—dating back to the time she never got asked to prom. (She asked a boy to go with her, but he was focused on flirting with his ex, so she left early.) “If you would have told me in high school I was going to grace the covers of magazines, I would probably have laughed, because I considered myself pretty ugly,” Jones says. “I had acne. I had a gap in my teeth.”

Even now, Jones says, “it’s not about the cameras. It’s not about this and that.” She found bobsled’s 16- to 18-hour days, including time spent working in the grimy garage, humbling. One day in June, she dropped a weight on her toe while training and had to take time off. The last time she competed in the sport, in 2018, she developed seven ulcers, following the stress of three concussions and what she considered an inadequate concussion protocol.

Years earlier, when qualifying for the 2014 Sochi Games, Jones was, familiarly, accused of getting attention—and even making the team—because of her looks and personality. “I should have been working harder on gaining Twitter followers than gaining muscle mass,” a competitor for her Olympic slot told USA Today at the time.

Bobsled is not the kind of sport most kids grow up practicing, so the sprint-to-bobsled pipeline extends far beyond Jones. Historically, a large majority of the men’s and women’s national bobsled teams have collegiate track and field experience. Many athletes reportedly take part in a word-of-mouth combine before ever stepping foot into a sled at the Lake Placid rookie camp.

One of 10 U.S. athletes to compete in both the Summer and Winter Games, Jones came a long way to even qualify for worlds this year alongside her more decorated teammate. Before the pandemic, she had been out of bobsledding for a couple of years and was training for track. When Humphries slid into her Instagram DMs urging her to compete in bobsled instead (“Essentially, it was like Usain Bolt asking me to be on a relay team”), Jones took months to weigh the decision. COVID-19 helped, delaying the Tokyo Games, which she viewed as her last shot at a hurdling comeback on the big stage. She said yes to Humphries, knowing that nothing about her success in the sport was guaranteed.

When asked why Jones keeps returning to athletic competition and, more broadly, reinventing herself, Paulie Calafiore, a fellow Big Brother and Challenge regular, poses a question of his own: “Why does Tom Brady keep going back to the NFL?” he asks. “He is only programmed to outdo himself and to win. Lolo Jones is the same.”

Calafiore is doing something of a reverse-Lolo, seeking to migrate from a career in reality TV shows to Olympic bobsledding. (Perhaps track will follow for the former Rutgers soccer player.) It’s Jones who set up the opportunity for him, though she made sure to warn him to not embarrass her. He’s hoping they’ll make the Games together.

Dennis Shaver, Jones’s track coach at LSU and beyond, “hopes and prays” she’ll get back to Beijing as a bobsledder. He calls their last trip there “a real roller coaster of a week.”

Jones is still competing at an age when she should’ve been thrust into the obscurity of being an anonymous track and field coach somewhere. “That route is coming,” she says.

She’d prefer, though, to be a TV personality, and she’s had a few test runs so far, calling NCAA track and field championships and hosting a show with the Olympic Channel. Jones also interviewed Usain Bolt for EuroSport after he broke the 100-meter world record in 2009. She loves making people laugh, too—even when it gets her into hot water, like when she dressed up as injured Derrick Rose (she was recovering from hip surgery and on crutches herself) or when she poked fun at Drake for hosting the ESPYs and having to hand out awards to Rihanna’s exes.

Getting a job post-retirement makes her nervous. She knows it often takes Olympians a few years to find their footing. But that’s just one more reinvention to add to a lifetime of them, and who’s better suited than Lolo Jones to make a transformation look effortless?

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

0 Comments