It’s been 16 years since the NFL champion has run it back. Two title-winning coaches explain the challenge facing Brady and the Bucs.

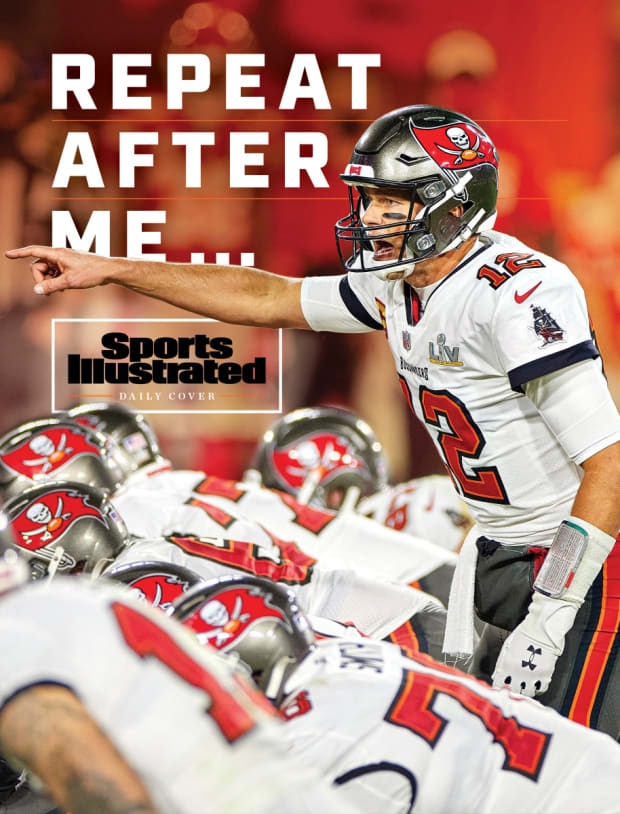

When the NFL season opens tonight, the Buccaneers will pursue a goal that is both entirely realistic and extremely unlikely: Win a second consecutive Super Bowl.

General manager Jason Licht called his shot in February, at Tampa Bay’s boat parade: "We’ve got the resources to keep all of you guys together, and to keep you next year, and we’re gonna f------ win this thing again next year.” Perhaps the alcohol was talking, but the checks came next.

The Bucs did what seemed impossible in the free-agency era: Return all 22 starters on offense and defense, along with their punter, their kicker, their head coach, and all three coordinators. They have the same owners. They play in the same stadium. They also appear to have one of the easiest schedules in the sport. Two of their division rivals are starting retread quarterbacks; the third, Atlanta, went 4–12 last year.

Oh, and they have the most accomplished quarterback of all time.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

A year ago, during the peak of the pandemic, Tampa Bay was trying to

hastily assemble a contender in a limiting environment. Now it begins the season as the most stable contender in the sport.The more you think about it, the easier it is to see it repeating. And yet: The last 15 champions failed to repeat. That, by far, is the longest stretch without back-to-back champions in NFL history.

In those 15 years, only three champions have made it back to the Super Bowl the following year. Only five won a playoff game. Five missed the playoffs. The streak has lasted so long that we have gotten used to it, but it is still astounding. Previously, the longest stretch without a repeat champion was nine years (1980 to ’88 seasons). From 1989 to 2004, four franchises repeated as champions: the 49ers, Cowboys, Broncos and Patriots. Since then, nobody has done it.

The Bucs have already made history by becoming the first team to play in (and then win) a Super Bowl in their home stadium. But that streak was not as mysterious as it was often portrayed. The Patriots, Steelers, Cowboys, 49ers, Packers, Giants, Broncos and Washington have won 33 Super Bowls and hosted three. The teams that usually hosted Super Bowls usually stunk.

Now? Well, with so much roster movement from year to year, it’s easy to see repeating in this era is hard. But why is it so hard?

In 1997, after Brett Favre led the Packers to three playoff routs and a Super Bowl win, coach Mike Holmgren says he “kind of made it my message to the team: ‘Listen, it’s gonna be harder.’ You go in with the same team and the idea that we can do this again. But things change.”

Holmgren changed first. He canceled his TV show in Green Bay, to show his players that he was even more focused on football than he had been the year before. Still, just as Favre was the MVP but occasionally careless, the Packers were a juggernaut that could self-destruct.

“A lot of times, that offseason, if they’re not careful, everybody starts thinking they’re the greatest thing since sliced bread,” Holmgren says. “You get things entering the picture that take away from what you’re trying to accomplish.”

Those players (and their agents) often want new contracts, and they tend to ask for more than their team thinks they are worth. With a salary cap, free agency and a draft order that rewards the worst teams, the modern NFL is designed to distribute and redistribute talent relatively evenly. The Bucs skillfully navigated this last offseason when they re-signed their seven key free agents.

“There is always another group coming up,” Holmgren says. “You got players who are under contract going into the last year of their deal. With the money, it’s really different now. You can’t pay everybody, not like that.”

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

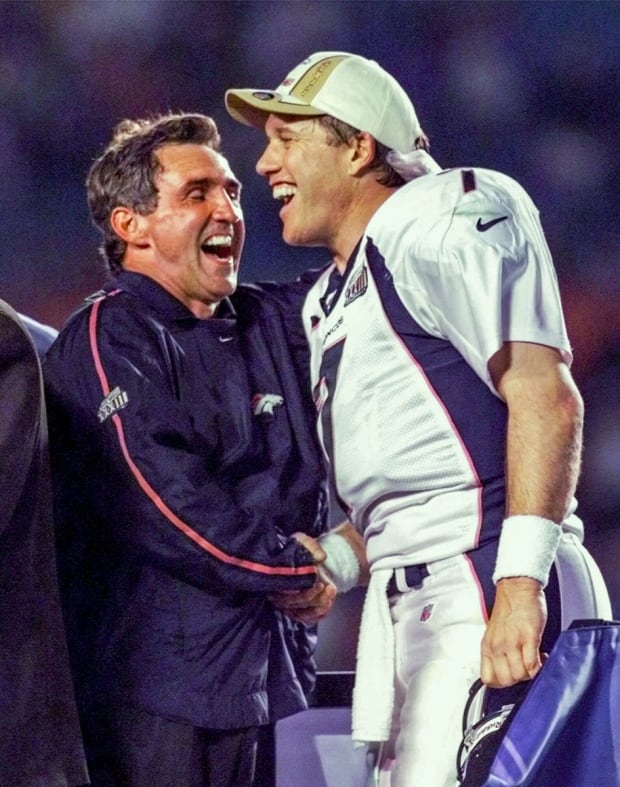

Holmgren’s Packers went 13–3 and made it back to the Super Bowl. But when they got there, they faced Denver, a team with a history of losing big games—three Super Bowls with John Elway, but also a stunning playoff loss to the expansion Jaguars the year before.

“I had a heck of a time convincing our guys [the Broncos] were really good,” Holmgren says. “I tried every trick in the book. I yelled; I patted them on the rear. That stuck with me for a long time: What could I have done? I have thought about it a lot. We were practicing O.K. But compared to other Super Bowls I had coached in, it wasn’t quite what I wanted.”

The Broncos beat the Packers, 31–24. Now Denver coach Mike Shanahan faced the same challenge Holmgren had faced the year before. He decided to dangle an innovative incentive that would get the attention of any workplace: succeed, and Mondays would be an off day.

They are called Victory Mondays and are commonplace (though not universal) in the NFL these days. Shanahan’s team was the first to implement them. He says now that he had ulterior motives: “The players thought it was great [but] it was more for the coaches, so we could get to our game plan right away.” But it was a masterly move for a coach who had to make sure his players, who were already champions, had a reward in sight every week.

If winning the Super Bowl requires everything you have, winning another requires more of it.

“I think that it is so hard when people are shooting for you,” Shanahan says. “You better have a good team. And you better be lucky with injuries. We were very fortunate with injuries the second year. Even the first year we won it, we were pretty injury-free.”

Having great injury luck for two straight years, Shanahan says, “never happens. We were lucky enough that it did happen to us.” Holmgren thinks Tampa Bay has a better chance of staying healthy than teams from a generation ago: “Quite honestly how teams are practicing now, it’s a different thing. Players get rested. They have days off. We never did that. That wasn’t part of the deal. I didn’t grow up that way.”

Amy Sancetta/AP/Shutterstock

Still, if this year’s Bucs earn a first-round bye and win the NFC championship, the Super Bowl will be their 40th game in two seasons. Play that much football, and somebody will get hurt. “Heaven forbid,” Holmgren says, “something happens with Brady.”

Their biggest challenge might be entering January in the proper psychological state.

Shanahan’s Broncos had some similarities to this year’s Bucs. Shanahan, like Bruce Arians, was a brilliant offensive mind on his second head-coaching job. Broncos quarterback John Elway, like Tom Brady now, was a legendary quarterback who was near the end of his career.

What they really had, though, was the right psychological state entering the playoffs. Victory Mondays might have played a role in keeping the team focused, but Shanahan says, “Our players knew that people would be ready for us. We had a lot of veterans, a lot of guys that kind of took control of practices, took control of games. It was really a team with a lot of maturity.”

By the time the playoffs started, Shanahan says, “I never felt more sure about a football team, just because of the leadership that we had. And they actually dominated those playoff games.”

It seems silly to use valuable hot-take time on the first day of the season to speculate on the psychological state of the Bucs in four months. But that is sort of the point. Even Tampa Bay can’t worry about that right now, but it will be a primary driver in whether it repeats.

Quite a few teams have looked primed to win another title until they didn’t. After stunning the undefeated Patriots in Super Bowl XLII, the 2008 Giants won 11 of their first 12 games. They lost in the first round of the playoffs. The ’11 Packers went 15–1 as defending champs, then lost in the first round, too.

But Brady won’t let them get complacent, you say. You are probably right. As Shanahan says, “When you have those quarterbacks and you have the right guy, you know they can take control of that football team just by the way they handle themselves.”

The problem is, even if the Bucs stay healthy and motivated and enter January in the right frame of mind, they need something else: “You still,” Holmgren says, “have to be a little lucky.”

Champions (and their fan bases) don’t want to hear they were lucky. But good fortune is part of sports. Nobody wins a title solely because of luck, but as Holmgren says, “It kind of has to fall your way a little bit.”

Lost in all the excitement about the Bucs bringing back everybody from their Super Bowl–winning team is this annoying little nugget: Last year, they weren’t that great. Yes, they were clearly deserving champions. But they were underdogs in three of their four playoff games. They did not win their division. They went 11–5 in the regular season. Every team that repeated in the last 50 years had a record better than 11–5 in both seasons, except one: Joe Montana’s 49ers, who went 10–6 in 1988. But those 49ers were in the midst of a four-season stretch when they won 51 games.

The Bucs were very good. They were opportunistic. And they were lucky.

In the wild-card game, they faced one of the worst teams in playoff history: a Washington team that finished 7–9 and had a quarterback, Taylor Heinicke, who was making the second start of his career. The next week, the Bucs trailed by a touchdown with 20 minutes left in New Orleans before the tide turned with three Saints turnovers. Tampa Bay’s NFC championship win over the Packers was one of those bizarre games in which one team lost as much as the other team won—Green Bay gave away a touchdown at the end of the first half with a preposterously poor defensive call (Holmgren says, “It blew my mind”; Arians said after the game, “When we lined up, you could tell it was going to be a touchdown”).

Then, in the Super Bowl, the Bucs faced a Chiefs team that was missing both of its starting tackles, creating a huge matchup advantage for a Tampa Bay defense that chased Patrick Mahomes all night. As Shanahan said—speaking generally, not of Kansas City: “All of a sudden you lose one or two key players at the wrong time. That doesn't usually work out very good.”

Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated

The Bucs earned their title, and it is completely reasonable to call them the favorite to win another. But one is reminded of an exchange that Brady had with Tedy Bruschi in the middle of his Patriots run, after a tight playoff win over the Chargers.

“Man, that wasn't easy,” Brady told his teammate.

Bruschi replied: “They never are, buddy. They never are.”

• How the Bucs Are Leading a Linebacker Revival

• Inside Tom Brady's Forgotten Rookie Year

• Copycatting the NFL’s Trendiest Offense Is Harder Than You Think

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

It’s been 16 years since the NFL champion has run it back. Two title-winning coaches explain the challenge facing Brady and the Bucs.

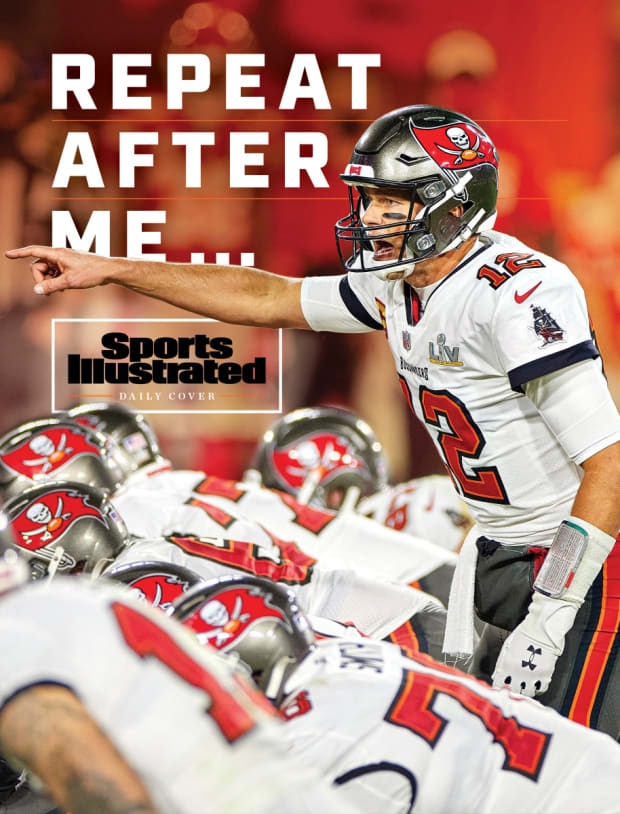

When the NFL season opens tonight, the Buccaneers will pursue a goal that is both entirely realistic and extremely unlikely: Win a second consecutive Super Bowl.

General manager Jason Licht called his shot in February, at Tampa Bay’s boat parade: "We’ve got the resources to keep all of you guys together, and to keep you next year, and we’re gonna f------ win this thing again next year.” Perhaps the alcohol was talking, but the checks came next.

The Bucs did what seemed impossible in the free-agency era: Return all 22 starters on offense and defense, along with their punter, their kicker, their head coach, and all three coordinators. They have the same owners. They play in the same stadium. They also appear to have one of the easiest schedules in the sport. Two of their division rivals are starting retread quarterbacks; the third, Atlanta, went 4–12 last year.

Oh, and they have the most accomplished quarterback of all time.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

A year ago, during the peak of the pandemic, Tampa Bay was trying to hastily assemble a contender in a limiting environment. Now it begins the season as the most stable contender in the sport.

The more you think about it, the easier it is to see it repeating. And yet: The last 15 champions failed to repeat. That, by far, is the longest stretch without back-to-back champions in NFL history.

In those 15 years, only three champions have made it back to the Super Bowl the following year. Only five won a playoff game. Five missed the playoffs. The streak has lasted so long that we have gotten used to it, but it is still astounding. Previously, the longest stretch without a repeat champion was nine years (1980 to ’88 seasons). From 1989 to 2004, four franchises repeated as champions: the 49ers, Cowboys, Broncos and Patriots. Since then, nobody has done it.

The Bucs have already made history by becoming the first team to play in (and then win) a Super Bowl in their home stadium. But that streak was not as mysterious as it was often portrayed. The Patriots, Steelers, Cowboys, 49ers, Packers, Giants, Broncos and Washington have won 33 Super Bowls and hosted three. The teams that usually hosted Super Bowls usually stunk.

Now? Well, with so much roster movement from year to year, it’s easy to see repeating in this era is hard. But why is it so hard?

In 1997, after Brett Favre led the Packers to three playoff routs and a Super Bowl win, coach Mike Holmgren says he “kind of made it my message to the team: ‘Listen, it’s gonna be harder.’ You go in with the same team and the idea that we can do this again. But things change.”

Holmgren changed first. He canceled his TV show in Green Bay, to show his players that he was even more focused on football than he had been the year before. Still, just as Favre was the MVP but occasionally careless, the Packers were a juggernaut that could self-destruct.

“A lot of times, that offseason, if they’re not careful, everybody starts thinking they’re the greatest thing since sliced bread,” Holmgren says. “You get things entering the picture that take away from what you’re trying to accomplish.”

Those players (and their agents) often want new contracts, and they tend to ask for more than their team thinks they are worth. With a salary cap, free agency and a draft order that rewards the worst teams, the modern NFL is designed to distribute and redistribute talent relatively evenly. The Bucs skillfully navigated this last offseason when they re-signed their seven key free agents.

“There is always another group coming up,” Holmgren says. “You got players who are under contract going into the last year of their deal. With the money, it’s really different now. You can’t pay everybody, not like that.”

Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated

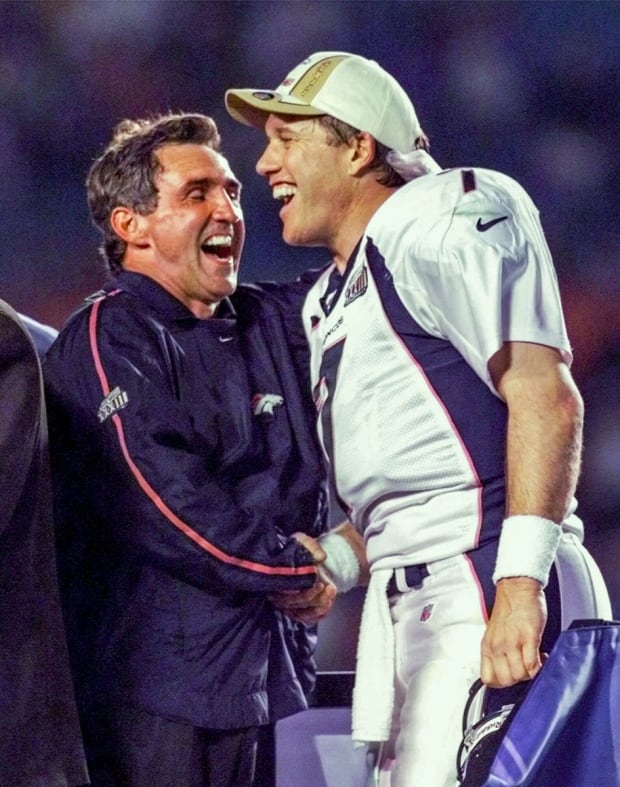

Holmgren’s Packers went 13–3 and made it back to the Super Bowl. But when they got there, they faced Denver, a team with a history of losing big games—three Super Bowls with John Elway, but also a stunning playoff loss to the expansion Jaguars the year before.

“I had a heck of a time convincing our guys [the Broncos] were really good,” Holmgren says. “I tried every trick in the book. I yelled; I patted them on the rear. That stuck with me for a long time: What could I have done? I have thought about it a lot. We were practicing O.K. But compared to other Super Bowls I had coached in, it wasn’t quite what I wanted.”

The Broncos beat the Packers, 31–24. Now Denver coach Mike Shanahan faced the same challenge Holmgren had faced the year before. He decided to dangle an innovative incentive that would get the attention of any workplace: succeed, and Mondays would be an off day.

They are called Victory Mondays and are commonplace (though not universal) in the NFL these days. Shanahan’s team was the first to implement them. He says now that he had ulterior motives: “The players thought it was great [but] it was more for the coaches, so we could get to our game plan right away.” But it was a masterly move for a coach who had to make sure his players, who were already champions, had a reward in sight every week.

If winning the Super Bowl requires everything you have, winning another requires more of it.

“I think that it is so hard when people are shooting for you,” Shanahan says. “You better have a good team. And you better be lucky with injuries. We were very fortunate with injuries the second year. Even the first year we won it, we were pretty injury-free.”

Having great injury luck for two straight years, Shanahan says, “never happens. We were lucky enough that it did happen to us.” Holmgren thinks Tampa Bay has a better chance of staying healthy than teams from a generation ago: “Quite honestly how teams are practicing now, it’s a different thing. Players get rested. They have days off. We never did that. That wasn’t part of the deal. I didn’t grow up that way.”

Amy Sancetta/AP/Shutterstock

Still, if this year’s Bucs earn a first-round bye and win the NFC championship, the Super Bowl will be their 40th game in two seasons. Play that much football, and somebody will get hurt. “Heaven forbid,” Holmgren says, “something happens with Brady.”

Their biggest challenge might be entering January in the proper psychological state.

Shanahan’s Broncos had some similarities to this year’s Bucs. Shanahan, like Bruce Arians, was a brilliant offensive mind on his second head-coaching job. Broncos quarterback John Elway, like Tom Brady now, was a legendary quarterback who was near the end of his career.

What they really had, though, was the right psychological state entering the playoffs. Victory Mondays might have played a role in keeping the team focused, but Shanahan says, “Our players knew that people would be ready for us. We had a lot of veterans, a lot of guys that kind of took control of practices, took control of games. It was really a team with a lot of maturity.”

By the time the playoffs started, Shanahan says, “I never felt more sure about a football team, just because of the leadership that we had. And they actually dominated those playoff games.”

It seems silly to use valuable hot-take time on the first day of the season to speculate on the psychological state of the Bucs in four months. But that is sort of the point. Even Tampa Bay can’t worry about that right now, but it will be a primary driver in whether it repeats.

Quite a few teams have looked primed to win another title until they didn’t. After stunning the undefeated Patriots in Super Bowl XLII, the 2008 Giants won 11 of their first 12 games. They lost in the first round of the playoffs. The ’11 Packers went 15–1 as defending champs, then lost in the first round, too.

But Brady won’t let them get complacent, you say. You are probably right. As Shanahan says, “When you have those quarterbacks and you have the right guy, you know they can take control of that football team just by the way they handle themselves.”

The problem is, even if the Bucs stay healthy and motivated and enter January in the right frame of mind, they need something else: “You still,” Holmgren says, “have to be a little lucky.”

Champions (and their fan bases) don’t want to hear they were lucky. But good fortune is part of sports. Nobody wins a title solely because of luck, but as Holmgren says, “It kind of has to fall your way a little bit.”

Lost in all the excitement about the Bucs bringing back everybody from their Super Bowl–winning team is this annoying little nugget: Last year, they weren’t that great. Yes, they were clearly deserving champions. But they were underdogs in three of their four playoff games. They did not win their division. They went 11–5 in the regular season. Every team that repeated in the last 50 years had a record better than 11–5 in both seasons, except one: Joe Montana’s 49ers, who went 10–6 in 1988. But those 49ers were in the midst of a four-season stretch when they won 51 games.

The Bucs were very good. They were opportunistic. And they were lucky.

In the wild-card game, they faced one of the worst teams in playoff history: a Washington team that finished 7–9 and had a quarterback, Taylor Heinicke, who was making the second start of his career. The next week, the Bucs trailed by a touchdown with 20 minutes left in New Orleans before the tide turned with three Saints turnovers. Tampa Bay’s NFC championship win over the Packers was one of those bizarre games in which one team lost as much as the other team won—Green Bay gave away a touchdown at the end of the first half with a preposterously poor defensive call (Holmgren says, “It blew my mind”; Arians said after the game, “When we lined up, you could tell it was going to be a touchdown”).

Then, in the Super Bowl, the Bucs faced a Chiefs team that was missing both of its starting tackles, creating a huge matchup advantage for a Tampa Bay defense that chased Patrick Mahomes all night. As Shanahan said—speaking generally, not of Kansas City: “All of a sudden you lose one or two key players at the wrong time. That doesn't usually work out very good.”

Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated

The Bucs earned their title, and it is completely reasonable to call them the favorite to win another. But one is reminded of an exchange that Brady had with Tedy Bruschi in the middle of his Patriots run, after a tight playoff win over the Chargers.

“Man, that wasn't easy,” Brady told his teammate.

Bruschi replied: “They never are, buddy. They never are.”

• How the Bucs Are Leading a Linebacker Revival

• Inside Tom Brady's Forgotten Rookie Year

• Copycatting the NFL’s Trendiest Offense Is Harder Than You Think

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

0 Comments