The bad boy of bowling is finally hanging it up, but after four decades on tour, he’s still a kid at heart

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

In the bowling world, some say that the pins don’t care who you are, which is probably why Pete Weber always felt the need to stare them down the same way, every time, in an effort to remind them. He glared down the lane as if the pins’ very presence was denying him some function necessary for his ultimate happiness. Like they were untrained dogs and he was an impatient kettle owner holding a broken leash.

He celebrated their ultimate, tumbling demise by chopping his hands on either side of his crotch like the professional wrestlers he so admires. He barked back at hecklers. He would, at times, engage in turbulent trash talk with his own wife sitting in the stands behind him. He is evidence as to what happens when a 14-year-old makes up his mind about what he wants to do in life and how he wants to live it, cementing the whole thing in place, never once veering off course.

Standing five feet, seven inches tall, Weber has always been light enough to be toppled over by the artificial gusts coming from the ball return. His trademark look once included a bonnet of salt and pepper hair gelled and yanked back like an old crooner, though his dome is now buzzed. A mouth full of dental work always gleamed underneath the light from the studio television setup. Since the turn of the millenium, he’s worn sunglasses or one-piece viper baseball shades that would often get ripped off his head after a bum spare and shelved on his chair next to his post-match cigarettes. NFL Hall of Famer Terrell Owens, a huge fan of Weber’s, once donned the same pair as a tribute during a celebrity Pro-Am match the pair played together (they won).

During his final U.S. Open victory in 2012 in South Brunswick, N.J., the day he broke his father, bowling legend Dick Weber’s most prestigious record of Open championships won with arguably the greatest shot in the sport’s history (needing, and getting, a strike to win on the final shot, with the most challenging lane conditions of the year), he spent the entirety of the finals eyeing up a person he accused of moving during his approach and rooting against him.

A 12-year-old boy in the general vicinity of Weber’s glare was so scared he was the one doing something by accident that he ended up hiding behind the advertising signage on the side of the lane. Accounts of whether there actually was a heckler differ. Weber and some of his close friends say there was. Mike Fagan, his opponent in the finals, says that if you had to hook him up to a lie detector test today, he would guess there was not (Weber later signed a pin for the hiding boy, after the commissioner of professional bowling stopped by his seat to make sure he would accept it and that he wasn’t afraid).

“We were trying to figure it out,” legendary broadcaster Gary Thorne, who was on the call that day, says. “Was someone heckling him? We wanted to figure out who it was and we never found anyone.”

After winning that tournament, Weber, in a moment of pure adrenaline, pointed to the crowd and bellowed the words that would make him famous beyond the insular world of bowling. “Who do you think you are? I am!” He would later clarify that he meant to say, “Who do you think you are rooting against me? I am the man of this tournament.” Every year on the anniversary of that victory, the clip gets tens of millions of streams and retweets. The saying is plastered on T-shirts and coffee mugs, the royalties for which Weber doesn’t see a dime. Thorne does a round of radio interviews commemorating the occasion. Pete says, for a little while, his kids teased him about it. It may be the most visible moment in modern bowling history; the kind of viral injection of national attention that could keep the tour in the public consciousness.

But few have taken the time to appreciate the man behind the botched colloquialism. Before that moment and certainly after, Weber was typecast as the sport’s rambling Captain Jack Sparrow. He was encouraged by later generations of less stuffy, more viewer-oriented PBA ownership to act how he wanted to act.

Bowling was once the most popular televised sport in America, with a television deal on ABC that lasted from 1962 to ’97. They could fill arenas overseas. Weber, taking hold of its reins in the early 1980s, almost single handedly kept it alive through its leanest years, which included several fizzled television deals and changes in ownership. At a time when the sport lost the ability to sell itself, Weber placed a price tag on his rear end and pointed both thumbs directly at his face.

Earlier this year, at 57, Weber retired from the national tour, rolling his final frames as he noted the strength of the game’s young guns who can crash the pins much harder now with heavier balls and two-handed rolls (he still plans to be active in the senior tour, for bowlers over 50, and has already racked up several victories). His final moments on the National tour would seem, to the layperson, consistent with the Weber they knew through the keyhole of that singular, viral moment. He rolled a strike, picked up a spare, then hopped on live television a few hours later and dropped the f-bomb, which altered plans for him to act as a color analyst for the end of the tournament (“I wouldn’t [say f---] on live TV,” he told the commissioner afterward. “Pete, we were on live television,” the commissioner replied).

Those who know him, though, insist that Weber has been largely misunderstood. We don’t see the boy inside the bowler.

Sure, Weber artfully donned the role of the sport’s heel, vowing in private player meetings to keep viewers locked on the channel whenever he slid his fingers into a ball. Yes, there were stints in rehab and a pair of notable suspensions for tktk back when bowling fancied itself analogous to the sterile world of golf. But there is also the person who didn’t want to discuss his post-retirement interview or difficult past because, a work acquaintance said, it pained him to cuss like that publicly in retrospect. His dad would never have done that.

There was someone who offered the pins that same, respectful hatred; that same angry stare, roll after roll, nearly every day for the entirety of his life, long after cynicism and boredom might set in for the lot of us. And now, as he looks at life on the senior tour and, admittedly, more time away from the nacho cheese and light-beer-soaked carpets that have contained him throughout most of his sentient existence, bowling’s alleged bad boy is looking for his slice of the golden years; peace and calm both on the lanes and off, while his sport grapples with the absence of its greatest draw.

“I’ll spend a little more time at home I guess,” Weber says in his trademark smoky baritone. “Spend a little more time around the grandkids. I just found out I’m going to be a grandpa again. That’ll be neat. Watch them grow up. I’m just going to enjoy life right now.”

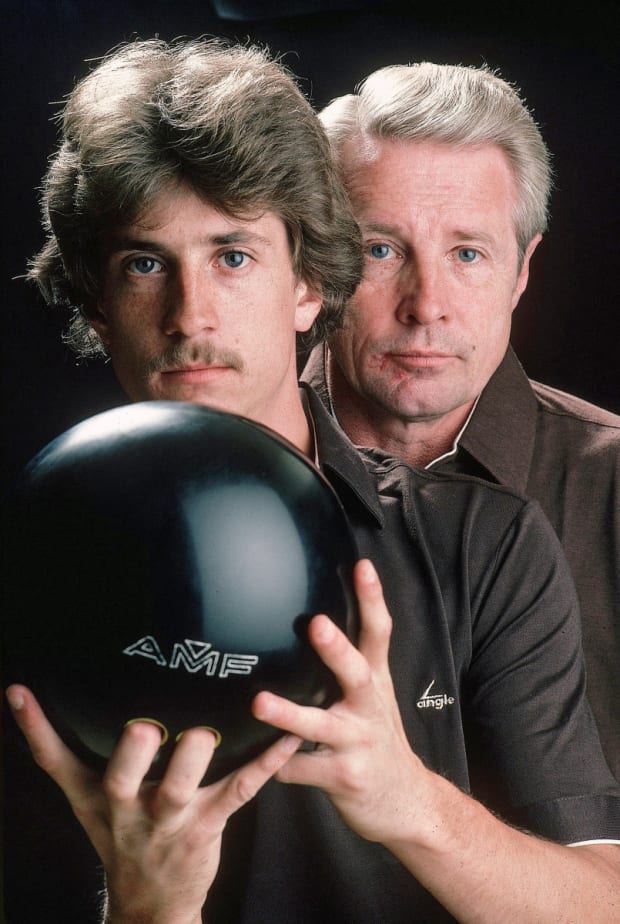

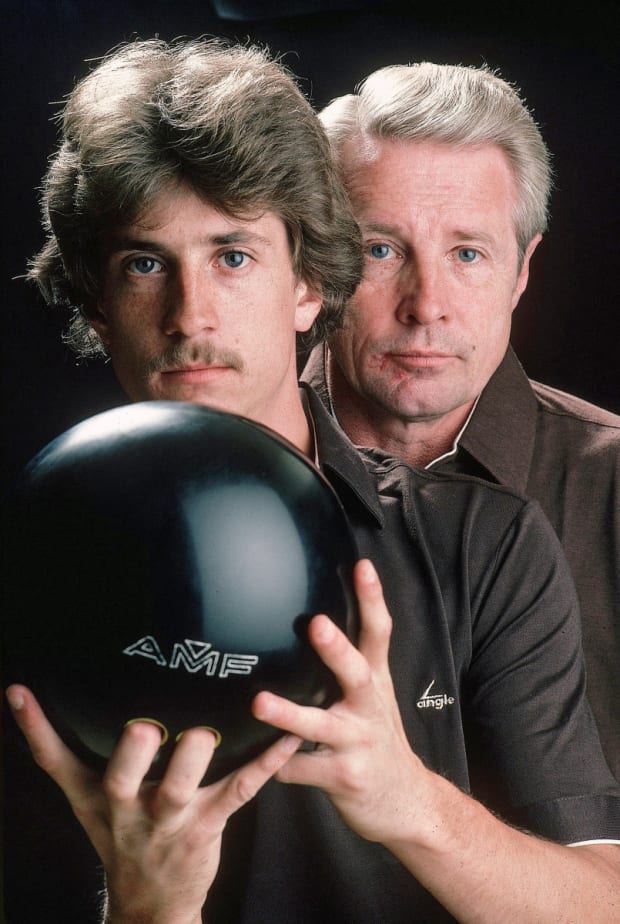

There is an image of Weber that endures beyond the ones that cycle through his greatest hits — the self high-fives, violent finger-pointing down the lane and John McEnroe-ian dialogue with both himself and anyone who crossed him during the course of a match. It was, as one spectator remembered, after a tournament in Syracuse, N.Y., when Weber was just starting out as a professional. Barely over 18. The crowds had scattered for the day. Bowling was still the most popular televised sport in America and Weber was a rising star, the son of Dick, bowling’s version of Jack Nickalus.

And there was Pete, just idling around. When the cameras packed up and went home, he was in the arcade playing pinball alone. Pete loves video games, the classics. He is, to this day, a Golden Tee aficionado and has watched professional wrestling religiously since the age of 12, having borrowed his famous crotch chop from the likes of Triple H, Shawn Michaels and the rest of D Generation X. A perpetual kid, miles away from home who may have grown up too fast or, in some ways, the best ways, never at all. It was a personality injection that helped wake the sport—and really, all major professional sports—to its eventual reality: interesting people make it work. Golf needed Tiger Woods’s fist pumping after rolling in long putts. Poker needed Phil Hellmuth’s bratty, meandering tableside conversations. Bowling needed Weber to figuratively elbow drop his opponents at the end of a big match.

He stays connected to his roots as an excitable, rubber-burning teenager bowling jackpots with visiting professionals growing up outside of St. Louis. Until Dick passed in February 2005, Pete would call him after every game and walk through the details of each shot as if they were still rolling together at Dick Weber lanes. That responsibility was then passed to his mom, Juanita, who died in April 2020.

Over 41 years, he’s won 37 titles (fourth all-time), reached 67 finals (third all-time) and made 152 top-fives (second all-time). He’s made more money than all but one bowler in PBA history. It would be difficult to find someone who wouldn’t place Weber among the most important figures in modern PBA history. He is the type of devotee who has, like a kid, never taken time to slow down for one moment, whirring at full speed in one direction so feverishly that he never once thought about what life might be like if he never picked up a bowling ball.

Pete dropped out of high school and joined the tour when he was 14, eschewing an idyllic childhood in the St. Louis suburbs for an adolescence, and a life, on tour. “I’ve never thought about anything but being a bowler,” he said.

“He’s got a very young mind still,” PBA commissioner Tom Clark says, referring to Weber’s unique internal concoction of innocence and explosiveness. “That young mind grew up in the 70s.”

And so there were some drugs. There was drinking. What were you at 18? What were any of us? How mature would we be on the road every weekend, hanging out with people twice our age, stuffing our pockets full of game checks from a popular, televised sport? Weber told the South Florida Sun Sentinel back in 1986 that he was spending $500 a week on cocaine. The year before, he told Sports Illustrated about bowling in the high 200s after a day spent downing full-strength long island ice teas. Bowling’s opinion of him has changed significantly since, taking a hard right turn from the unease some expressed publicly about him during the 1980s. Marshall Holman, viewed as bowling’s original bad boy, once told People magazine in 1988 that Weber was “a real embarrassment” to the tour. Today, he says: “We’ve both grown up a lot over the years. Pete’s always been a real gentleman when he hasn’t been partying to excess. I think I really grew to appreciate him as a player and a person back in the late 1990s when I was calling his games on television and I could appreciate what he did. When we stopped competing, it made it a lot easier for our friendship to grow.”

Fagan, who bemoaned Weber’s abuse of a fan—real or imagined—after Weber’s who do you think you are? I am moment at the U.S. Open, noted back in 2012 that Weber was alienating the fans they were struggling to attract. He says of Weber now: “He has been the most noteworthy person in the sport for 40 years. Sometimes good, sometimes bad. But he made bowling fun again.”

Underneath it all is a beautiful purity. A true love and joy consistent with the boy who’d entered the tour before he was eligible to vote. That’s what, friends say, doesn’t get talked about as much. Fellow bowling icon Norm Duke says he remembers riding around with Weber listening to REO Speedwagon. They would spend these long, sunny afternoons together golfing and getting lunch before a night match in places like Lake Havasu City, Ariz. In his head, Duke would be thinking “My God. I can’t believe I’m sitting here listening to Speedwagon, going golfing and getting lunch with Pete Freakin’ Weber. Can it get any better than this?”

Then, suddenly, Weber would express the same thought out loud, as though the two of them were connected on this hidden wavelength.

“Well man, this is a really good day for me,” Weber would say. “I’m sitting here having lunch with Norm Duke!”

“There are a number of sides to Pete Weber, but the one side that is most consistent is his loyalty and his friendship. That doesn’t waiver, ever,” Duke says. “To be as brash as he is, the guy is so humble.”

He added: “Neither one of us went to college. Our college was the PBA tour. We went through times. They’re not all so pretty. You’re learning life’s lessons on the road by yourself. We were kids. All we’ve ever known was the road and what it will teach you.”

Duke learned one of those lessons, about both Pete and life, in St. Louis back in 1993 at a Blues hockey game. Duke and Weber got connected to the intermission show through a wealthy friend and there they were at center ice in front of a packed house. Duke was responsible for one half of the arena and Weber the other. Both had three pucks from center ice. The one who made the most shots won their section a free taco value meal. Duke made his approach with all the ferocity of a baby bird, sliding the puck into the back of the net as if it were a curling stone. He got booed.

Then comes Weber, already revving up the crowd in America’s bowling capital, the place of his birth. There is no consciousness or thought behind it. Just a long windup and full-strength rip, blasting the puck over the crossbar. The crowd goes wild.

Duke, determined to win the crowd over with a victory, slides another puck in at a snail’s pace to more boos and again Weber misses the net with a comically powerful swing.

“Half of the field gets a free taco basket, and they’re booing the man who gave it to ’em,” Duke says, laughing.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Then, on his last shot, Weber connected. Dead center. Back of the net. Lights flashing. Music blaring. He’s soaking up the energy and feeding it back at twice the wattage. No one seems to care that he cost them a meal. Duke, trying not to be outdone, tried to match him with a mammoth slap shot and missed. Maybe, he thought, they’d respect the effort. Maybe they just didn’t appreciate the kiddie shots.

He’s booed off the ice. Still, he says, the loudest jeers he’s ever heard in his life.

“I’ve often said, Pete can reach out through a television, grab you by the neck, turn your head toward him and say ‘Oh no, no, no. You might want to watch this,’ ” Duke says. “And people do. And it speaks to his entertainment value.”

That was—and still is—Pete. At some point along the way the boy made an agreement to stay young at heart. To keep wrestling on the TV and keep crotch chopping when the action got hot and the network cameras were on. To keep playing Golden Tee. To linger in the arcade. At some point, the rest of the world—and especially professional bowling—realized something powerful. His aliveness, whether it be in the body of a boy or a man in his late fifties, was infectious. It was sellable.

It is a disposition that Weber is thoroughly proud of. His success as a draw is not anecdotal. Clark says that, under no uncertain terms, when Weber was on, the ratings went up. Clark still finds himself reflexively checking his phone when Weber is in the money at a senior tour event.

“I never planned this stuff out; it just happens,” Weber says. “I never looked in the mirror and practiced my crotch chop. If people don’t like it, I’m sorry. That’s just me being me.

“If they like it, they cheer me on. They say Come On PDW, let’s go! And if they don’t, people don’t really say too much at the TV. show or when I’m doing it. But they’ll get on social media or whatever and say ‘What an ass.’ But I don’t care. You can think what you want. Because people that really know me, they love me.”

Duke says that Weber’s most important trait was not that he put bowling on the map, but that he built new roads. After his performance there, Weber did talk show appearances, like ESPN’s SportsNation variety show. His strike and subsequent monologue was a mainstay on SportsCenter’s Top 10 plays. He wonders what will happen to those roads now.

“What are fans going to do without Pete?” Duke said. “What are we going to do without Pete?”

After wrapping up his final frame on the national tour, Weber was outside the bowling center leaning on a railing, smoking a cigarette. On the red painted walls behind him were the same thin, Big Lebowski–style neon stars that adorned every cursive bowling alley sign in America, most of which Weber has been inside at one point or another. All at once he looked deflated and relieved, having told the PBA’s digital reporter a few minutes earlier that he felt like his parents had been looking down on him from heaven approvingly. That it was time to hang it up.

Something happened along the way that he couldn’t shake. He would watch his ball hook at the desired pivot point on the lane and roll into the pins with the velocity of a go-kart crash. He would watch the real kids on either side, the young bowlers who work with heavier balls and whip the thing two-handed in order to increase torque and velocity. It was like, Weber said, “an atomic bomb” going off. Pins were splattering everywhere like soup from an uncapped blender.

That kind of bowling wasn’t fun anymore. At least not like this. He was spending more of his time being frustrated about the pins. About how they didn’t seem to care who he was anymore.

“When I’m outside the bowling center, I don’t have to think about that,” Weber said. “It’s like, hey, what am I going to have for dinner? Where am I going to play golf?”

He says the senior tour is a comfortable place. He bowls with his friends. He still rolls in a local league with his buddy in the neighborhood. Weber was alive back when the balls could only be made of rubber or plastic. He says “What we do now, when you can miss two arrows to the right and still strike, that’s not bowling. It’s fun, but they need to make the lanes a little tougher. Make spares come back into play.”

His brother, John, who is the regional and senior tour director of the PBA, says Pete’s retirement was surreal and emotional for a time; a moment that forced them to “look at a part of our lives passing away.” He’s not the only one. Bowlers who competed with him for a long time noted that Weber’s bowling mortality reminded them of their own. If Pete can’t do this forever, who can?

“I think he’s at peace now,” John says. “I do. He’s mellowed out a bit. He’s at peace with himself.”

As for what else life has to offer, Weber says he’s not sure. For now, it’s an enjoyable loop of bowling, golfing and dining in no particular order.

“As far as picking up anything? I really don’t know,” he says. “When I go out on the senior tour, I’m not going to get frustrated when I go out there, when I was bowling with the kids. I was hitting the pocket as much as they did but my ball wasn’t striking the way theirs did. I’ll have more success. I’ll be able to strike and hit and win again.”

But there are also the grandkids, the oldest of which is 11. Weber says he “loves being a grandpa, and if any other parent don’t say this they’re lying. If they don’t treat their grandkids 10 times better than they treated their own kids, they’re lying. I treat my grandkids 10 times better than I treated my own kids.”

He laughs, and talks about their outings together. Putt-putt golf, trips to the batting cages and games of wiffle ball and kickball in the backyard. One of his kids has a pool and he’ll head over, jumping in and throwing the little ones around.

If nothing else, it seems like the perfect place to land for a kid that refused to grow old.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• Micah Johnson Turns Baseball Stumble Into Crypto Dreams

The bad boy of bowling is finally hanging it up, but after four decades on tour, he’s still a kid at heart

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

In the bowling world, some say that the pins don’t care who you are, which is probably why Pete Weber always felt the need to stare them down the same way, every time, in an effort to remind them. He glared down the lane as if the pins’ very presence was denying him some function necessary for his ultimate happiness. Like they were untrained dogs and he was an impatient kettle owner holding a broken leash.

He celebrated their ultimate, tumbling demise by chopping his hands on either side of his crotch like the professional wrestlers he so admires. He barked back at hecklers. He would, at times, engage in turbulent trash talk with his own wife sitting in the stands behind him. He is evidence as to what happens when a 14-year-old makes up his mind about what he wants to do in life and how he wants to live it, cementing the whole thing in place, never once veering off course.

Standing five feet, seven inches tall, Weber has always been light enough to be toppled over by the artificial gusts coming from the ball return. His trademark look once included a bonnet of salt and pepper hair gelled and yanked back like an old crooner, though his dome is now buzzed. A mouth full of dental work always gleamed underneath the light from the studio television setup. Since the turn of the millenium, he’s worn sunglasses or one-piece viper baseball shades that would often get ripped off his head after a bum spare and shelved on his chair next to his post-match cigarettes. NFL Hall of Famer Terrell Owens, a huge fan of Weber’s, once donned the same pair as a tribute during a celebrity Pro-Am match the pair played together (they won).

During his final U.S. Open victory in 2012 in South Brunswick, N.J., the day he broke his father, bowling legend Dick Weber’s most prestigious record of Open championships won with arguably the greatest shot in the sport’s history (needing, and getting, a strike to win on the final shot, with the most challenging lane conditions of the year), he spent the entirety of the finals eyeing up a person he accused of moving during his approach and rooting against him.

A 12-year-old boy in the general vicinity of Weber’s glare was so scared he was the one doing something by accident that he ended up hiding behind the advertising signage on the side of the lane. Accounts of whether there actually was a heckler differ. Weber and some of his close friends say there was. Mike Fagan, his opponent in the finals, says that if you had to hook him up to a lie detector test today, he would guess there was not (Weber later signed a pin for the hiding boy, after the commissioner of professional bowling stopped by his seat to make sure he would accept it and that he wasn’t afraid).

“We were trying to figure it out,” legendary broadcaster Gary Thorne, who was on the call that day, says. “Was someone heckling him? We wanted to figure out who it was and we never found anyone.”

After winning that tournament, Weber, in a moment of pure adrenaline, pointed to the crowd and bellowed the words that would make him famous beyond the insular world of bowling. “Who do you think you are? I am!” He would later clarify that he meant to say, “Who do you think you are rooting against me? I am the man of this tournament.” Every year on the anniversary of that victory, the clip gets tens of millions of streams and retweets. The saying is plastered on T-shirts and coffee mugs, the royalties for which Weber doesn’t see a dime. Thorne does a round of radio interviews commemorating the occasion. Pete says, for a little while, his kids teased him about it. It may be the most visible moment in modern bowling history; the kind of viral injection of national attention that could keep the tour in the public consciousness.

But few have taken the time to appreciate the man behind the botched colloquialism. Before that moment and certainly after, Weber was typecast as the sport’s rambling Captain Jack Sparrow. He was encouraged by later generations of less stuffy, more viewer-oriented PBA ownership to act how he wanted to act.

Bowling was once the most popular televised sport in America, with a television deal on ABC that lasted from 1962 to ’97. They could fill arenas overseas. Weber, taking hold of its reins in the early 1980s, almost single handedly kept it alive through its leanest years, which included several fizzled television deals and changes in ownership. At a time when the sport lost the ability to sell itself, Weber placed a price tag on his rear end and pointed both thumbs directly at his face.

Earlier this year, at 57, Weber retired from the national tour, rolling his final frames as he noted the strength of the game’s young guns who can crash the pins much harder now with heavier balls and two-handed rolls (he still plans to be active in the senior tour, for bowlers over 50, and has already racked up several victories). His final moments on the National tour would seem, to the layperson, consistent with the Weber they knew through the keyhole of that singular, viral moment. He rolled a strike, picked up a spare, then hopped on live television a few hours later and dropped the f-bomb, which altered plans for him to act as a color analyst for the end of the tournament (“I wouldn’t [say f---] on live TV,” he told the commissioner afterward. “Pete, we were on live television,” the commissioner replied).

Those who know him, though, insist that Weber has been largely misunderstood. We don’t see the boy inside the bowler.

Sure, Weber artfully donned the role of the sport’s heel, vowing in private player meetings to keep viewers locked on the channel whenever he slid his fingers into a ball. Yes, there were stints in rehab and a pair of notable suspensions for tktk back when bowling fancied itself analogous to the sterile world of golf. But there is also the person who didn’t want to discuss his post-retirement interview or difficult past because, a work acquaintance said, it pained him to cuss like that publicly in retrospect. His dad would never have done that.

There was someone who offered the pins that same, respectful hatred; that same angry stare, roll after roll, nearly every day for the entirety of his life, long after cynicism and boredom might set in for the lot of us. And now, as he looks at life on the senior tour and, admittedly, more time away from the nacho cheese and light-beer-soaked carpets that have contained him throughout most of his sentient existence, bowling’s alleged bad boy is looking for his slice of the golden years; peace and calm both on the lanes and off, while his sport grapples with the absence of its greatest draw.

“I’ll spend a little more time at home I guess,” Weber says in his trademark smoky baritone. “Spend a little more time around the grandkids. I just found out I’m going to be a grandpa again. That’ll be neat. Watch them grow up. I’m just going to enjoy life right now.”

There is an image of Weber that endures beyond the ones that cycle through his greatest hits — the self high-fives, violent finger-pointing down the lane and John McEnroe-ian dialogue with both himself and anyone who crossed him during the course of a match. It was, as one spectator remembered, after a tournament in Syracuse, N.Y., when Weber was just starting out as a professional. Barely over 18. The crowds had scattered for the day. Bowling was still the most popular televised sport in America and Weber was a rising star, the son of Dick, bowling’s version of Jack Nickalus.

And there was Pete, just idling around. When the cameras packed up and went home, he was in the arcade playing pinball alone. Pete loves video games, the classics. He is, to this day, a Golden Tee aficionado and has watched professional wrestling religiously since the age of 12, having borrowed his famous crotch chop from the likes of Triple H, Shawn Michaels and the rest of D Generation X. A perpetual kid, miles away from home who may have grown up too fast or, in some ways, the best ways, never at all. It was a personality injection that helped wake the sport—and really, all major professional sports—to its eventual reality: interesting people make it work. Golf needed Tiger Woods’s fist pumping after rolling in long putts. Poker needed Phil Hellmuth’s bratty, meandering tableside conversations. Bowling needed Weber to figuratively elbow drop his opponents at the end of a big match.

He stays connected to his roots as an excitable, rubber-burning teenager bowling jackpots with visiting professionals growing up outside of St. Louis. Until Dick passed in February 2005, Pete would call him after every game and walk through the details of each shot as if they were still rolling together at Dick Weber lanes. That responsibility was then passed to his mom, Juanita, who died in April 2020.

Over 41 years, he’s won 37 titles (fourth all-time), reached 67 finals (third all-time) and made 152 top-fives (second all-time). He’s made more money than all but one bowler in PBA history. It would be difficult to find someone who wouldn’t place Weber among the most important figures in modern PBA history. He is the type of devotee who has, like a kid, never taken time to slow down for one moment, whirring at full speed in one direction so feverishly that he never once thought about what life might be like if he never picked up a bowling ball.

Pete dropped out of high school and joined the tour when he was 14, eschewing an idyllic childhood in the St. Louis suburbs for an adolescence, and a life, on tour. “I’ve never thought about anything but being a bowler,” he said.

“He’s got a very young mind still,” PBA commissioner Tom Clark says, referring to Weber’s unique internal concoction of innocence and explosiveness. “That young mind grew up in the 70s.”

And so there were some drugs. There was drinking. What were you at 18? What were any of us? How mature would we be on the road every weekend, hanging out with people twice our age, stuffing our pockets full of game checks from a popular, televised sport? Weber told the South Florida Sun Sentinel back in 1986 that he was spending $500 a week on cocaine. The year before, he told Sports Illustrated about bowling in the high 200s after a day spent downing full-strength long island ice teas. Bowling’s opinion of him has changed significantly since, taking a hard right turn from the unease some expressed publicly about him during the 1980s. Marshall Holman, viewed as bowling’s original bad boy, once told People magazine in 1988 that Weber was “a real embarrassment” to the tour. Today, he says: “We’ve both grown up a lot over the years. Pete’s always been a real gentleman when he hasn’t been partying to excess. I think I really grew to appreciate him as a player and a person back in the late 1990s when I was calling his games on television and I could appreciate what he did. When we stopped competing, it made it a lot easier for our friendship to grow.”

Fagan, who bemoaned Weber’s abuse of a fan—real or imagined—after Weber’s who do you think you are? I am moment at the U.S. Open, noted back in 2012 that Weber was alienating the fans they were struggling to attract. He says of Weber now: “He has been the most noteworthy person in the sport for 40 years. Sometimes good, sometimes bad. But he made bowling fun again.”

Underneath it all is a beautiful purity. A true love and joy consistent with the boy who’d entered the tour before he was eligible to vote. That’s what, friends say, doesn’t get talked about as much. Fellow bowling icon Norm Duke says he remembers riding around with Weber listening to REO Speedwagon. They would spend these long, sunny afternoons together golfing and getting lunch before a night match in places like Lake Havasu City, Ariz. In his head, Duke would be thinking “My God. I can’t believe I’m sitting here listening to Speedwagon, going golfing and getting lunch with Pete Freakin’ Weber. Can it get any better than this?”

Then, suddenly, Weber would express the same thought out loud, as though the two of them were connected on this hidden wavelength.

“Well man, this is a really good day for me,” Weber would say. “I’m sitting here having lunch with Norm Duke!”

“There are a number of sides to Pete Weber, but the one side that is most consistent is his loyalty and his friendship. That doesn’t waiver, ever,” Duke says. “To be as brash as he is, the guy is so humble.”

He added: “Neither one of us went to college. Our college was the PBA tour. We went through times. They’re not all so pretty. You’re learning life’s lessons on the road by yourself. We were kids. All we’ve ever known was the road and what it will teach you.”

Duke learned one of those lessons, about both Pete and life, in St. Louis back in 1993 at a Blues hockey game. Duke and Weber got connected to the intermission show through a wealthy friend and there they were at center ice in front of a packed house. Duke was responsible for one half of the arena and Weber the other. Both had three pucks from center ice. The one who made the most shots won their section a free taco value meal. Duke made his approach with all the ferocity of a baby bird, sliding the puck into the back of the net as if it were a curling stone. He got booed.

Then comes Weber, already revving up the crowd in America’s bowling capital, the place of his birth. There is no consciousness or thought behind it. Just a long windup and full-strength rip, blasting the puck over the crossbar. The crowd goes wild.

Duke, determined to win the crowd over with a victory, slides another puck in at a snail’s pace to more boos and again Weber misses the net with a comically powerful swing.

“Half of the field gets a free taco basket, and they’re booing the man who gave it to ’em,” Duke says, laughing.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Then, on his last shot, Weber connected. Dead center. Back of the net. Lights flashing. Music blaring. He’s soaking up the energy and feeding it back at twice the wattage. No one seems to care that he cost them a meal. Duke, trying not to be outdone, tried to match him with a mammoth slap shot and missed. Maybe, he thought, they’d respect the effort. Maybe they just didn’t appreciate the kiddie shots.

He’s booed off the ice. Still, he says, the loudest jeers he’s ever heard in his life.

“I’ve often said, Pete can reach out through a television, grab you by the neck, turn your head toward him and say ‘Oh no, no, no. You might want to watch this,’ ” Duke says. “And people do. And it speaks to his entertainment value.”

That was—and still is—Pete. At some point along the way the boy made an agreement to stay young at heart. To keep wrestling on the TV and keep crotch chopping when the action got hot and the network cameras were on. To keep playing Golden Tee. To linger in the arcade. At some point, the rest of the world—and especially professional bowling—realized something powerful. His aliveness, whether it be in the body of a boy or a man in his late fifties, was infectious. It was sellable.

It is a disposition that Weber is thoroughly proud of. His success as a draw is not anecdotal. Clark says that, under no uncertain terms, when Weber was on, the ratings went up. Clark still finds himself reflexively checking his phone when Weber is in the money at a senior tour event.

“I never planned this stuff out; it just happens,” Weber says. “I never looked in the mirror and practiced my crotch chop. If people don’t like it, I’m sorry. That’s just me being me.

“If they like it, they cheer me on. They say Come On PDW, let’s go! And if they don’t, people don’t really say too much at the TV. show or when I’m doing it. But they’ll get on social media or whatever and say ‘What an ass.’ But I don’t care. You can think what you want. Because people that really know me, they love me.”

Duke says that Weber’s most important trait was not that he put bowling on the map, but that he built new roads. After his performance there, Weber did talk show appearances, like ESPN’s SportsNation variety show. His strike and subsequent monologue was a mainstay on SportsCenter’s Top 10 plays. He wonders what will happen to those roads now.

“What are fans going to do without Pete?” Duke said. “What are we going to do without Pete?”

After wrapping up his final frame on the national tour, Weber was outside the bowling center leaning on a railing, smoking a cigarette. On the red painted walls behind him were the same thin, Big Lebowski–style neon stars that adorned every cursive bowling alley sign in America, most of which Weber has been inside at one point or another. All at once he looked deflated and relieved, having told the PBA’s digital reporter a few minutes earlier that he felt like his parents had been looking down on him from heaven approvingly. That it was time to hang it up.

Something happened along the way that he couldn’t shake. He would watch his ball hook at the desired pivot point on the lane and roll into the pins with the velocity of a go-kart crash. He would watch the real kids on either side, the young bowlers who work with heavier balls and whip the thing two-handed in order to increase torque and velocity. It was like, Weber said, “an atomic bomb” going off. Pins were splattering everywhere like soup from an uncapped blender.

That kind of bowling wasn’t fun anymore. At least not like this. He was spending more of his time being frustrated about the pins. About how they didn’t seem to care who he was anymore.

“When I’m outside the bowling center, I don’t have to think about that,” Weber said. “It’s like, hey, what am I going to have for dinner? Where am I going to play golf?”

He says the senior tour is a comfortable place. He bowls with his friends. He still rolls in a local league with his buddy in the neighborhood. Weber was alive back when the balls could only be made of rubber or plastic. He says “What we do now, when you can miss two arrows to the right and still strike, that’s not bowling. It’s fun, but they need to make the lanes a little tougher. Make spares come back into play.”

His brother, John, who is the regional and senior tour director of the PBA, says Pete’s retirement was surreal and emotional for a time; a moment that forced them to “look at a part of our lives passing away.” He’s not the only one. Bowlers who competed with him for a long time noted that Weber’s bowling mortality reminded them of their own. If Pete can’t do this forever, who can?

“I think he’s at peace now,” John says. “I do. He’s mellowed out a bit. He’s at peace with himself.”

As for what else life has to offer, Weber says he’s not sure. For now, it’s an enjoyable loop of bowling, golfing and dining in no particular order.

“As far as picking up anything? I really don’t know,” he says. “When I go out on the senior tour, I’m not going to get frustrated when I go out there, when I was bowling with the kids. I was hitting the pocket as much as they did but my ball wasn’t striking the way theirs did. I’ll have more success. I’ll be able to strike and hit and win again.”

But there are also the grandkids, the oldest of which is 11. Weber says he “loves being a grandpa, and if any other parent don’t say this they’re lying. If they don’t treat their grandkids 10 times better than they treated their own kids, they’re lying. I treat my grandkids 10 times better than I treated my own kids.”

He laughs, and talks about their outings together. Putt-putt golf, trips to the batting cages and games of wiffle ball and kickball in the backyard. One of his kids has a pool and he’ll head over, jumping in and throwing the little ones around.

If nothing else, it seems like the perfect place to land for a kid that refused to grow old.

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• How Ricky Williams Found Himself in the Planets and the Stars

• Micah Johnson Turns Baseball Stumble Into Crypto Dreams

0 Comments