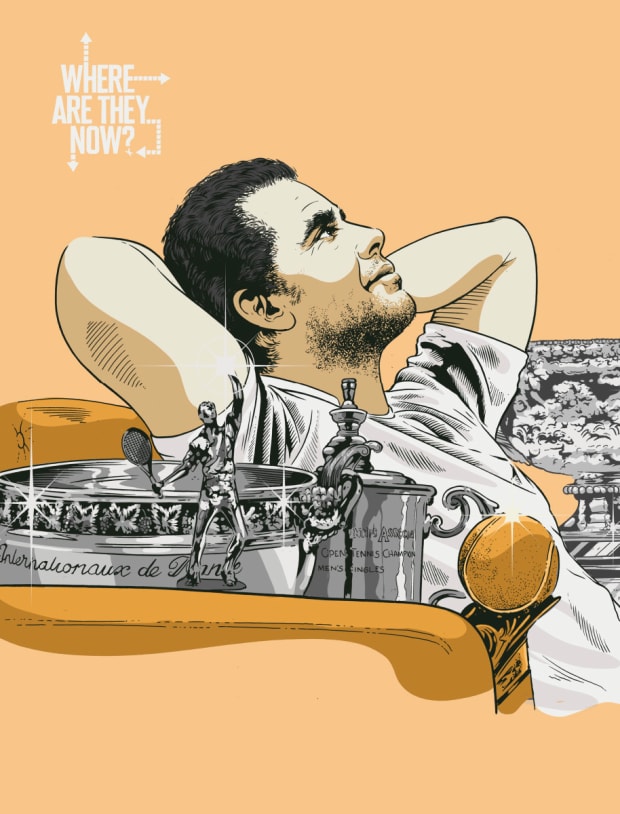

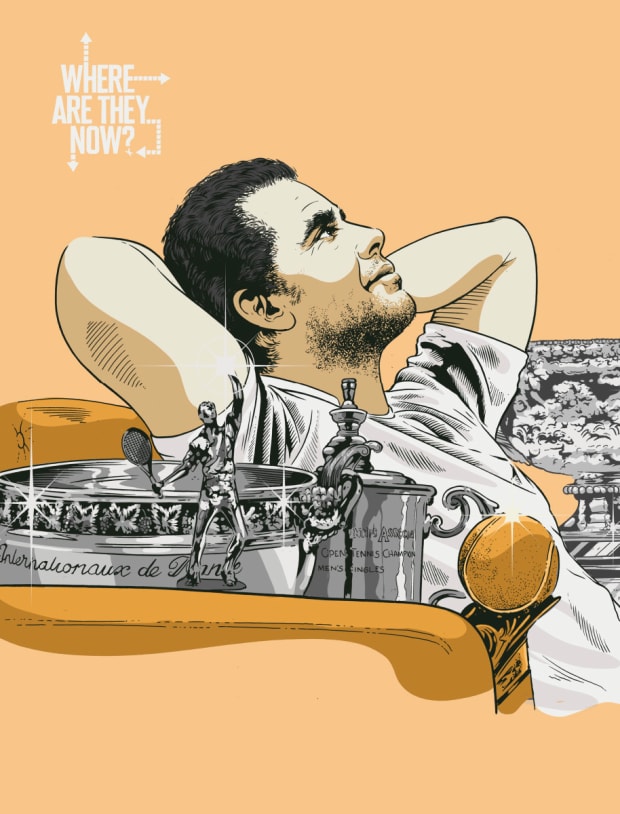

The tennis great doesn't seem to care about the spotlight—or the records he once held.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

Over the last, say, quarter century, tennis has undergone plenty of changes. Those line calls that players once disputed at length? They’re largely gone—officiating is now done largely by automation and artificial intelligence, muting controversy and, some would say, bleaching so much color from the sport. Tennis’s gravitational center has shifted from the United States to Europe. In the 1990s, Americans made up half the ATP’s top ten; and as we write this, there are zero U.S. men in the top 30. The rackets of the ’90s might as well be wooden truncheons, so rapidly has equipment evolved. Armed with space-age material, today’s players are encouraged to devote maximum power to each shot.

There are a few tennis constants: those Williams sisters are still, improbably, at it with their combined age exceeding 80. There is also the unchanged constitution of Pete Sampras. At the peak of his considerable powers, Sampras was an exquisite player. Period. He had no interest in the celebrity aspect of the job. He enjoyed press conferences, glad-handing sponsor parties, promotional appearances and the other duties that attend being a superstar, much the same way cats enjoy bathing.

There was never anything nasty, entitled or egotistical about it. Quite the opposite. Sampras said “no” often, but he did so with a certain manner that made you respect his choice. But to the frustration of so many—agents, tournaments and the ATP Tour itself—Sampras complemented his maximal tennis with minimal publicity. Before the term had yet to infect the vernacular, Sampras was the GOAT. But with the public disposition of a turtle.

Today, the great Pete Sampras is a few months from turning 50. He is within a few pounds of his playing weight of 170 lbs. He still speaks in the same slow, rolling cadences, all sheepishness and modesty and self-deprecating observations. And he remains strenuously, willfully opposed to being a public figure. Even in the sport that is famously good at taking care of its own—lavishing them with a lifetime’s worth of jobs and income-bearing appearances—Sampras does not shill for products, does not show up at many events and does not hear the siren song of the commentary booth.

And to really sling some understatement, he does put himself out there on social media. @PeteSampras joined Twitter in July 2009. A dead giveaway that someone from his team set up the account, the bio I.D.’s Sampras as “14-time Grand Slam Tennis Champion,” at once factually accurate and wildly out of character in its boastfulness. @PeteSampras follows one other account and, though it has 16.8K followers, has yet to post a tweet.

Sampras has been a cordial acquaintance for decades. But approached to speak for this story, Sampras waffled for weeks. Emails went unreturned. A mutual friend suggested offering Sampras a relaxed, off-the-record session. When it was explained that this would defeat the purpose, he predicted, “Are you kidding? Talk about himself? With you reporting and recording? This is exactly the kind of thing Pete doesn’t want to do.” Adds Todd Martin, a Sampras contemporary, now CEO of the International Tennis Hall of Fame: “Pete has always been super, super-protective of his time. That hasn’t changed just because he’s no longer playing.”

Pete’s longtime agent (and longer-time big brother), Gus Sampras, was placed in the familiar role of making an honest effort to broker an interview to only report back, go dark, finally make clear Pete’s going to pass. Politely as ever. On-brand as ever.

It’s the moldiest of sports clichés, this idea of “going out on top.” Yet it remains this cinematic ideal, athletes leaving at the peak of their power, departing (another cliché) on their own terms. In the line of work defined by the binary of wins and losses, your ending moment—and, you’d like to think, the enduring moment for the fans —is that of you, arms aloft. Victory is mine.

No athlete can be blamed for wanting to lick the bottom of the glass, to stay onstage as long as possible. Still, if you wanted to exit gracefully, stylishly from on high, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better exponent than Pete Sampras. In the late summer of 2002, he came to the U.S. Open as a champion in name only. He had just turned 31, which, at the time, was downright geriatric in tennis years. He was ranked No. 17, 16 spots below his standard. He had gone 33 straight events without winning the title. At the previous major, Wimbledon—the lawns he dominated for a full decade—Sampras was exiled to an outside court to play his second-round match, where he promptly lost to a journeyman.

During that defeat, he’d spent changeovers seeking inspiration by reading letters his wife had written him. This drew the mockery of other players. Privately—of course, privately—Sampras insisted he had some good tennis left in him: but the ranks of true believers were thinning.

And then for those two weeks in New York, it was as if Sampras had been teleported to his prime years. He hit with precision and power, and projected self-belief. The legacy of that beautiful motion, his serves found their targets. He showed his familiar fighting spirit, an on-court disposition so at odds with his fiercely casual and laid-back disposition away from tennis. In a who-writes-these-scripts-anyway? final, he faced Andre Agassi, a yin to Sampras’s yang since their days in the juniors. A final bit of punctuation on their rivalry, Sampras won 6–3, 6–4, 5–7, 6–4.

From the early days of his career, Sampras played for posterity. Two years prior, he had won his 13th career major singles title at Wimbledon, setting an all-time record. But this 14th major sealed his bona fides. In the tournament recap, Sports Illustrated flatly—and quite reasonably—declared him “the greatest man ever to play the game.”

Sampras had not only set the benchmark; he had taken it to a place where it seemed like one of those untouchable sports records on the order of, say, Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game or Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak. For perspective, John McEnroe—the great John McEnroe—retired from tennis with seven majors; Agassi, another Mount Rushmore player, had seven at the time as well. Someone was really going to top fourteen? On what planet?

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Beyond the match, the tournament and history, Sampras won something else that day: the affections of the public. For years he was admired, not adored. His career-long disdain for publicity came at a time when sports fans were beginning to seek more than mere excellence from their sports heroes. Here was Sampras, winning clinically but never revealing himself by letting down the drawbridge on his life. Even when he played, Sampras did so with his head down. (“I’m looking for coins,” he quipped, a nod to the sense of humor his confidantes have always sworn was part of Sampras’s personality.)

It didn’t help that Sampras’s factory setting of Southern California reserve was thrown into sharp relief by the charisma and energy of his great foil. All neon and frosted tips, Agassi arrived on the scene with all the subtlety of his hometown, Las Vegas. He talked trash and played to the crowd and married (and divorced) movie stars. Even when Agassi evolved into the sport’s wise man, his transformation—the interest in charter schools, the bracingly candid autobiography—still entailed being a public figure. As Agassi often put it, “Pete would never want my life. I would never want his life.”

It wasn’t that Sampras was boring, as it was often and unfairly shorthanded. It wasn’t that he was a jerk. And it certainly wasn’t that he was insecure. If anything, Martin puts it, Sampras had the self-assurance to commit himself to becoming the world’s best tennis player and decline to indulge in anything that wasn’t in service of that. “As uncomfortable as Pete would seem in public, I always got the sense he was as comfortable in his skin as anyone could be.”

That Sunday in New York Sampras was recast, finally, as the fan favorite. He was the underdog, the old guy trying to prove he still had the magic. The majority of the 25,000 fans inside Arthur Ashe Stadium rooted for him. (So did millions of casual sports fans, awaiting the start of the NFL season on CBS immediately after the match.) Sampras sensed this. In a complete lapse in character, he shouted during the match, “That’s what I’m talking about!” The crowd inside Ashe went nuts. When he finally won, he reckoned that he received the loudest ovation of his career.

Capitalizing on this story line, the chance finally to get Sampras his due, organizers lined up a Manhattan media tour for him. Morning shows, drive-time shows and late-night shows. Sampras, ever graciously, declined it all. He flew home to L.A., a contented man, a champion. He never played another professional match.

Starting in his early 30s—when so many of his peers in conventional lines of work were just entering their meaty years—Sampras was off the clock. And he was faithful to his retirement as, previously, he was to his work. After years of keeping a strict schedule, he let his days unspool in the most leisurely way. After years of displacement—threading the world, sleeping in an unending constellation of hotels, living out of bags—he would go months without leaving his sprawling home in Beverly Hills.

In the late 1990s, Sampras spotted Bridgette Wilson while out in Los Angeles, and asked a mutual friend for her number. They married in 2000, a fittingly small and private ceremony, though Elton John was the musical guest. Wilson was an ascending actress, but, to her credit, never felt fully comfortable in Hollywood. As he retired, she dialed back her career as well, and together, they began raising two boys, Christian, born in ’02, and Ryan, born in ’05.

Once he dropped his sons off at school, Sampras might play golf, often at Bel-Air Country Club, where he has been a longtime member. He might play cards with friends. With a tennis court in the backyard, he might pick up a racket as well. (Ryan, 15, is a junior tennis player of some distinction.) He and Bridgette might collect the kids and head to their weekend home near Palm Springs.

“Every time I see him, he seems totally happy,” says Paul Annacone, a Tennis Channel broadcaster and Sampras’s longtime coach, who remains a friend. “He has a really good perspective and view on being a dad and a husband, and he does whatever he wants to do.”

It’s also significant what Sampras hasn’t done in retirement. While his contemporary, Jim Courier, has established himself as one of tennis’s most perceptive analysts, Sampras has shown no interest in commentating. His sister, Stella, is the terrifically successful head women’s tennis coach at UCLA; her brother has shown little interest in coaching a pro player.

With roughly $50 million earned in prize money—and easily double that in Nike money, appearance fees and bonuses—Sampras doesn’t exactly have urgent financial pressure to launch a second career.

For all the stability in his personal life, his historic record has proven to be sadly fragile. Just a few months after Sampras won that supposedly unassailable 14th major, a talented Swiss star with a game not dissimilar to Sampras’s won Wimbledon for the first time. Two years after that, a swashbuckling Spaniard won the French Open for the first time. Three years after that, a steady Serb won the Australian Open for the first time.

At this writing, the three aforementioned players d/b/a the Big Three—Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, respectively—have won 20, 20 and 19 majors. And it’s important to provide the timestamp, because all three are still active, still winning, and by extension, still distancing themselves from Sampras’s mark. (What’s more, each of the Big Three has won the “career slam,” each of four majors, whereas Sampras never claimed the French, played on clay, his worst surface.)

Imagine you’re Sampras, at 31, and after chasing history for your career, you retire atop the mountain. You’re still in your 40s and not once, not twice, but three times other men have summited higher. There are greater sports tragedies, sure. But this is something akin to Michael Jordan—who also played for the last time in the early aughts—being suddenly absent from most GOAT conversations.

But just as he was during his career Sampras has been extraordinarily, even jarringly, gracious about recent history. He’s never gotten worked up about that which he could not change. In 2009, as Federer was poised to win his 15th major, Annacone went golfing with Sampras at Bel-Air, and wanted to see how his former charge was handling the assault of history.

‘“I said, ‘It’s getting close. What do you think?’ ” recalls Annacone.

“It’s pretty amazing!” Sampras replied.

“What do you mean?” pressed Annacone who, ironically, would go on to coach Federer.

“Well,” said Sampras, “I just know how hard it was for me. If anyone else can do it, that’s just too good. That’s amazing!”

Similarly, as Nadal and Djokovic passed Sampras by, he’s given them nothing but praise and respect—and none of it the grudging variety. Says Annacone: “He’s pretty good at checking his ego at the door … most of all I think he gets the emotional fuel that it takes to continually be in the final weekends of majors and generally come through. When he sees these three guys do it, he’s just genuinely tips his cap, like, ‘Well done, guys.’ ”

Just don’t ask him to anoint a single GOAT. “I feel like every decade there’s the guy. Certainly Roger has been the best player. Rafa is up there with him. Djokovic is pushing. So it’s really hard to say. I mean, there’s not one greatest player,” Sampras told me in 2015. He also takes pains not to discount the past. “For five years [Rod Laver] didn't play any majors when he was in his prime, so he could have had over 20 majors.”

Beyond that, Sampras is friendly with all three of the men who have passed him. He has known Federer the longest. They played each other once in pro competition, a memorable passing-the-baton match at Wimbledon in 2001. They have been bracketed together ever since.

A different kind of warmth passes between Sampras and Nadal. They may be separated by language, culture and a dominant hand, but they have found a kind of game-respects-game common ground. They also share an instinct for avoiding the trappings of stardom and would just as soon never leave their families or put on a collared shirt, much less a tux, if they didn’t have to.

Ironically, perhaps, Sampras is also close with Djokovic. The Serbian seeks to involve himself in politics and envisions himself (sometimes to his detriment) as a global figure, and is, unmistakably, more front-facing than Sampras ever was or wants to be. But they’ve bonded over the relentless pursuit of excellence and the joys of parenting two kids. Djokovic spends considerable time in Los Angeles, and has been known to visit Sampras when he does.

Hoping to rekindle memories of Sampras before they fade like an old photo, the longtime tennis writer Steve Flink recently wrote a book titled, fittingly, Pete Sampras: Greatness Revisited. Flink concludes: “He does not sound like he is feeling sorry for himself in the least, nor does he show any resentment towards Roger, Rafa, or Novak. It appears to me that it is quite the opposite; he is proud of what he did, and he still believes he could have competed favorably against anyone in history including Federer, Djokovic, and Nadal. But he also appreciates their greatness and the way all three have represented themselves. He gives them full marks for breaking his record at the Slams.”

In the course of his research, Flink spoke with Sampras about the operatic 2019 Wimbledon final in which Federer held match points but ultimately lost to Djokovic in a match that will have historical implications for decades. (Or so we think, anyway. Perhaps tennis history is not quite as durable as previously thought.) Sampras watched the match with his family and told Flink how wrenching he found it. “He could not stop thinking about it the rest of the day,” recalls Flink, “and his sentiments were twofold— great respect for Djokovic’s grit and determination and sympathy for Federer losing a heartbreaker.”

Like all athletes, Sampras gets asked the predictable question: Do you miss tennis? Sampras has a standard answer: “I miss the game, but I don’t miss the stress of it.” Part of the stress stemmed from the expectation he placed upon himself. Part of the stress also came from being a public figure. “Now,” says Martin, “in some ways he has the ultimate freedom. He doesn’t do anything he doesn’t want to.”

For almost two decades now, Sampras has led a quiet, private, homebound life that might bore some people, Agassi included. But to plenty of others—most important, of course, Sampras himself—it veers close to meeting the definition of charmed. He may no longer hold the all-time majors record. But he went out on top. He hasn’t budged much.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

The tennis great doesn't seem to care about the spotlight—or the records he once held.

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

Over the last, say, quarter century, tennis has undergone plenty of changes. Those line calls that players once disputed at length? They’re largely gone—officiating is now done largely by automation and artificial intelligence, muting controversy and, some would say, bleaching so much color from the sport. Tennis’s gravitational center has shifted from the United States to Europe. In the 1990s, Americans made up half the ATP’s top ten; and as we write this, there are zero U.S. men in the top 30. The rackets of the ’90s might as well be wooden truncheons, so rapidly has equipment evolved. Armed with space-age material, today’s players are encouraged to devote maximum power to each shot.

There are a few tennis constants: those Williams sisters are still, improbably, at it with their combined age exceeding 80. There is also the unchanged constitution of Pete Sampras. At the peak of his considerable powers, Sampras was an exquisite player. Period. He had no interest in the celebrity aspect of the job. He enjoyed press conferences, glad-handing sponsor parties, promotional appearances and the other duties that attend being a superstar, much the same way cats enjoy bathing.

There was never anything nasty, entitled or egotistical about it. Quite the opposite. Sampras said “no” often, but he did so with a certain manner that made you respect his choice. But to the frustration of so many—agents, tournaments and the ATP Tour itself—Sampras complemented his maximal tennis with minimal publicity. Before the term had yet to infect the vernacular, Sampras was the GOAT. But with the public disposition of a turtle.

Today, the great Pete Sampras is a few months from turning 50. He is within a few pounds of his playing weight of 170 lbs. He still speaks in the same slow, rolling cadences, all sheepishness and modesty and self-deprecating observations. And he remains strenuously, willfully opposed to being a public figure. Even in the sport that is famously good at taking care of its own—lavishing them with a lifetime’s worth of jobs and income-bearing appearances—Sampras does not shill for products, does not show up at many events and does not hear the siren song of the commentary booth.

And to really sling some understatement, he does put himself out there on social media. @PeteSampras joined Twitter in July 2009. A dead giveaway that someone from his team set up the account, the bio I.D.’s Sampras as “14-time Grand Slam Tennis Champion,” at once factually accurate and wildly out of character in its boastfulness. @PeteSampras follows one other account and, though it has 16.8K followers, has yet to post a tweet.

Sampras has been a cordial acquaintance for decades. But approached to speak for this story, Sampras waffled for weeks. Emails went unreturned. A mutual friend suggested offering Sampras a relaxed, off-the-record session. When it was explained that this would defeat the purpose, he predicted, “Are you kidding? Talk about himself? With you reporting and recording? This is exactly the kind of thing Pete doesn’t want to do.” Adds Todd Martin, a Sampras contemporary, now CEO of the International Tennis Hall of Fame: “Pete has always been super, super-protective of his time. That hasn’t changed just because he’s no longer playing.”

Pete’s longtime agent (and longer-time big brother), Gus Sampras, was placed in the familiar role of making an honest effort to broker an interview to only report back, go dark, finally make clear Pete’s going to pass. Politely as ever. On-brand as ever.

It’s the moldiest of sports clichés, this idea of “going out on top.” Yet it remains this cinematic ideal, athletes leaving at the peak of their power, departing (another cliché) on their own terms. In the line of work defined by the binary of wins and losses, your ending moment—and, you’d like to think, the enduring moment for the fans —is that of you, arms aloft. Victory is mine.

No athlete can be blamed for wanting to lick the bottom of the glass, to stay onstage as long as possible. Still, if you wanted to exit gracefully, stylishly from on high, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better exponent than Pete Sampras. In the late summer of 2002, he came to the U.S. Open as a champion in name only. He had just turned 31, which, at the time, was downright geriatric in tennis years. He was ranked No. 17, 16 spots below his standard. He had gone 33 straight events without winning the title. At the previous major, Wimbledon—the lawns he dominated for a full decade—Sampras was exiled to an outside court to play his second-round match, where he promptly lost to a journeyman.

During that defeat, he’d spent changeovers seeking inspiration by reading letters his wife had written him. This drew the mockery of other players. Privately—of course, privately—Sampras insisted he had some good tennis left in him: but the ranks of true believers were thinning.

And then for those two weeks in New York, it was as if Sampras had been teleported to his prime years. He hit with precision and power, and projected self-belief. The legacy of that beautiful motion, his serves found their targets. He showed his familiar fighting spirit, an on-court disposition so at odds with his fiercely casual and laid-back disposition away from tennis. In a who-writes-these-scripts-anyway? final, he faced Andre Agassi, a yin to Sampras’s yang since their days in the juniors. A final bit of punctuation on their rivalry, Sampras won 6–3, 6–4, 5–7, 6–4.

From the early days of his career, Sampras played for posterity. Two years prior, he had won his 13th career major singles title at Wimbledon, setting an all-time record. But this 14th major sealed his bona fides. In the tournament recap, Sports Illustrated flatly—and quite reasonably—declared him “the greatest man ever to play the game.”

Sampras had not only set the benchmark; he had taken it to a place where it seemed like one of those untouchable sports records on the order of, say, Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game or Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak. For perspective, John McEnroe—the great John McEnroe—retired from tennis with seven majors; Agassi, another Mount Rushmore player, had seven at the time as well. Someone was really going to top fourteen? On what planet?

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Beyond the match, the tournament and history, Sampras won something else that day: the affections of the public. For years he was admired, not adored. His career-long disdain for publicity came at a time when sports fans were beginning to seek more than mere excellence from their sports heroes. Here was Sampras, winning clinically but never revealing himself by letting down the drawbridge on his life. Even when he played, Sampras did so with his head down. (“I’m looking for coins,” he quipped, a nod to the sense of humor his confidantes have always sworn was part of Sampras’s personality.)

It didn’t help that Sampras’s factory setting of Southern California reserve was thrown into sharp relief by the charisma and energy of his great foil. All neon and frosted tips, Agassi arrived on the scene with all the subtlety of his hometown, Las Vegas. He talked trash and played to the crowd and married (and divorced) movie stars. Even when Agassi evolved into the sport’s wise man, his transformation—the interest in charter schools, the bracingly candid autobiography—still entailed being a public figure. As Agassi often put it, “Pete would never want my life. I would never want his life.”

It wasn’t that Sampras was boring, as it was often and unfairly shorthanded. It wasn’t that he was a jerk. And it certainly wasn’t that he was insecure. If anything, Martin puts it, Sampras had the self-assurance to commit himself to becoming the world’s best tennis player and decline to indulge in anything that wasn’t in service of that. “As uncomfortable as Pete would seem in public, I always got the sense he was as comfortable in his skin as anyone could be.”

That Sunday in New York Sampras was recast, finally, as the fan favorite. He was the underdog, the old guy trying to prove he still had the magic. The majority of the 25,000 fans inside Arthur Ashe Stadium rooted for him. (So did millions of casual sports fans, awaiting the start of the NFL season on CBS immediately after the match.) Sampras sensed this. In a complete lapse in character, he shouted during the match, “That’s what I’m talking about!” The crowd inside Ashe went nuts. When he finally won, he reckoned that he received the loudest ovation of his career.

Capitalizing on this story line, the chance finally to get Sampras his due, organizers lined up a Manhattan media tour for him. Morning shows, drive-time shows and late-night shows. Sampras, ever graciously, declined it all. He flew home to L.A., a contented man, a champion. He never played another professional match.

Starting in his early 30s—when so many of his peers in conventional lines of work were just entering their meaty years—Sampras was off the clock. And he was faithful to his retirement as, previously, he was to his work. After years of keeping a strict schedule, he let his days unspool in the most leisurely way. After years of displacement—threading the world, sleeping in an unending constellation of hotels, living out of bags—he would go months without leaving his sprawling home in Beverly Hills.

In the late 1990s, Sampras spotted Bridgette Wilson while out in Los Angeles, and asked a mutual friend for her number. They married in 2000, a fittingly small and private ceremony, though Elton John was the musical guest. Wilson was an ascending actress, but, to her credit, never felt fully comfortable in Hollywood. As he retired, she dialed back her career as well, and together, they began raising two boys, Christian, born in ’02, and Ryan, born in ’05.

Once he dropped his sons off at school, Sampras might play golf, often at Bel-Air Country Club, where he has been a longtime member. He might play cards with friends. With a tennis court in the backyard, he might pick up a racket as well. (Ryan, 15, is a junior tennis player of some distinction.) He and Bridgette might collect the kids and head to their weekend home near Palm Springs.

“Every time I see him, he seems totally happy,” says Paul Annacone, a Tennis Channel broadcaster and Sampras’s longtime coach, who remains a friend. “He has a really good perspective and view on being a dad and a husband, and he does whatever he wants to do.”

It’s also significant what Sampras hasn’t done in retirement. While his contemporary, Jim Courier, has established himself as one of tennis’s most perceptive analysts, Sampras has shown no interest in commentating. His sister, Stella, is the terrifically successful head women’s tennis coach at UCLA; her brother has shown little interest in coaching a pro player.

With roughly $50 million earned in prize money—and easily double that in Nike money, appearance fees and bonuses—Sampras doesn’t exactly have urgent financial pressure to launch a second career.

For all the stability in his personal life, his historic record has proven to be sadly fragile. Just a few months after Sampras won that supposedly unassailable 14th major, a talented Swiss star with a game not dissimilar to Sampras’s won Wimbledon for the first time. Two years after that, a swashbuckling Spaniard won the French Open for the first time. Three years after that, a steady Serb won the Australian Open for the first time.

At this writing, the three aforementioned players d/b/a the Big Three—Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, respectively—have won 20, 20 and 19 majors. And it’s important to provide the timestamp, because all three are still active, still winning, and by extension, still distancing themselves from Sampras’s mark. (What’s more, each of the Big Three has won the “career slam,” each of four majors, whereas Sampras never claimed the French, played on clay, his worst surface.)

Imagine you’re Sampras, at 31, and after chasing history for your career, you retire atop the mountain. You’re still in your 40s and not once, not twice, but three times other men have summited higher. There are greater sports tragedies, sure. But this is something akin to Michael Jordan—who also played for the last time in the early aughts—being suddenly absent from most GOAT conversations.

But just as he was during his career Sampras has been extraordinarily, even jarringly, gracious about recent history. He’s never gotten worked up about that which he could not change. In 2009, as Federer was poised to win his 15th major, Annacone went golfing with Sampras at Bel-Air, and wanted to see how his former charge was handling the assault of history.

‘“I said, ‘It’s getting close. What do you think?’ ” recalls Annacone.

“It’s pretty amazing!” Sampras replied.

“What do you mean?” pressed Annacone who, ironically, would go on to coach Federer.

“Well,” said Sampras, “I just know how hard it was for me. If anyone else can do it, that’s just too good. That’s amazing!”

Similarly, as Nadal and Djokovic passed Sampras by, he’s given them nothing but praise and respect—and none of it the grudging variety. Says Annacone: “He’s pretty good at checking his ego at the door … most of all I think he gets the emotional fuel that it takes to continually be in the final weekends of majors and generally come through. When he sees these three guys do it, he’s just genuinely tips his cap, like, ‘Well done, guys.’ ”

Just don’t ask him to anoint a single GOAT. “I feel like every decade there’s the guy. Certainly Roger has been the best player. Rafa is up there with him. Djokovic is pushing. So it’s really hard to say. I mean, there’s not one greatest player,” Sampras told me in 2015. He also takes pains not to discount the past. “For five years [Rod Laver] didn't play any majors when he was in his prime, so he could have had over 20 majors.”

Beyond that, Sampras is friendly with all three of the men who have passed him. He has known Federer the longest. They played each other once in pro competition, a memorable passing-the-baton match at Wimbledon in 2001. They have been bracketed together ever since.

A different kind of warmth passes between Sampras and Nadal. They may be separated by language, culture and a dominant hand, but they have found a kind of game-respects-game common ground. They also share an instinct for avoiding the trappings of stardom and would just as soon never leave their families or put on a collared shirt, much less a tux, if they didn’t have to.

Ironically, perhaps, Sampras is also close with Djokovic. The Serbian seeks to involve himself in politics and envisions himself (sometimes to his detriment) as a global figure, and is, unmistakably, more front-facing than Sampras ever was or wants to be. But they’ve bonded over the relentless pursuit of excellence and the joys of parenting two kids. Djokovic spends considerable time in Los Angeles, and has been known to visit Sampras when he does.

Hoping to rekindle memories of Sampras before they fade like an old photo, the longtime tennis writer Steve Flink recently wrote a book titled, fittingly, Pete Sampras: Greatness Revisited. Flink concludes: “He does not sound like he is feeling sorry for himself in the least, nor does he show any resentment towards Roger, Rafa, or Novak. It appears to me that it is quite the opposite; he is proud of what he did, and he still believes he could have competed favorably against anyone in history including Federer, Djokovic, and Nadal. But he also appreciates their greatness and the way all three have represented themselves. He gives them full marks for breaking his record at the Slams.”

In the course of his research, Flink spoke with Sampras about the operatic 2019 Wimbledon final in which Federer held match points but ultimately lost to Djokovic in a match that will have historical implications for decades. (Or so we think, anyway. Perhaps tennis history is not quite as durable as previously thought.) Sampras watched the match with his family and told Flink how wrenching he found it. “He could not stop thinking about it the rest of the day,” recalls Flink, “and his sentiments were twofold— great respect for Djokovic’s grit and determination and sympathy for Federer losing a heartbreaker.”

Like all athletes, Sampras gets asked the predictable question: Do you miss tennis? Sampras has a standard answer: “I miss the game, but I don’t miss the stress of it.” Part of the stress stemmed from the expectation he placed upon himself. Part of the stress also came from being a public figure. “Now,” says Martin, “in some ways he has the ultimate freedom. He doesn’t do anything he doesn’t want to.”

For almost two decades now, Sampras has led a quiet, private, homebound life that might bore some people, Agassi included. But to plenty of others—most important, of course, Sampras himself—it veers close to meeting the definition of charmed. He may no longer hold the all-time majors record. But he went out on top. He hasn’t budged much.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• We Could Sure Use Dick Cavett Right Now

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

0 Comments