From a heroic preseason moment to a shaved head to ‘Tecmo Bowl’-inspired tantrums, remembering a fourth-string quarterback in Foxboro.

As the fourth-string quarterback took the field, a fresh rookie buzz cut beneath his silver helmet, his teammates on the visiting sidelines prayed that he would put an end to their misery. The Silverdome had become a stadium-sized sauna on an August night in Pontiac, Mich., later described by one sweat-soaked reporter as “hot, humid, and air-conditioning-less.” The Patriots and Lions were tied at 10, and with less than a minute on the game clock every NFL veteran’s nightmare loomed: preseason overtime.

For Tom Brady, it was a dream chance to impress. The ball was spotted at the New England 31 after a Lions punt. Two modest gains brought the Pats closer to but not across midfield, each tick of the clock making a delayed flight home more likely. Just when the team’s fate seemed certain, though, Brady reared back and hit receiver Sean Morey between the safeties, a 47-yard connection. Adam Vinatieri came on to make a chip shot field goal on the next play, hitting the netting with two seconds left, guaranteeing an escape from the Detroit suburbs.

Celebratory high-fives and back slaps awaited as Brady left the field, according to the Boston Globe. So did a gesture of gratitude from one teammate hip to the latest in portable technology.

“Those guys did not want to keep playing,"

Brady told the Globe. “One of the guys let me use his DVD player because he said, ‘At least you didn't keep me around for another half-hour.’ So that was nice.”

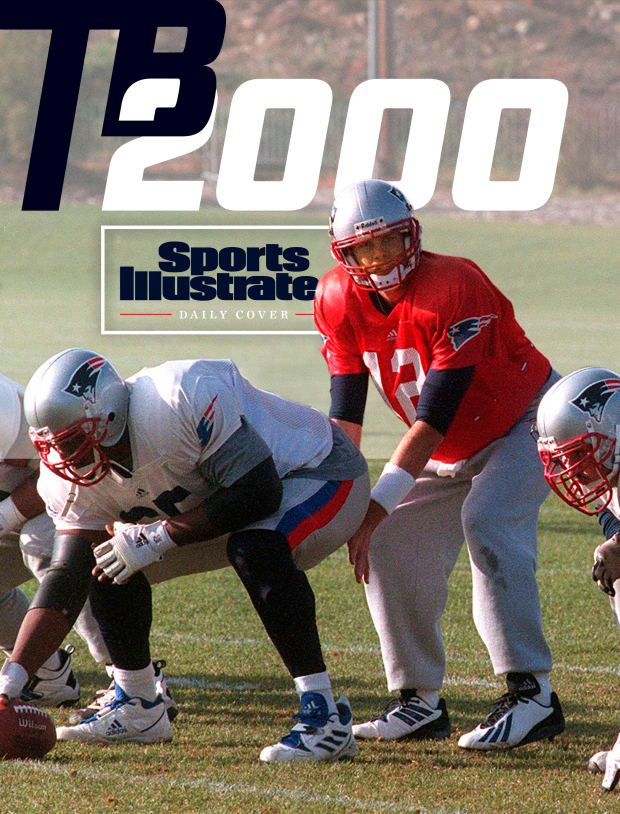

Bill Greene/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

When it comes to all that Brady has done in the two-plus decades since that night—his first extended NFL action after previously making a small cameo in the Patriots’ preseason opener against his childhood-favorite Niners—hindsight is 20/20. (Devotees of his pricey performance supplements and “recovery pajamas” might prefer TB12/TB12.) Now 44, he is the NFL’s only quadragenarian heading into the 2021 season, the latest in a career so absurdly long that all but 16 of his current teammates on the Buccaneers’ 80-man roster are as close in age, or closer, to Brady’s 14-year-old son Jack (who has been tagging along with Pops to practice as a guest ball boy at Tampa Bay’s training camp this summer) than they are to their quarterback.

Ten Super Bowl appearances and seven increasingly bejeweled rings later, the usual Brady narrative picks up in 2001 when he takes over for Drew Bledsoe and tucks the Lombardi Trophy, among other things, under his arm; the 2000 season is a forgotten footnote in his arc. And for good reason: Aside from his game-winning drive in Detroit, Brady did next to nothing else memorable on the field as a rookie, squeaking onto the active roster when coach Bill Belichick made the unusual decision to keep four quarterbacks. While Brady finished the season as Drew Bledsoe’s backup, he completed a single 6-yard pass in his lone regular-season appearance—Week 13 mop-up duty during a lopsided loss in, coincidentally, the Silverdome.

Even his crowning moment, the dart to Morey, is mostly lost to history; requests for surviving footage to the Lions, the Patriots and NFL Films turned up empty, while Brady “really didn’t have much recollection” of the 13–10 victory, according to a Bucs spokesperson.

But bits of that memory—of Brady’s first NFL heroics—linger for some former teammates. Among them is Eric Bjornson, a tight end who was watching from the sidelines when Brady hit Morey up the seam. “It just seemed like such a mature throw for a kid in his first year,” Bjornson says. “Late-game like that, guys usually don’t take a ton of risk … He fired that thing right down the throat of the defense. Five-step drop, no shuffle, no nothing, just … BANG! Like you’ve seen him do a thousand times, but this was the first sign of how calm, cool and confident he was that we were going to win.”

As it was happening, Bjornson had no reason to believe Brady’s throw would signal anything of note, save for a chance for the rookie who played college ball in nearby Ann Arbor—a sixth-rounder and the seventh draft pick of the Belichick era then buried on the depth chart behind Bledsoe, Michael Bishop and John Friesz—to bank some quality NFL game film. “I don’t remember much, but I remember being happy that this would open up a door for him to land somewhere else,” Bjornson says. “I didn’t think in 8 million years that he’d make the team.”

Two-plus decades later, it is perhaps a measure of Brady’s status that Bjornson and other members of the 2000 Patriots—all of them having long since retired from football and moved on to other lines of employment (Bjornson works in employee benefits consulting)—can recall anything at all about his rookie season. But they do. Like how he handled the task of performing skits during training camp. “One night, Tom was just up there doing stand-up, telling jokes,” Bjornson says. “It was pretty damn funny.” And how he looked with that shaved head. “Completely ridiculous,” Chris Eitzmann, also a tight end on that 2000 team, says

And his relative lack of fame, even among locals. “He’d be trying to talk to girls at the bars and they wouldn’t give him the time of day, and we’d all be laughing about it,” says defensive lineman David Nugent, who roomed with Brady for three years starting that preseason. “Obviously, that changed.”

Above all else, they remember the obsessive work ethic Brady brought every day, beginning when the rookie would pull his yellow Jeep Wrangler—“ugly and bright,” as Eitzmann describes the gift Brady received from an area car dealership upon making the team—into the parking lot before sunrise.

It was the same approach Brady summarized to the Globe that preseason, the week after the Detroit game: “I am going out there every day, trying to get better and see how good I can possibly be because there are a lot of great quarterbacks here,” he said. “It is so competitive that you just have to go out and worry about yourself, worry about completing balls when you are in, and hopefully get better each day.

“Then, hopefully, the coach sees something he can work with and then you are able to get your shot.”

Lonie Paxton was an undrafted long snapper from Sacramento State in 2000, thrilled to simply score an invitation to an NFL rookie camp, when he first met Brady on their shared connecting flight to New England. “I got a T-shirt and a plane ticket, so I was going to prove myself,” Paxton says. “I was not really expecting too much.” He quickly learned that his new traveling companion, the 199th pick that year, had similar plans. “He’s always had that chip on his shoulder,” Paxton says of Brady.

Eitzmann realized this soon after workouts started at Rhode Island’s Bryant University, by which point he and Brady had begun a tradition of staying late after practice to throw and run routes. “We’d go until I was completely gassed and couldn’t anymore,” Eitzmann says. One day, “We were walking off, and he was like, ‘Know what Eitz, I’m gonna beat out Bledsoe.’ Which at the time just sounded like the most preposterous thing ever. Bledsoe was a god in New England, and here’s this skinny kid.”

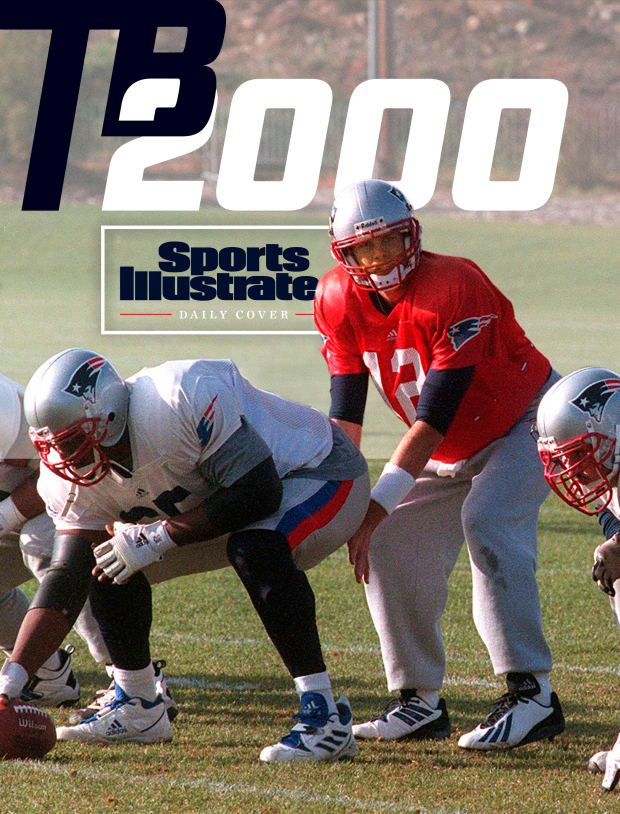

Carlos Osorio/AP Photo

Absent any meaningful reps to prove himself, Brady did whatever he could to get ahead. “He’d always be out there throwing, running ... everything,” receiver Shockmain Davis says. Bjornson remembers his preseason roommate, Friesz, coming home to gush about the meticulously detailed “works of art” that Brady would draw in the quarterback room when quizzed by a coach. Others recall him staying up to study the playbook in his temporary lodging at the End Zone Motel in Foxboro, Mass., tuning out the live concerts the divey establishment hosted on weekends. “His drive to get better was insane,” Eitzmann says. “He’s probably the most competitive person I’ve ever met.”

The football field wasn’t Brady’s only arena here. “Nintendo, Ping-Pong, pool, you beat him and he was pissed,” Eitzmann says. Later that year, when Brady was living with Eitzmann and Nugent in a condo he bought from cornerback Ty Law, the trio regularly staged double-elimination tournaments in Tecmo Super Bowl. A Bay Area native, Brady would play as the Niners, while Eitzmann often elected for the Raiders, featuring an unbeatable Bo Jackson. “He’d throw the controller against the wall,” Eitzmann says. “He wouldn’t talk to me for half a day.”

Despite his best efforts Brady remained a glorified practice squad player most of that season, taking snaps sparingly and staying home for away games. But it was clear that he had caught the attention of veteran peers, if only judging by Bledsoe's pranks targeting the yellow Jeep. “At one point he filled it with packing peanuts; at one point there was flour in the vents,” Eitzmann says. All the while, Brady’s intensity never waned. “Every night, he would go down to our basement and watch film, preparing like he was the starting quarterback,” Nugent says. “Then I wouldn’t see him in the morning, because he’d get up so early and go to the stadium and watch film before anyone else got there.”

One night, after returning from a road trip, Nugent checked in to see how Brady, no stranger to quarterback competition due to his time at Michigan, was handling the lack of action. “I asked him, ‘You hanging in there?’ ” Nugent recalls. “He was so competitive, but so far down the depth chart. He said, ‘You know, I can’t control how much practice time I get, or how the guys in front of me play. All I can control is how much I study, what I do with the one or two reps they give me. And when my time comes, I’ll be ready.”

Pats fans everywhere can recite what happened next by rote: Bledsoe went down in Week 2 of the 2001 season, sustaining severe internal injuries on a hit that hastened his exit from New England; Brady stepped up and soon became the youngest Super Bowl–winning quarterback ever, assuming the unfamiliar role of local deity, much to his—and everyone else’s—surprise “I’ve got all sorts of stories about him getting standing ovations at Outback Steakhouse, getting recognized as we were heading into the playoffs,” Nugent says. “At the time it was brand-new to him. We’d get back in the car and he’d be freaking out.”

• In the Shadow of Tom Brady: What It Means to Be Pick 199

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

• How the Bucs Are Leading a Linebacker Revival

• Magnificent Seventh: How Brady’s Bucs Became Super Bowl Champions

From a heroic preseason moment to a shaved head to ‘Tecmo Bowl’-inspired tantrums, remembering a fourth-string quarterback in Foxboro.

As the fourth-string quarterback took the field, a fresh rookie buzz cut beneath his silver helmet, his teammates on the visiting sidelines prayed that he would put an end to their misery. The Silverdome had become a stadium-sized sauna on an August night in Pontiac, Mich., later described by one sweat-soaked reporter as “hot, humid, and air-conditioning-less.” The Patriots and Lions were tied at 10, and with less than a minute on the game clock every NFL veteran’s nightmare loomed: preseason overtime.

For Tom Brady, it was a dream chance to impress. The ball was spotted at the New England 31 after a Lions punt. Two modest gains brought the Pats closer to but not across midfield, each tick of the clock making a delayed flight home more likely. Just when the team’s fate seemed certain, though, Brady reared back and hit receiver Sean Morey between the safeties, a 47-yard connection. Adam Vinatieri came on to make a chip shot field goal on the next play, hitting the netting with two seconds left, guaranteeing an escape from the Detroit suburbs.

Celebratory high-fives and back slaps awaited as Brady left the field, according to the Boston Globe. So did a gesture of gratitude from one teammate hip to the latest in portable technology.

“Those guys did not want to keep playing," Brady told the Globe. “One of the guys let me use his DVD player because he said, ‘At least you didn't keep me around for another half-hour.’ So that was nice.”

Bill Greene/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

When it comes to all that Brady has done in the two-plus decades since that night—his first extended NFL action after previously making a small cameo in the Patriots’ preseason opener against his childhood-favorite Niners—hindsight is 20/20. (Devotees of his pricey performance supplements and “recovery pajamas” might prefer TB12/TB12.) Now 44, he is the NFL’s only quadragenarian heading into the 2021 season, the latest in a career so absurdly long that all but 16 of his current teammates on the Buccaneers’ 80-man roster are as close in age, or closer, to Brady’s 14-year-old son Jack (who has been tagging along with Pops to practice as a guest ball boy at Tampa Bay’s training camp this summer) than they are to their quarterback.

Ten Super Bowl appearances and seven increasingly bejeweled rings later, the usual Brady narrative picks up in 2001 when he takes over for Drew Bledsoe and tucks the Lombardi Trophy, among other things, under his arm; the 2000 season is a forgotten footnote in his arc. And for good reason: Aside from his game-winning drive in Detroit, Brady did next to nothing else memorable on the field as a rookie, squeaking onto the active roster when coach Bill Belichick made the unusual decision to keep four quarterbacks. While Brady finished the season as Drew Bledsoe’s backup, he completed a single 6-yard pass in his lone regular-season appearance—Week 13 mop-up duty during a lopsided loss in, coincidentally, the Silverdome.

Even his crowning moment, the dart to Morey, is mostly lost to history; requests for surviving footage to the Lions, the Patriots and NFL Films turned up empty, while Brady “really didn’t have much recollection” of the 13–10 victory, according to a Bucs spokesperson.

But bits of that memory—of Brady’s first NFL heroics—linger for some former teammates. Among them is Eric Bjornson, a tight end who was watching from the sidelines when Brady hit Morey up the seam. “It just seemed like such a mature throw for a kid in his first year,” Bjornson says. “Late-game like that, guys usually don’t take a ton of risk … He fired that thing right down the throat of the defense. Five-step drop, no shuffle, no nothing, just … BANG! Like you’ve seen him do a thousand times, but this was the first sign of how calm, cool and confident he was that we were going to win.”

As it was happening, Bjornson had no reason to believe Brady’s throw would signal anything of note, save for a chance for the rookie who played college ball in nearby Ann Arbor—a sixth-rounder and the seventh draft pick of the Belichick era then buried on the depth chart behind Bledsoe, Michael Bishop and John Friesz—to bank some quality NFL game film. “I don’t remember much, but I remember being happy that this would open up a door for him to land somewhere else,” Bjornson says. “I didn’t think in 8 million years that he’d make the team.”

Two-plus decades later, it is perhaps a measure of Brady’s status that Bjornson and other members of the 2000 Patriots—all of them having long since retired from football and moved on to other lines of employment (Bjornson works in employee benefits consulting)—can recall anything at all about his rookie season. But they do. Like how he handled the task of performing skits during training camp. “One night, Tom was just up there doing stand-up, telling jokes,” Bjornson says. “It was pretty damn funny.” And how he looked with that shaved head. “Completely ridiculous,” Chris Eitzmann, also a tight end on that 2000 team, says

And his relative lack of fame, even among locals. “He’d be trying to talk to girls at the bars and they wouldn’t give him the time of day, and we’d all be laughing about it,” says defensive lineman David Nugent, who roomed with Brady for three years starting that preseason. “Obviously, that changed.”

Above all else, they remember the obsessive work ethic Brady brought every day, beginning when the rookie would pull his yellow Jeep Wrangler—“ugly and bright,” as Eitzmann describes the gift Brady received from an area car dealership upon making the team—into the parking lot before sunrise.

It was the same approach Brady summarized to the Globe that preseason, the week after the Detroit game: “I am going out there every day, trying to get better and see how good I can possibly be because there are a lot of great quarterbacks here,” he said. “It is so competitive that you just have to go out and worry about yourself, worry about completing balls when you are in, and hopefully get better each day.

“Then, hopefully, the coach sees something he can work with and then you are able to get your shot.”

Lonie Paxton was an undrafted long snapper from Sacramento State in 2000, thrilled to simply score an invitation to an NFL rookie camp, when he first met Brady on their shared connecting flight to New England. “I got a T-shirt and a plane ticket, so I was going to prove myself,” Paxton says. “I was not really expecting too much.” He quickly learned that his new traveling companion, the 199th pick that year, had similar plans. “He’s always had that chip on his shoulder,” Paxton says of Brady.

Eitzmann realized this soon after workouts started at Rhode Island’s Bryant University, by which point he and Brady had begun a tradition of staying late after practice to throw and run routes. “We’d go until I was completely gassed and couldn’t anymore,” Eitzmann says. One day, “We were walking off, and he was like, ‘Know what Eitz, I’m gonna beat out Bledsoe.’ Which at the time just sounded like the most preposterous thing ever. Bledsoe was a god in New England, and here’s this skinny kid.”

Carlos Osorio/AP Photo

Absent any meaningful reps to prove himself, Brady did whatever he could to get ahead. “He’d always be out there throwing, running ... everything,” receiver Shockmain Davis says. Bjornson remembers his preseason roommate, Friesz, coming home to gush about the meticulously detailed “works of art” that Brady would draw in the quarterback room when quizzed by a coach. Others recall him staying up to study the playbook in his temporary lodging at the End Zone Motel in Foxboro, Mass., tuning out the live concerts the divey establishment hosted on weekends. “His drive to get better was insane,” Eitzmann says. “He’s probably the most competitive person I’ve ever met.”

The football field wasn’t Brady’s only arena here. “Nintendo, Ping-Pong, pool, you beat him and he was pissed,” Eitzmann says. Later that year, when Brady was living with Eitzmann and Nugent in a condo he bought from cornerback Ty Law, the trio regularly staged double-elimination tournaments in Tecmo Super Bowl. A Bay Area native, Brady would play as the Niners, while Eitzmann often elected for the Raiders, featuring an unbeatable Bo Jackson. “He’d throw the controller against the wall,” Eitzmann says. “He wouldn’t talk to me for half a day.”

Despite his best efforts Brady remained a glorified practice squad player most of that season, taking snaps sparingly and staying home for away games. But it was clear that he had caught the attention of veteran peers, if only judging by Bledsoe's pranks targeting the yellow Jeep. “At one point he filled it with packing peanuts; at one point there was flour in the vents,” Eitzmann says. All the while, Brady’s intensity never waned. “Every night, he would go down to our basement and watch film, preparing like he was the starting quarterback,” Nugent says. “Then I wouldn’t see him in the morning, because he’d get up so early and go to the stadium and watch film before anyone else got there.”

One night, after returning from a road trip, Nugent checked in to see how Brady, no stranger to quarterback competition due to his time at Michigan, was handling the lack of action. “I asked him, ‘You hanging in there?’ ” Nugent recalls. “He was so competitive, but so far down the depth chart. He said, ‘You know, I can’t control how much practice time I get, or how the guys in front of me play. All I can control is how much I study, what I do with the one or two reps they give me. And when my time comes, I’ll be ready.”

Pats fans everywhere can recite what happened next by rote: Bledsoe went down in Week 2 of the 2001 season, sustaining severe internal injuries on a hit that hastened his exit from New England; Brady stepped up and soon became the youngest Super Bowl–winning quarterback ever, assuming the unfamiliar role of local deity, much to his—and everyone else’s—surprise “I’ve got all sorts of stories about him getting standing ovations at Outback Steakhouse, getting recognized as we were heading into the playoffs,” Nugent says. “At the time it was brand-new to him. We’d get back in the car and he’d be freaking out.”

• In the Shadow of Tom Brady: What It Means to Be Pick 199

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

• How the Bucs Are Leading a Linebacker Revival

• Magnificent Seventh: How Brady’s Bucs Became Super Bowl Champions

0 Comments