How a high school football team felt the first forceful ripple effects of a knee taken five years ago today.

From

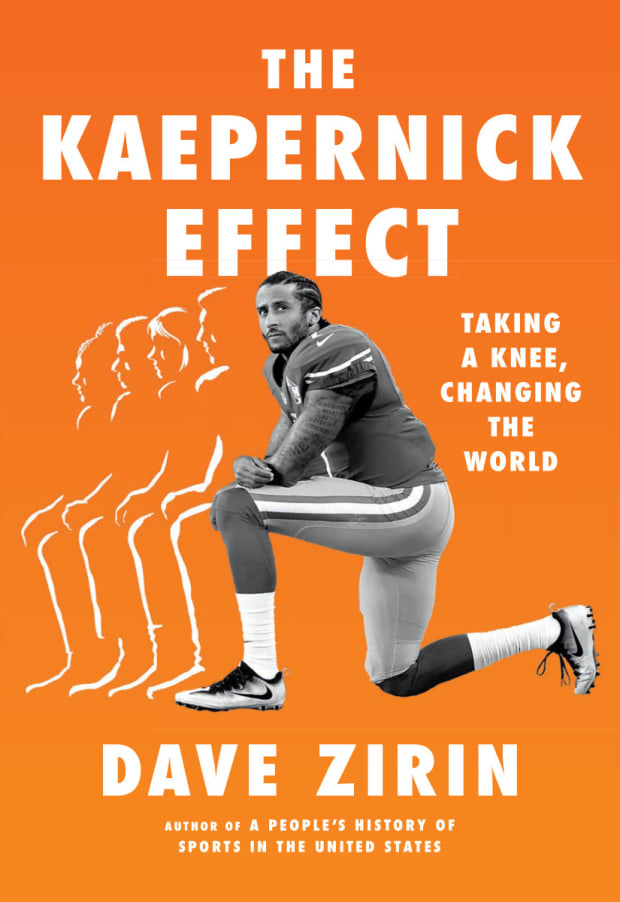

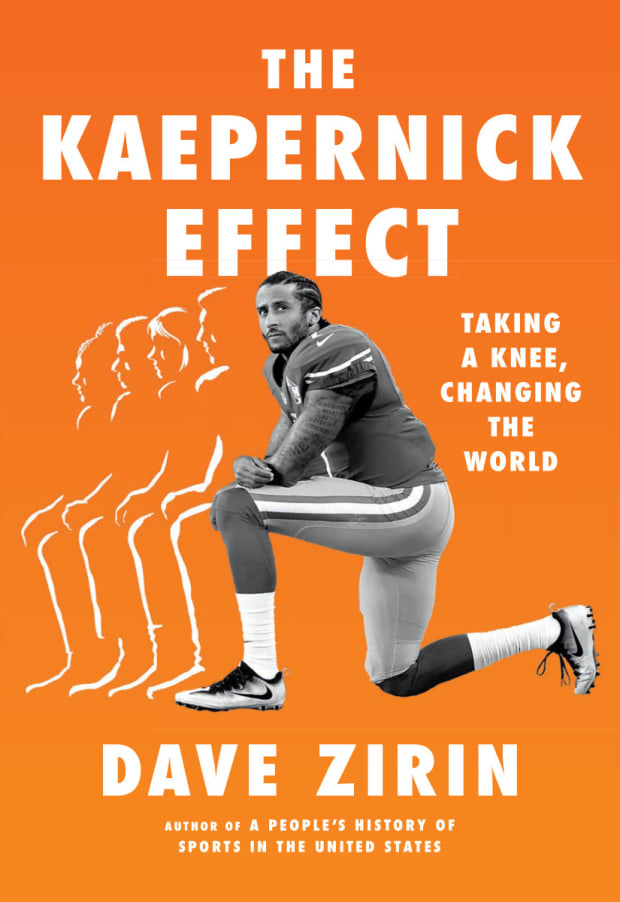

The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World, by Dave Zirin. Copyright © 2021 by Dave Zirin. Reprinted by permission of The New Press. All rights reserved.

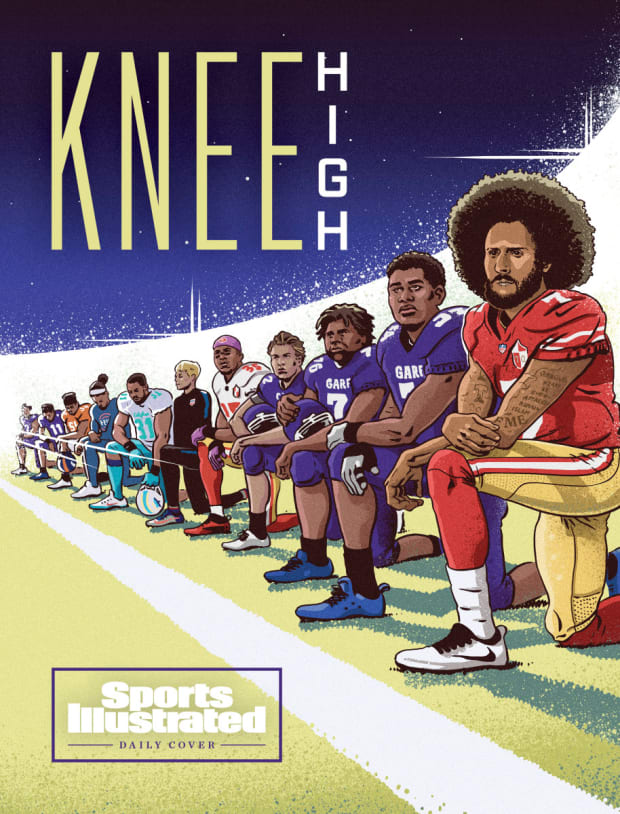

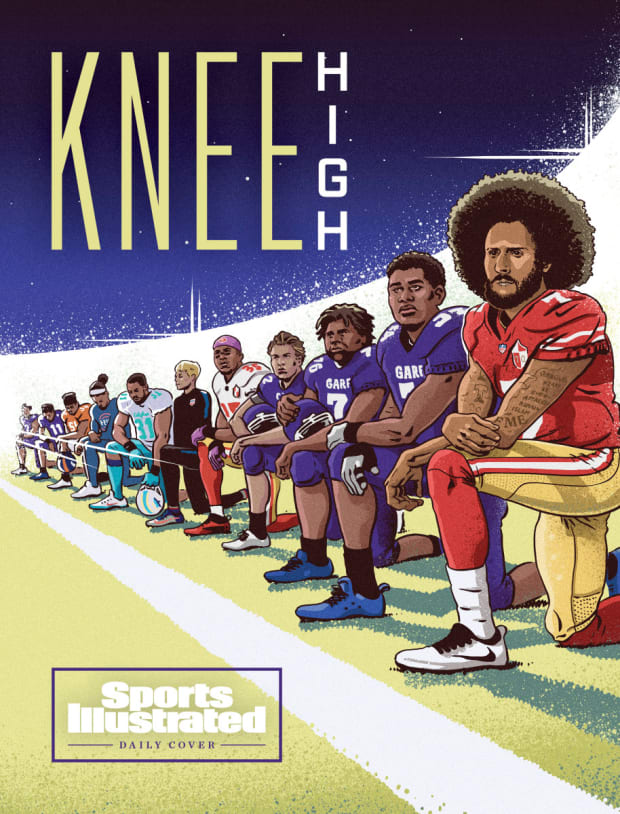

Illustration by Mateusz Kolek

It’s been five years since that fateful moment, before a little-seen preseason game between the 49ers and the Chargers on Sept. 1, 2016, when Colin Kaepernick refused to stand for the national anthem,srp in protest of police violence. The ensuing controversy, and the ways in which it provoked both national outrage and global solidarity, have been much discussed. But little has been said about the true “Kaepernick Effect”: the various ways that young athletes took the quarterback’s method of protest—kneeling during the anthem—and brought it to their own communities in order to spark discussions about racial inequities. Their efforts did not always go smoothly, and they often produced more heat than light. Here is one of those stories:

James A. Garfield High in Seattle is a place where you can feel the history thrum through the hallways. Quincy Jones and Jimi Hendrix were students here. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke on the grounds. It’s always been a fulcrum of debate, culture and big-time high school sports. It makes sense that it was the first place in the country where an entire team took a knee. But it wasn’t all garlands and glory.

Garfield’s football coach at the time, Joey Thomas, was at the heart of what went down. He’s now coaching in Florida, and the first thing he said when we spoke recently was, “I saw in your email that you wanted to talk about Garfield High School and the process by which the team took a knee. What part of the process do you want to talk about? Do you want to talk about the part where they tried to fire me? The part where they tried to take my job away? The part where I finally resigned? We were the only school that unanimously did this. This came with a bunch of death threats and a whole bunch of other poo-poo.”

I did in fact want to hear about all the other poo-poo.

To understand what happened, you need to start by understanding that Garfield is a school deeply tied to coach Thomas’s life. He grew up in Seattle, in the Central District, the same neighborhood where Garfield resides. “For me, that is home,” he says. “I played at the University of Washington, later transferred to Montana State, where I was an All-America, and I went on to play five years in the NFL. I came home after I retired due to injury, and I went straight into teaching and learning. Yes, we won games, and yes, that’s phenomenal, but it’s about empowering the lives of the youths. Our greatest message to them is, ‘You are the future, but we have to grow you, nurture you and develop you mentally, so when you leave this program you can have a good foundation.’ School’s put in place not to educate. It’s to make you comply. So our job was to push back against that—educate kids and also listen to them. Kids are so much smarter than what we give them credit for.”

Coach Thomas’s thoughts about policing were formed by his own life in the Central District. “When you grow up and you’re 5 or 6 [years old], hey, the police are going to give you candy,” he remembers thinking. “You run to the police when things are bad. Hey, officer, I need some help. I think that wore off around fifth grade. There’s not one particular incident, but at that point you’re no longer naive that everything’s O.K. The sky is blue, the grass is green, the police are the police. This is how life is.”

The process that brought the Garfield football team to taking a knee and making national headlines began, Thomas says, with one player who approached him the day before a game and said, “Coach, this Kaepernick thing is crazy. Man, let’s take a knee.”

Thomas nixed that; the team, he said, needed to have a conversation before they took such a step. Then the next week another player asked about Kaepernick, and that led to the squad having a dialogue. Says Thomas: “We talked it out. What was [Kaepernick] doing? Why was he doing it? What does that mean to them? A lot of the kids said, ‘I don’t quite understand it.’ So we talked about the national anthem’s third verse and what that third verse really means. I had them read it out loud and told them: ‘You tell me what it means.’ Young men always ask, ‘What do you think?’ but my job is to help them become critical thinkers, not think for them. I said, ‘What do you think? Let’s read it out loud until you have a greater understanding.’ Each individual came to the belief that, hey, when they’re talking about these liberties and justices, they’re not speaking about me.”

The third verse, never sung before sporting events, reads in part:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave

This was in reference to the enslaved Black Americans who, promised freedom by the British, escaped bondage and joined the British army in the War of 1812. The anthem’s writer, Francis Scott Key, by many interpretations, was taking triumphant joy in the deaths of the enslaved. (This “joy” may have been influenced by the fact that Key was himself a slave owner.) In the last two lines, Key takes a wrecking ball to irony by declaring that the escaped enslaved people killed on the battlefield while fighting for their liberation is further proof of the glory of the “land of the free and the home of the brave.” As journalist Jon Schwarz wrote: “Maybe it’s all ancient, meaningless history. Or maybe it’s not, and Kaepernick is right, and we really need a new national anthem.”

The Garfield players, armed with this history, were ready to take that knee. Was Thomas nervous before they did it? He says, “No, I wasn’t—because, to be honest, I didn’t understand the gravity of the situation. I don’t think anyone understood what lay ahead or what would come from this. I saw it as an educational opportunity, to stand by and support these young men as they grow and find themselves. I didn’t think it was a big deal. The kids felt like doing something righteous, and what type of educator would I be if I didn’t support that? They weren’t hurting anyone. It wasn’t damaging anything. It wasn’t disrespectful. It wasn’t harmful. I just saw that these kids strongly believe this. This is what it is. If I’m wrong, then I’m wrong, but I’m supporting my kids.”

The backlash against Garfield came from all corners. “We had death threats,” Thomas says. “The kids were told that they were never going to get into college. People said they would do everything they could to make sure they wouldn’t get in through admissions. I was called every name in the book. And my tires were slashed at my house. This is my home. My wife and kids are there. My residence! I had to move because people knew where I lived.”

The way Thomas describes it, the district, Seattle Public Schools, felt the backlash and wanted Garfield’s football team to stop kneeling. They blamed Thomas, he says, and he paid for it with his job. First they charged him with a bogus recruiting violation, of which he was quickly cleared, and then the school tried to change his job title. Eventually, the harassment became too much and Thomas left the school to which he had dedicated so much of his life. “They were definitely trying to force me out, one way or the other,” he says. (Representatives for Seattle Public Schools and Garfield High declined to comment.)

Michael Zagaris/San Francisco 49ers/Getty Images

Now Joey Thomas is far from the place he called home, working at Florida Atlantic University, where he’s the receivers coach. “Obviously, the stance we took was unpopular,” he says. “Do I think it’s hurt me professionally? Without question. Was I hesitant to [talk about it]? Without question. But right is right and wrong is wrong. Am I still concerned about backlash at this point? Yeah, of course I am, because I already experienced it. It’s been shown to me what can happen.”

Thomas says of his players, “Everybody’s proud they did it, because we understand in hindsight that we were part of history. But it’s very important for people to understand: We didn’t know it was going to be like this. We didn’t plan on it being like this. We were just Garfield. We were just a high school in Seattle, standing for what we believed in. Before we knew it, we were in USA Today, the L.A. Times, Time magazine. ... Who saw that coming? The misconception was that we wanted the attention. Man, we didn’t ask for any of that. I sure didn’t ask to be catapulted to the front seat. But I think it was a comfortable narrative for people to push.

“Here’s the key: [Kneeling] was a student-led thing. But it was convenient for the powers that be to say it was coach-led, because then they’re able to give it a face. When it’s student-led, you can’t do that. And as a coach, you can’t do anything but support your kids. So, I think there was a conscious effort to deface what was going on and put a spin on it. In the end, that’s what cost me. But, hey, I would do it again. I’m always going to fight for what I believe in, but pushing what I believe was never the goal. The intention was to show these young men that they have a voice, that they are important, that they matter.”

Being attacked from all corners also brought the team and the school together. “Even though we did get support from everybody in our community, there was a long period of time when we were lonely and we were by ourselves,” says Thomas. “I think it’s always easier when people see other people supporting—they jump on the bandwagon. But there were some lonely days, some lonely weeks. Before it was popular to kneel with Kap, we were there. And, believe me, it was quite unpopular.”

Jelani Howard was part of that team. Seeing the gentrification taking place throughout Seattle—the creation of wealthy neighborhoods where he was clearly not wanted—was something that changed him when he was growing up. Like so many young people in what we could call “Generation Trayvon,” he hurtled toward becoming a changemaker when Trayvon Martin was murdered by George Zimmerman. “That’s when I started realizing, Oh, this is actually real,” Howard says. “Before that, I never thought of police brutality or anything like that. That’s when I really opened my eyes.”

Howard has his own story about how Garfield made its small piece of history. “It all started,” he says, “because coach Thomas used to have these talks with us in the summer about what’s going on in the world, before we’d even go to practice or watch film. [Donald] Trump was running for office and we were talking about what was going on. Then, during preseason, Kaepernick took a knee, and after that game we talked about why he did it. That led us on to other conversations. We started talking about how other verses of the national anthem talked about killing slaves. It all started with conversations ... connecting it to what’s going on in the world.”

Buy The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World

After the high schoolers took a knee, Kaepernick spoke about it to The Seattle Times, saying: “We have a younger generation that sees these issues and want to be able to correct them. I think that’s amazing. I think it shows the strength, the character and the courage of our youth. Ultimately, they’re going to be needed to help make this change.”

What made Garfield exceptional—and what caught Kaepernick’s attention—was that, as Howard remembers, “It was the whole team—even the managers and cheerleaders started taking a knee.” It all made national news, but that meant a national backlash. “At first we had a Facebook picture of our entire team. People would comment on it, saying nasty or disrespectful things. Then there was the one morning where [coach Thomas] didn’t show up and everybody was just confused. He finally got there like an hour late, and he told us that somebody had slashed his tires. That’s when everybody knew: Wow, this is real. People are really mad about us doing this.”

As for regrets, Howard says, “I have none. It’s something that I’ll always be able to tell my kids about. I did something I will always remember. ... Nobody thought that 15-, 16-, 17-year-old kids would be able to help lead a movement. I have no regrets because we had a motivation: We wanted to see social equality for everybody because we live in a society where, if you’re a person of color, you’re already on the back burner. If there’s a Black person and a white person who have the same college degree, same everything, that white person will make more than that Black person, just based on race. That just doesn’t sit right with me. I want to be able to change that for the next generation.”

Howard has advice for others thinking about stepping forward and speaking out: “You have a voice and you should use it and you shouldn’t be scared of what people will say or what will happen. There are people who went before us, who went through way worse things than we’re going through now.”

Once the football team took a knee, it spread to other sports at Garfield High. Janelle Gary was on the softball team that joined in. She had played on a select team growing up, and she remembers how an umpire once made a snide remark about her being one of the few Black girls on the field. She was only 10 at the time. “That is something I’ll never forget,” she says.

Police violence, too, was something Gary was made aware of at a young age. But it wasn’t until social media highlighted the killing of Martin—and highlighted other Black people who’ve been affected by racial violence and police brutality—that it hit home. “Actually watching the videos myself,” she says, “brought it into reality for me.”

Ira L. Black/Corbis/Getty Images

Gary and her team at Garfield decided to protest during the anthem in part because of the backlash the football team had taken—especially Thomas. “People were threatening him and his children,” she remembers. “We wanted to stand up by taking a knee. ... We wanted to show solidarity, not only with Colin Kaepernick, but also to support our football team—to show that Garfield believes in this together.”

She describes a team that “was the most diverse that made it to state; an inner-city school [that] had the most people of color,” and whose students and faculty are often on the front lines of social justice movements in Seattle. The softball team was united in its decision to take a knee.

“During [that first] game,” Gary says, “one parent was antagonizing us and making comments every time we went up to bat. That was a lot for us to take in, having parents from the stands yell at you. [Afterward, on] our lunch break, a bunch of parents from other schools found us and went out of their way to keep on yelling: ‘Shame on you, Garfield! Shame on you!’ No one asked why we were doing it. They just attacked us. It was really hard, at that age. We were very emotional. We didn’t think people would attack kids like that.”

If Gary could do it all over again, she says she would. “People say negative things to try to scare you, but if you’re able to persevere through that, like in the days of the civil rights movement, you’re going to see more change. They are trying to stop a movement, because they know how big it can become.”

Two years after kneeling during the national anthem, Gary and the Garfield softball team won the state championship. “I think that was our sweet revenge,” she says. “I did appreciate being the first inner-city school to win state.”

Gary also helped start an organization, New Generation, after the death of Charleena Lyles, a Seattle Public Schools mother who was shot and killed by the police. New Generation organized demonstrations and raised money for Lyles’s family, and the group worked closely with former NFL player Michael Bennett to make sure Lyles’s name wouldn’t be forgotten—“that people in our community know what’s going on,” Gary says.

Ron Hoskins/NBAE/Getty Images

Bigger picture, Gary ponders the political impact of Kaepernick and his protest, and she says: “Many people don’t like him, but you have to think that people didn’t like Dr. Martin Luther King or Malcolm X in their time, either, because they knew [these men] were starting a revolution. [Kaepernick] is getting people to talk, so you’re going to have people who love him and people who hate him. But I believe in 20 years he’ll be seen as one of the greatest. He’s given people hope. If it wasn’t for him, I really don’t think there’d be a conversation.

“Sometimes when you stick up for what you believe in, it upsets people. When they crack down on you taking a knee, or raising a fist, it shows they don’t want you to have hope. Especially being young, you need that hope to keep on going. ... I’m glad I experienced this all at a young age, so now I have a better understanding of what people are like. I’m glad we [knelt], and I’m glad we had someone like Colin Kaepernick to give us the courage to do that.”

• Tom Brady's Forgotten Rookie Year

• Dak Prescott's Heal Turn

• The Falcons, Depression and Me

How a high school football team felt the first forceful ripple effects of a knee taken five years ago today.

From The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World, by Dave Zirin. Copyright © 2021 by Dave Zirin. Reprinted by permission of The New Press. All rights reserved.

Illustration by Mateusz Kolek

It’s been five years since that fateful moment, before a little-seen preseason game between the 49ers and the Chargers on Sept. 1, 2016, when Colin Kaepernick refused to stand for the national anthem,srp in protest of police violence. The ensuing controversy, and the ways in which it provoked both national outrage and global solidarity, have been much discussed. But little has been said about the true “Kaepernick Effect”: the various ways that young athletes took the quarterback’s method of protest—kneeling during the anthem—and brought it to their own communities in order to spark discussions about racial inequities. Their efforts did not always go smoothly, and they often produced more heat than light. Here is one of those stories:

James A. Garfield High in Seattle is a place where you can feel the history thrum through the hallways. Quincy Jones and Jimi Hendrix were students here. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke on the grounds. It’s always been a fulcrum of debate, culture and big-time high school sports. It makes sense that it was the first place in the country where an entire team took a knee. But it wasn’t all garlands and glory.

Garfield’s football coach at the time, Joey Thomas, was at the heart of what went down. He’s now coaching in Florida, and the first thing he said when we spoke recently was, “I saw in your email that you wanted to talk about Garfield High School and the process by which the team took a knee. What part of the process do you want to talk about? Do you want to talk about the part where they tried to fire me? The part where they tried to take my job away? The part where I finally resigned? We were the only school that unanimously did this. This came with a bunch of death threats and a whole bunch of other poo-poo.”

I did in fact want to hear about all the other poo-poo.

To understand what happened, you need to start by understanding that Garfield is a school deeply tied to coach Thomas’s life. He grew up in Seattle, in the Central District, the same neighborhood where Garfield resides. “For me, that is home,” he says. “I played at the University of Washington, later transferred to Montana State, where I was an All-America, and I went on to play five years in the NFL. I came home after I retired due to injury, and I went straight into teaching and learning. Yes, we won games, and yes, that’s phenomenal, but it’s about empowering the lives of the youths. Our greatest message to them is, ‘You are the future, but we have to grow you, nurture you and develop you mentally, so when you leave this program you can have a good foundation.’ School’s put in place not to educate. It’s to make you comply. So our job was to push back against that—educate kids and also listen to them. Kids are so much smarter than what we give them credit for.”

Coach Thomas’s thoughts about policing were formed by his own life in the Central District. “When you grow up and you’re 5 or 6 [years old], hey, the police are going to give you candy,” he remembers thinking. “You run to the police when things are bad. Hey, officer, I need some help. I think that wore off around fifth grade. There’s not one particular incident, but at that point you’re no longer naive that everything’s O.K. The sky is blue, the grass is green, the police are the police. This is how life is.”

The process that brought the Garfield football team to taking a knee and making national headlines began, Thomas says, with one player who approached him the day before a game and said, “Coach, this Kaepernick thing is crazy. Man, let’s take a knee.”

Thomas nixed that; the team, he said, needed to have a conversation before they took such a step. Then the next week another player asked about Kaepernick, and that led to the squad having a dialogue. Says Thomas: “We talked it out. What was [Kaepernick] doing? Why was he doing it? What does that mean to them? A lot of the kids said, ‘I don’t quite understand it.’ So we talked about the national anthem’s third verse and what that third verse really means. I had them read it out loud and told them: ‘You tell me what it means.’ Young men always ask, ‘What do you think?’ but my job is to help them become critical thinkers, not think for them. I said, ‘What do you think? Let’s read it out loud until you have a greater understanding.’ Each individual came to the belief that, hey, when they’re talking about these liberties and justices, they’re not speaking about me.”

The third verse, never sung before sporting events, reads in part:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave

This was in reference to the enslaved Black Americans who, promised freedom by the British, escaped bondage and joined the British army in the War of 1812. The anthem’s writer, Francis Scott Key, by many interpretations, was taking triumphant joy in the deaths of the enslaved. (This “joy” may have been influenced by the fact that Key was himself a slave owner.) In the last two lines, Key takes a wrecking ball to irony by declaring that the escaped enslaved people killed on the battlefield while fighting for their liberation is further proof of the glory of the “land of the free and the home of the brave.” As journalist Jon Schwarz wrote: “Maybe it’s all ancient, meaningless history. Or maybe it’s not, and Kaepernick is right, and we really need a new national anthem.”

The Garfield players, armed with this history, were ready to take that knee. Was Thomas nervous before they did it? He says, “No, I wasn’t—because, to be honest, I didn’t understand the gravity of the situation. I don’t think anyone understood what lay ahead or what would come from this. I saw it as an educational opportunity, to stand by and support these young men as they grow and find themselves. I didn’t think it was a big deal. The kids felt like doing something righteous, and what type of educator would I be if I didn’t support that? They weren’t hurting anyone. It wasn’t damaging anything. It wasn’t disrespectful. It wasn’t harmful. I just saw that these kids strongly believe this. This is what it is. If I’m wrong, then I’m wrong, but I’m supporting my kids.”

The backlash against Garfield came from all corners. “We had death threats,” Thomas says. “The kids were told that they were never going to get into college. People said they would do everything they could to make sure they wouldn’t get in through admissions. I was called every name in the book. And my tires were slashed at my house. This is my home. My wife and kids are there. My residence! I had to move because people knew where I lived.”

The way Thomas describes it, the district, Seattle Public Schools, felt the backlash and wanted Garfield’s football team to stop kneeling. They blamed Thomas, he says, and he paid for it with his job. First they charged him with a bogus recruiting violation, of which he was quickly cleared, and then the school tried to change his job title. Eventually, the harassment became too much and Thomas left the school to which he had dedicated so much of his life. “They were definitely trying to force me out, one way or the other,” he says. (Representatives for Seattle Public Schools and Garfield High declined to comment.)

Michael Zagaris/San Francisco 49ers/Getty Images

Now Joey Thomas is far from the place he called home, working at Florida Atlantic University, where he’s the receivers coach. “Obviously, the stance we took was unpopular,” he says. “Do I think it’s hurt me professionally? Without question. Was I hesitant to [talk about it]? Without question. But right is right and wrong is wrong. Am I still concerned about backlash at this point? Yeah, of course I am, because I already experienced it. It’s been shown to me what can happen.”

Thomas says of his players, “Everybody’s proud they did it, because we understand in hindsight that we were part of history. But it’s very important for people to understand: We didn’t know it was going to be like this. We didn’t plan on it being like this. We were just Garfield. We were just a high school in Seattle, standing for what we believed in. Before we knew it, we were in USA Today, the L.A. Times, Time magazine. ... Who saw that coming? The misconception was that we wanted the attention. Man, we didn’t ask for any of that. I sure didn’t ask to be catapulted to the front seat. But I think it was a comfortable narrative for people to push.

“Here’s the key: [Kneeling] was a student-led thing. But it was convenient for the powers that be to say it was coach-led, because then they’re able to give it a face. When it’s student-led, you can’t do that. And as a coach, you can’t do anything but support your kids. So, I think there was a conscious effort to deface what was going on and put a spin on it. In the end, that’s what cost me. But, hey, I would do it again. I’m always going to fight for what I believe in, but pushing what I believe was never the goal. The intention was to show these young men that they have a voice, that they are important, that they matter.”

Being attacked from all corners also brought the team and the school together. “Even though we did get support from everybody in our community, there was a long period of time when we were lonely and we were by ourselves,” says Thomas. “I think it’s always easier when people see other people supporting—they jump on the bandwagon. But there were some lonely days, some lonely weeks. Before it was popular to kneel with Kap, we were there. And, believe me, it was quite unpopular.”

Jelani Howard was part of that team. Seeing the gentrification taking place throughout Seattle—the creation of wealthy neighborhoods where he was clearly not wanted—was something that changed him when he was growing up. Like so many young people in what we could call “Generation Trayvon,” he hurtled toward becoming a changemaker when Trayvon Martin was murdered by George Zimmerman. “That’s when I started realizing, Oh, this is actually real,” Howard says. “Before that, I never thought of police brutality or anything like that. That’s when I really opened my eyes.”

Howard has his own story about how Garfield made its small piece of history. “It all started,” he says, “because coach Thomas used to have these talks with us in the summer about what’s going on in the world, before we’d even go to practice or watch film. [Donald] Trump was running for office and we were talking about what was going on. Then, during preseason, Kaepernick took a knee, and after that game we talked about why he did it. That led us on to other conversations. We started talking about how other verses of the national anthem talked about killing slaves. It all started with conversations ... connecting it to what’s going on in the world.”

Buy The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World

After the high schoolers took a knee, Kaepernick spoke about it to The Seattle Times, saying: “We have a younger generation that sees these issues and want to be able to correct them. I think that’s amazing. I think it shows the strength, the character and the courage of our youth. Ultimately, they’re going to be needed to help make this change.”

What made Garfield exceptional—and what caught Kaepernick’s attention—was that, as Howard remembers, “It was the whole team—even the managers and cheerleaders started taking a knee.” It all made national news, but that meant a national backlash. “At first we had a Facebook picture of our entire team. People would comment on it, saying nasty or disrespectful things. Then there was the one morning where [coach Thomas] didn’t show up and everybody was just confused. He finally got there like an hour late, and he told us that somebody had slashed his tires. That’s when everybody knew: Wow, this is real. People are really mad about us doing this.”

As for regrets, Howard says, “I have none. It’s something that I’ll always be able to tell my kids about. I did something I will always remember. ... Nobody thought that 15-, 16-, 17-year-old kids would be able to help lead a movement. I have no regrets because we had a motivation: We wanted to see social equality for everybody because we live in a society where, if you’re a person of color, you’re already on the back burner. If there’s a Black person and a white person who have the same college degree, same everything, that white person will make more than that Black person, just based on race. That just doesn’t sit right with me. I want to be able to change that for the next generation.”

Howard has advice for others thinking about stepping forward and speaking out: “You have a voice and you should use it and you shouldn’t be scared of what people will say or what will happen. There are people who went before us, who went through way worse things than we’re going through now.”

Once the football team took a knee, it spread to other sports at Garfield High. Janelle Gary was on the softball team that joined in. She had played on a select team growing up, and she remembers how an umpire once made a snide remark about her being one of the few Black girls on the field. She was only 10 at the time. “That is something I’ll never forget,” she says.

Police violence, too, was something Gary was made aware of at a young age. But it wasn’t until social media highlighted the killing of Martin—and highlighted other Black people who’ve been affected by racial violence and police brutality—that it hit home. “Actually watching the videos myself,” she says, “brought it into reality for me.”

Ira L. Black/Corbis/Getty Images

Gary and her team at Garfield decided to protest during the anthem in part because of the backlash the football team had taken—especially Thomas. “People were threatening him and his children,” she remembers. “We wanted to stand up by taking a knee. ... We wanted to show solidarity, not only with Colin Kaepernick, but also to support our football team—to show that Garfield believes in this together.”

She describes a team that “was the most diverse that made it to state; an inner-city school [that] had the most people of color,” and whose students and faculty are often on the front lines of social justice movements in Seattle. The softball team was united in its decision to take a knee.

“During [that first] game,” Gary says, “one parent was antagonizing us and making comments every time we went up to bat. That was a lot for us to take in, having parents from the stands yell at you. [Afterward, on] our lunch break, a bunch of parents from other schools found us and went out of their way to keep on yelling: ‘Shame on you, Garfield! Shame on you!’ No one asked why we were doing it. They just attacked us. It was really hard, at that age. We were very emotional. We didn’t think people would attack kids like that.”

If Gary could do it all over again, she says she would. “People say negative things to try to scare you, but if you’re able to persevere through that, like in the days of the civil rights movement, you’re going to see more change. They are trying to stop a movement, because they know how big it can become.”

Two years after kneeling during the national anthem, Gary and the Garfield softball team won the state championship. “I think that was our sweet revenge,” she says. “I did appreciate being the first inner-city school to win state.”

Gary also helped start an organization, New Generation, after the death of Charleena Lyles, a Seattle Public Schools mother who was shot and killed by the police. New Generation organized demonstrations and raised money for Lyles’s family, and the group worked closely with former NFL player Michael Bennett to make sure Lyles’s name wouldn’t be forgotten—“that people in our community know what’s going on,” Gary says.

Ron Hoskins/NBAE/Getty Images

Bigger picture, Gary ponders the political impact of Kaepernick and his protest, and she says: “Many people don’t like him, but you have to think that people didn’t like Dr. Martin Luther King or Malcolm X in their time, either, because they knew [these men] were starting a revolution. [Kaepernick] is getting people to talk, so you’re going to have people who love him and people who hate him. But I believe in 20 years he’ll be seen as one of the greatest. He’s given people hope. If it wasn’t for him, I really don’t think there’d be a conversation.

“Sometimes when you stick up for what you believe in, it upsets people. When they crack down on you taking a knee, or raising a fist, it shows they don’t want you to have hope. Especially being young, you need that hope to keep on going. ... I’m glad I experienced this all at a young age, so now I have a better understanding of what people are like. I’m glad we [knelt], and I’m glad we had someone like Colin Kaepernick to give us the courage to do that.”

• Tom Brady's Forgotten Rookie Year

• Dak Prescott's Heal Turn

• The Falcons, Depression and Me

0 Comments