To eradicate counterfeits, MLB went all in on authentication. It’s paying off.

The major league ballpark has really only one job that demands keeping an eye on the ball.

The hitter should, of course. And the catcher, too. But for them, watching the baseball is a means to an end rather than an actual requirement. The umpire? Close, but he has limited jurisdiction; he isn’t asked to track the ball all over the diamond. If he’s working home plate his eyes are peeled to call pitches, but he doesn’t have to stay fixated on the ball for, say, a tag at second base. And while managers, fielders and fans are all looking on with varying degrees of attentiveness, they’re generally watching the game, which is very often different from watching the baseball. That leaves one very small group of observers who will never relax their gaze.

Tasked with certifying the authenticity of items from every game—including, naturally, lots and lots of baseballs—there are at least two authenticators at every major league contest from spring training through October. Their work receives added attention when it comes to a milestone home run or a big moment, such as the World Series. But they are in stadiums every single day, tracking notable objects, documenting them with an intricate note-taking system and tagging them in a way that escapes tampering. While their work is done largely behind the scenes, it has become a more visible, ingrained part of the sport in recent years, and as MLB’s authentication program marks its 20th anniversary this season, the job is bigger than ever. What was once a laser-focused attempt to curb fake memorabilia is now a sprawling daily enterprise that tracks the journey of (almost) every single baseball.

Vaughn Ridley/Getty Images

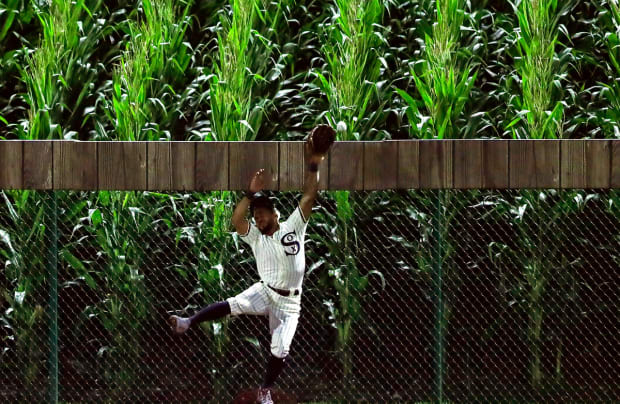

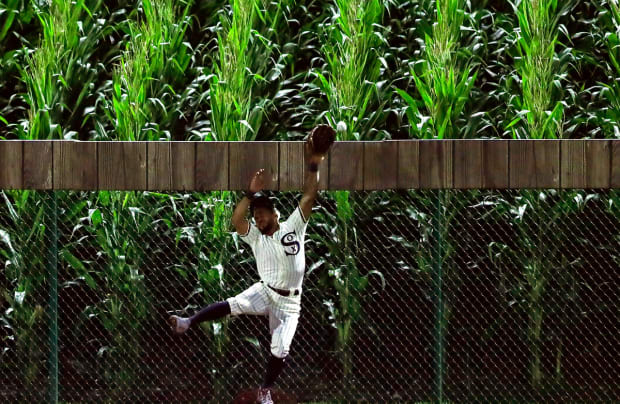

And more. The program’s legion of baseball detectives authenticate upwards of half a million objects each year, including jerseys, caps, belts, cleats, bases, lineup cards, stadium dirt—you name it. They have verified the legitimacy of at least one set of urinals (following the demolition of the Cardinals’ old Busch Memorial Stadium in 2005) and a few stalks of corn (from the Field of Dreams game last month in Dyersville, Iowa). Some of these keepsakes end up in the Baseball Hall of Fame, others go to individual club archives or players’ rec rooms, and many more are made available to fans. (The urinals, though perhaps historic in their own way, went to a private collector, not to Cooperstown.) Altogether, the program is part security initiative, part historical documentation, part revenue engine. And it starts with the authenticators, embedded in every park, who try never to take their eyes off the ball.

“It’s in the way you take notes, the way you watch,” says MLB’s director of authentication, Michael Posner, trying to encapsulate his field. “You watch a game very differently than you’ve ever watched a game before.”

It started with the FBI. In April 2000 the bureau announced that it had completed the first phase of what it called

Operation Bullpen, a national probe into forged autographs and other fake sports memorabilia.Investigators estimated that at least half of the items for sale across the industry were in some way counterfeit—possibly much more than that, even up to 90%. If you had what you believed to be a signed, game-used Mickey Mantle bat … well, no, the odds were that you actually didn’t. And while the FBI was in charge of taking down sham dealers, leading to 63 separate charges and convictions, MLB, really, was at the center of everything. The national pastime, after all, had inspired the operation’s name. Padres star Tony Gwynn and Cardinals slugger Mark McGwire even assisted in the investigation by verifying their signatures for the FBI and pointing out fakes. (Gwynn was spurred to action after he walked into an official Padres gift shop in Encinitas, Calif., and found that even in a team store there were alleged Tony Gwynn–autographed items that he knew he’d never signed.) The league, though, had no system for verifying memorabilia at scale, and after such a public embarrassment, a means of weeding out obvious fakes was needed. So MLB’s leaders decided to take action.

Earl Cryer/ZUMA Press

Behold, the authentication program.

When it all began, in 2001, there was no blueprint for how, exactly, one would crack down. No other league had a program of the size that MLB was eyeing. (And baseball’s version today is far more robust than those of other top leagues.) “The first years we were just trying to clean up something that had become a really big problem,” says Posner, who has been with the program almost since the beginning. By ’06, after a few seasons of working out the kinks, MLB had landed on the basic outline of the operation that’s still in use today. Which looks like this:

Baseball’s authenticators are required to have experience in law enforcement. Their work is like evidence collection in that it relies on a chain of custody. They must trace where and how an object changed hands throughout a contest in order to verify it as game-used. (The best authenticators, Posner says, tend to have worked as forensic accountants, where record-keeping and attention to detail are crucial.) The jobs are never openly listed; candidates are recruited by word of mouth and hired through a third-party company, and they undergo extensive training, with a goal of limiting turnover. Many of the 220 authenticators who work with MLB today have been around since almost the beginning.

Each club has its own director of authentication, and some team programs are more robust than others, so that the exact shape of the work can vary from stadium to stadium. But the basics are similar. Every day begins with a meeting to go over the game plan: Is there a player or some other personnel who’s close to a statistical milestone of any sort? Could anyone be making their major league debut? Is there something else special about the game—a themed jersey, an addition to the coaching staff—or anything otherwise memorable about the environment?

Those items join a list of everyday fare: lineup cards, broken bats, perhaps some bases or jerseys. … And dozens and dozens of baseballs. Those balls make up the majority of the items handled by the program each year. They also show the profound, exacting rigor of its system.

The chain of custody can be easy enough to follow for a hat or for a set of bases—items that largely remain attached to a specific person or, better, stay stationary on the field. There isn’t usually much to track. But for a baseball? A ball is involved in every single play, changing hands as a matter of course, ever a risk to leave the field and slip into the crowd. To authenticate a game-used ball is to bear witness to each and every moment of its major league life—an act of constant vigilance.

Taylor Baucom/MLB/Getty Images

“You’re so focused on the baseball as an authenticator that you really don’t pick up some of the other things going on,” Posner says. “You have to be very involved for every pitch.”

Perched beside the dugouts, authenticators take notes as they track each ball, waiting for the moment when it is discarded or swapped out or otherwise removed from the field. If this part of the job seems redundant in the age of Statcast, note: Those cameras and radars can determine launch angle and exit velocity down to the decimal point, but they can’t distinguish between one cowhide orb and the next. That’s still the domain of the authenticator alone. And it’s an area where human institutional knowledge helps. Skilled authenticators will remember that Pitcher A likes to ask for a new ball every time he gives up a hit, or that Pitcher B has a groundball-heavy style that will keep them busy with infield action.

Once a ball leaves a game, the physical stage of authentication begins. If an authenticator is satisfied that they have chronicled a ball’s every move, they’ll retrieve it, either themself or through a ball boy or ball girl. They’ll affix a tiny silver sticker—a hologram bearing a unique string of letters and numbers—to its surface. And they’ll log their record of the ball’s life in a unique MLB system, akin to an app.

As recently as five years ago, the process would have stopped at that point, but now there’s a new wrinkle: The relevant pitches and plays are matched with the corresponding data from Statcast. Today, if you were to type the code on that little sticker into MLB’s authentication database it would unlock a record, not just of the ball’s final play, but of all its plays—“actually going into the detail of This is the pitcher that threw it, this was the batter, this was the speed it was thrown at, this was the exit velocity,” says Gavin Werner, director of retail and authentication for the Giants. “It creates this deeper, richer picture of how that baseball was being used. I think you can really remember it in a more significant way.”

And that’s just for one ball. Repeat 50 times per game, or more, and add in at least one set of bases and lineup cards. That’s on an average night. But a perfect game? A milestone hit? A special jersey collection? You’re easily looking at more than 100 items authenticated on a given game day.

The program ensures that someone documents the artifacts attached to every surprise bit of baseball history—each no-hitter and multi-home-run game and unassisted triple play—and from every day of baseball, period. And this authentication has become the standard for any sale or display of memorabilia. Even if a player has something of his own that he just wants to keep for posterity, the importance of getting that little sticker is now widely understood. (Technically, team-issued objects like jerseys and hats belong to each club, whereas personal gear like batting gloves or cleats belong to players—but teams generally try to build a two-way street so there’s no dispute over who gets to keep a given item. “Players know we’re going to put them first; if there’s anything significant, we will always try to honor their requests,” says Werner, whose Giants share a cut of any authenticated item that is sold with the player whose name is on it, even if the item was originally provided by the team, like a jersey.)

Juan DeLeon/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

In the end, this all adds up to one dramatic blow to the fake-game-used-merchandise market. (Posner estimates that just one phony has come across his desk in the last five years.) In addition to chasing out the counterfeiters, however, the sheer volume of items catalogued has created a notable retail force for teams and for the league, which Posner sums up as “a very nice offshoot of cleaning up the fraud.” If an object is authenticated but isn’t requested by a player, the club archive or the Hall of Fame—most objects are not—it will often be made available for purchase at auction or by direct sale. And in its tiny silver sticker it will carry the story of its major league life.

There is one common situation in which it’s all but impossible to maintain a chain-of-custody record for a piece of baseball history: when it flies into the crowd. The balls with the most exciting fates, in other words, are often the ones least likely to get authenticated.

“We have more than a few videos of people switching out baseballs,” Posner says, explaining how stadium scrums can stymie the authentication process on home runs. “People have [balls] from batting practice, or they bring in a ball and they want to keep the real one and throw back the fake one.”

As a result, authenticated home run balls are especially hard to come by. Dingers are generally stickered only when the ball ricochets out of the stands, back onto the field, in view the whole time. One recent exception: During the 2020 pandemic season, with its empty stadiums, the majority of home runs were authenticated for the first time.

Even then, though, the chain-of-custody standards ensured that authentication could be tricky. Jordan Field, the Tigers’ director of player relations and authentication, recalls being told before a home game against the Brewers last September that Milwaukee slugger Ryan Braun was trying to collect as many of his own authenticated home run balls as possible, for his personal collection, as his career winded down. In the seventh inning Braun launched one toward the Comerica Park stands, which were swept clean after batting practice, leaving Field with what should have been an easy pickup. Instead, Field watched as the ball soared toward the home bullpen … and directly into a trash can.

Which is how Field ended up leaning over the left-field railing with an odd request for Detroit’s pitchers below: Could one of you please reach into that trash can? And if you find one baseball in there—only one, of course, because Braun’s ball couldn’t be authenticated if there were two—could you please pass it up?

The trash can held just the one baseball. Field had it authenticated. And Braun got his memento.

Reese Strickland/USA Today Sports

Those specific circumstances seem unlikely to recur. And with fans in the stands again, the authentication of home run balls is once more a rarity. Still, Posner and his crew wondered last month whether there might be an opportunity for one more unobstructed home run haul, at the Field of Dreams game in Iowa, where long balls would disappear into the corn rather than into a crowd of potential collectors. Alas, “the way the corn was planted, the immensity of it and the height of it, the ball would literally just disappear,” he laments. In the end, the authenticators did find baseballs among the stalks, but—such are their standards—they couldn’t be completely sure that any given ball was a specific home run, not one from batting practice. And so Posner & Co. settled instead on authenticating some of the corn itself.

Another exception in the aversion to authenticating home run balls: the occasion of a major milestone, like when a player reaches No. 500. For the Tigers’ Miguel Cabrera, the process worked like this: After he hit No. 499, on Aug. 11, baseballs stenciled with an M and a serial number were cycled in for each plate appearance so they could be easily recognized but also to establish an order in which they would be used. Each ball also bore a unique marking that could be seen only under something akin to a blacklight. (The specific fluid and light used for this process remains an MLB secret. “The covert marking you cannot find—I guarantee you—with a blacklight. It won’t work,” says Posner.) The ball boy or ball girl would visit the umpire before and after each of Cabrera’s plate appearances, dropping off and picking up the special balls. The pitcher could not throw them to any other batter.

All of which ensured that authenticators would be able to verify the ball. But first they would have to retrieve it from whoever caught it, which has occasionally proved tricky in the past.

Cabrera hit No. 500 on Aug. 22, against the Blue Jays in Toronto. For every game of their road trip the Tigers had reserved an empty suite, where they could host a potential home-run-catching fan, both for security purposes (no one wanted to see the fan get swarmed), and for a chance at an intimate—and, ideally, persuasive—meet-and-greet with the slugger.

“We were not prepared to purchase the baseball,” says Field. “The plan was to create an experience for the fan, with Miguel, that would have been so memorable that presenting the baseball to him in person after the game would have been an easy decision.”

And it worked. The ball went back to Cabrera and the Tigers—after authenticators had verified it and applied a hologram sticker, of course. That afternoon, though, the ball itself was just one of 183 items authenticated, including a bucket of dirt from the right-handed batter’s box, all of the unused marked balls, every champagne bottle from the postgame clubhouse celebration and everything worn by Cabrera. (Detroit’s equipment manager had packed an extra No. 24 uniform—all the way down to the belt—for the road trip, knowing that Cabrera would have to give his up as soon as he hit No. 500.)

Courtesy of the Detroit Tigers

The same process is followed in the event of a 600th or a 700th home run. After that “you start getting into Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron territory—we start to do a bit more marking,” says Posner. It’s also used when someone approaches 3,000 hits, which means that Field and Cabrera, who’s sitting on 2,964, will likely be doing this all over again next year.

These are the kinds of massive moments the program was made for. But asked for his favorite authentication of the summer, Posner throws a curveball. When White Sox reliever Liam Hendriks was miked up at this summer’s All-Star Game in Denver, fans on television got to hear him pitch through a creative string of profanities. They also got to hear how he reacted to his first strikeout.

“I wanna get that ball authenticated!” he yelled as the baseball returned to him after going around the horn. Hendriks motioned for a new one, tapped the surface of the old one, tossed it in the direction of the authenticator by the dugout and hollered: “Hey! Little sticker!”

• Colin Kaepernick Went First. They Were Second

• The Falcons, Depression and Me

• Dak Prescott's Heal Turn

To eradicate counterfeits, MLB went all in on authentication. It’s paying off.

The major league ballpark has really only one job that demands keeping an eye on the ball.

The hitter should, of course. And the catcher, too. But for them, watching the baseball is a means to an end rather than an actual requirement. The umpire? Close, but he has limited jurisdiction; he isn’t asked to track the ball all over the diamond. If he’s working home plate his eyes are peeled to call pitches, but he doesn’t have to stay fixated on the ball for, say, a tag at second base. And while managers, fielders and fans are all looking on with varying degrees of attentiveness, they’re generally watching the game, which is very often different from watching the baseball. That leaves one very small group of observers who will never relax their gaze.

Tasked with certifying the authenticity of items from every game—including, naturally, lots and lots of baseballs—there are at least two authenticators at every major league contest from spring training through October. Their work receives added attention when it comes to a milestone home run or a big moment, such as the World Series. But they are in stadiums every single day, tracking notable objects, documenting them with an intricate note-taking system and tagging them in a way that escapes tampering. While their work is done largely behind the scenes, it has become a more visible, ingrained part of the sport in recent years, and as MLB’s authentication program marks its 20th anniversary this season, the job is bigger than ever. What was once a laser-focused attempt to curb fake memorabilia is now a sprawling daily enterprise that tracks the journey of (almost) every single baseball.

Vaughn Ridley/Getty Images

And more. The program’s legion of baseball detectives authenticate upwards of half a million objects each year, including jerseys, caps, belts, cleats, bases, lineup cards, stadium dirt—you name it. They have verified the legitimacy of at least one set of urinals (following the demolition of the Cardinals’ old Busch Memorial Stadium in 2005) and a few stalks of corn (from the Field of Dreams game last month in Dyersville, Iowa). Some of these keepsakes end up in the Baseball Hall of Fame, others go to individual club archives or players’ rec rooms, and many more are made available to fans. (The urinals, though perhaps historic in their own way, went to a private collector, not to Cooperstown.) Altogether, the program is part security initiative, part historical documentation, part revenue engine. And it starts with the authenticators, embedded in every park, who try never to take their eyes off the ball.

“It’s in the way you take notes, the way you watch,” says MLB’s director of authentication, Michael Posner, trying to encapsulate his field. “You watch a game very differently than you’ve ever watched a game before.”

It started with the FBI. In April 2000 the bureau announced that it had completed the first phase of what it called Operation Bullpen, a national probe into forged autographs and other fake sports memorabilia.

Investigators estimated that at least half of the items for sale across the industry were in some way counterfeit—possibly much more than that, even up to 90%. If you had what you believed to be a signed, game-used Mickey Mantle bat … well, no, the odds were that you actually didn’t. And while the FBI was in charge of taking down sham dealers, leading to 63 separate charges and convictions, MLB, really, was at the center of everything. The national pastime, after all, had inspired the operation’s name. Padres star Tony Gwynn and Cardinals slugger Mark McGwire even assisted in the investigation by verifying their signatures for the FBI and pointing out fakes. (Gwynn was spurred to action after he walked into an official Padres gift shop in Encinitas, Calif., and found that even in a team store there were alleged Tony Gwynn–autographed items that he knew he’d never signed.) The league, though, had no system for verifying memorabilia at scale, and after such a public embarrassment, a means of weeding out obvious fakes was needed. So MLB’s leaders decided to take action.

Earl Cryer/ZUMA Press

Behold, the authentication program.

When it all began, in 2001, there was no blueprint for how, exactly, one would crack down. No other league had a program of the size that MLB was eyeing. (And baseball’s version today is far more robust than those of other top leagues.) “The first years we were just trying to clean up something that had become a really big problem,” says Posner, who has been with the program almost since the beginning. By ’06, after a few seasons of working out the kinks, MLB had landed on the basic outline of the operation that’s still in use today. Which looks like this:

Baseball’s authenticators are required to have experience in law enforcement. Their work is like evidence collection in that it relies on a chain of custody. They must trace where and how an object changed hands throughout a contest in order to verify it as game-used. (The best authenticators, Posner says, tend to have worked as forensic accountants, where record-keeping and attention to detail are crucial.) The jobs are never openly listed; candidates are recruited by word of mouth and hired through a third-party company, and they undergo extensive training, with a goal of limiting turnover. Many of the 220 authenticators who work with MLB today have been around since almost the beginning.

Each club has its own director of authentication, and some team programs are more robust than others, so that the exact shape of the work can vary from stadium to stadium. But the basics are similar. Every day begins with a meeting to go over the game plan: Is there a player or some other personnel who’s close to a statistical milestone of any sort? Could anyone be making their major league debut? Is there something else special about the game—a themed jersey, an addition to the coaching staff—or anything otherwise memorable about the environment?

Those items join a list of everyday fare: lineup cards, broken bats, perhaps some bases or jerseys. … And dozens and dozens of baseballs. Those balls make up the majority of the items handled by the program each year. They also show the profound, exacting rigor of its system.

The chain of custody can be easy enough to follow for a hat or for a set of bases—items that largely remain attached to a specific person or, better, stay stationary on the field. There isn’t usually much to track. But for a baseball? A ball is involved in every single play, changing hands as a matter of course, ever a risk to leave the field and slip into the crowd. To authenticate a game-used ball is to bear witness to each and every moment of its major league life—an act of constant vigilance.

Taylor Baucom/MLB/Getty Images

“You’re so focused on the baseball as an authenticator that you really don’t pick up some of the other things going on,” Posner says. “You have to be very involved for every pitch.”

Perched beside the dugouts, authenticators take notes as they track each ball, waiting for the moment when it is discarded or swapped out or otherwise removed from the field. If this part of the job seems redundant in the age of Statcast, note: Those cameras and radars can determine launch angle and exit velocity down to the decimal point, but they can’t distinguish between one cowhide orb and the next. That’s still the domain of the authenticator alone. And it’s an area where human institutional knowledge helps. Skilled authenticators will remember that Pitcher A likes to ask for a new ball every time he gives up a hit, or that Pitcher B has a groundball-heavy style that will keep them busy with infield action.

Once a ball leaves a game, the physical stage of authentication begins. If an authenticator is satisfied that they have chronicled a ball’s every move, they’ll retrieve it, either themself or through a ball boy or ball girl. They’ll affix a tiny silver sticker—a hologram bearing a unique string of letters and numbers—to its surface. And they’ll log their record of the ball’s life in a unique MLB system, akin to an app.

As recently as five years ago, the process would have stopped at that point, but now there’s a new wrinkle: The relevant pitches and plays are matched with the corresponding data from Statcast. Today, if you were to type the code on that little sticker into MLB’s authentication database it would unlock a record, not just of the ball’s final play, but of all its plays—“actually going into the detail of This is the pitcher that threw it, this was the batter, this was the speed it was thrown at, this was the exit velocity,” says Gavin Werner, director of retail and authentication for the Giants. “It creates this deeper, richer picture of how that baseball was being used. I think you can really remember it in a more significant way.”

And that’s just for one ball. Repeat 50 times per game, or more, and add in at least one set of bases and lineup cards. That’s on an average night. But a perfect game? A milestone hit? A special jersey collection? You’re easily looking at more than 100 items authenticated on a given game day.

The program ensures that someone documents the artifacts attached to every surprise bit of baseball history—each no-hitter and multi-home-run game and unassisted triple play—and from every day of baseball, period. And this authentication has become the standard for any sale or display of memorabilia. Even if a player has something of his own that he just wants to keep for posterity, the importance of getting that little sticker is now widely understood. (Technically, team-issued objects like jerseys and hats belong to each club, whereas personal gear like batting gloves or cleats belong to players—but teams generally try to build a two-way street so there’s no dispute over who gets to keep a given item. “Players know we’re going to put them first; if there’s anything significant, we will always try to honor their requests,” says Werner, whose Giants share a cut of any authenticated item that is sold with the player whose name is on it, even if the item was originally provided by the team, like a jersey.)

Juan DeLeon/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

In the end, this all adds up to one dramatic blow to the fake-game-used-merchandise market. (Posner estimates that just one phony has come across his desk in the last five years.) In addition to chasing out the counterfeiters, however, the sheer volume of items catalogued has created a notable retail force for teams and for the league, which Posner sums up as “a very nice offshoot of cleaning up the fraud.” If an object is authenticated but isn’t requested by a player, the club archive or the Hall of Fame—most objects are not—it will often be made available for purchase at auction or by direct sale. And in its tiny silver sticker it will carry the story of its major league life.

There is one common situation in which it’s all but impossible to maintain a chain-of-custody record for a piece of baseball history: when it flies into the crowd. The balls with the most exciting fates, in other words, are often the ones least likely to get authenticated.

“We have more than a few videos of people switching out baseballs,” Posner says, explaining how stadium scrums can stymie the authentication process on home runs. “People have [balls] from batting practice, or they bring in a ball and they want to keep the real one and throw back the fake one.”

As a result, authenticated home run balls are especially hard to come by. Dingers are generally stickered only when the ball ricochets out of the stands, back onto the field, in view the whole time. One recent exception: During the 2020 pandemic season, with its empty stadiums, the majority of home runs were authenticated for the first time.

Even then, though, the chain-of-custody standards ensured that authentication could be tricky. Jordan Field, the Tigers’ director of player relations and authentication, recalls being told before a home game against the Brewers last September that Milwaukee slugger Ryan Braun was trying to collect as many of his own authenticated home run balls as possible, for his personal collection, as his career winded down. In the seventh inning Braun launched one toward the Comerica Park stands, which were swept clean after batting practice, leaving Field with what should have been an easy pickup. Instead, Field watched as the ball soared toward the home bullpen … and directly into a trash can.

Which is how Field ended up leaning over the left-field railing with an odd request for Detroit’s pitchers below: Could one of you please reach into that trash can? And if you find one baseball in there—only one, of course, because Braun’s ball couldn’t be authenticated if there were two—could you please pass it up?

The trash can held just the one baseball. Field had it authenticated. And Braun got his memento.

Reese Strickland/USA Today Sports

Those specific circumstances seem unlikely to recur. And with fans in the stands again, the authentication of home run balls is once more a rarity. Still, Posner and his crew wondered last month whether there might be an opportunity for one more unobstructed home run haul, at the Field of Dreams game in Iowa, where long balls would disappear into the corn rather than into a crowd of potential collectors. Alas, “the way the corn was planted, the immensity of it and the height of it, the ball would literally just disappear,” he laments. In the end, the authenticators did find baseballs among the stalks, but—such are their standards—they couldn’t be completely sure that any given ball was a specific home run, not one from batting practice. And so Posner & Co. settled instead on authenticating some of the corn itself.

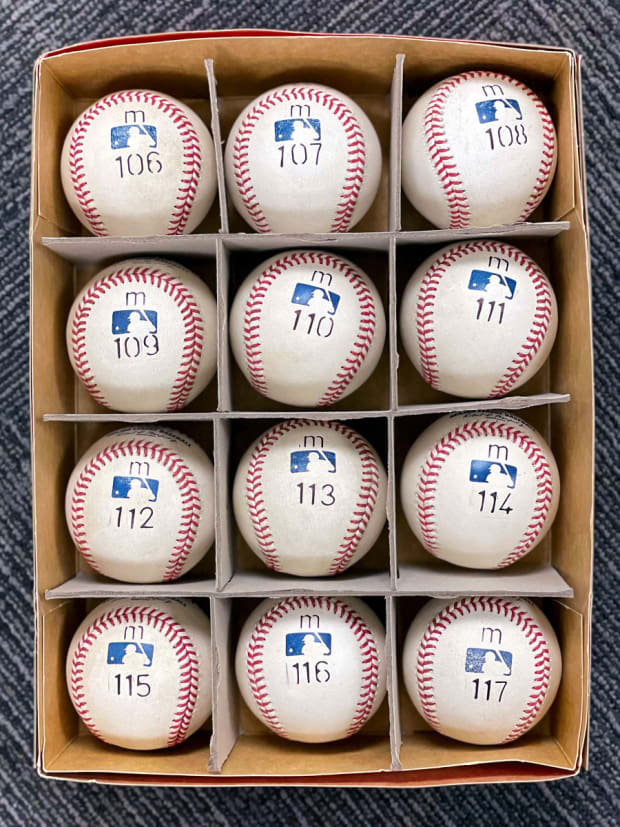

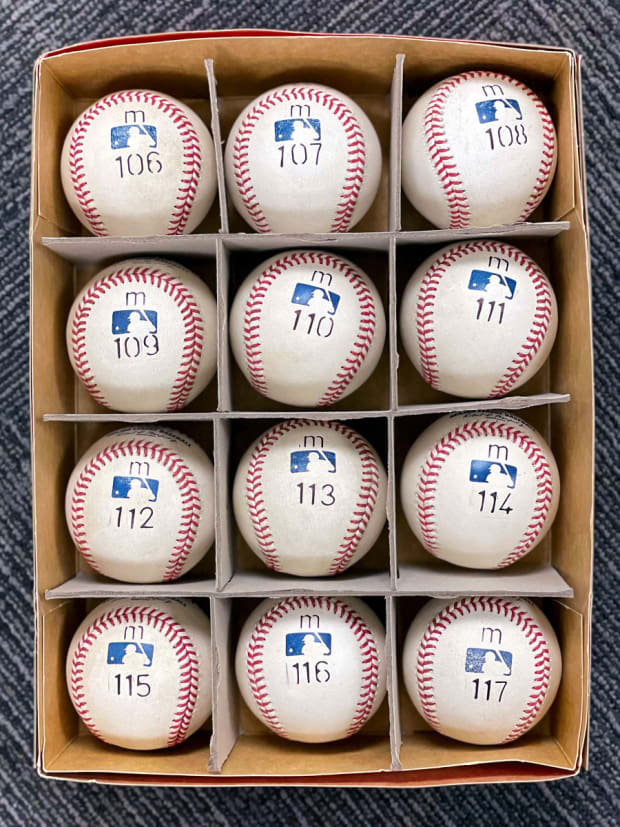

Another exception in the aversion to authenticating home run balls: the occasion of a major milestone, like when a player reaches No. 500. For the Tigers’ Miguel Cabrera, the process worked like this: After he hit No. 499, on Aug. 11, baseballs stenciled with an M and a serial number were cycled in for each plate appearance so they could be easily recognized but also to establish an order in which they would be used. Each ball also bore a unique marking that could be seen only under something akin to a blacklight. (The specific fluid and light used for this process remains an MLB secret. “The covert marking you cannot find—I guarantee you—with a blacklight. It won’t work,” says Posner.) The ball boy or ball girl would visit the umpire before and after each of Cabrera’s plate appearances, dropping off and picking up the special balls. The pitcher could not throw them to any other batter.

All of which ensured that authenticators would be able to verify the ball. But first they would have to retrieve it from whoever caught it, which has occasionally proved tricky in the past.

Cabrera hit No. 500 on Aug. 22, against the Blue Jays in Toronto. For every game of their road trip the Tigers had reserved an empty suite, where they could host a potential home-run-catching fan, both for security purposes (no one wanted to see the fan get swarmed), and for a chance at an intimate—and, ideally, persuasive—meet-and-greet with the slugger.

“We were not prepared to purchase the baseball,” says Field. “The plan was to create an experience for the fan, with Miguel, that would have been so memorable that presenting the baseball to him in person after the game would have been an easy decision.”

And it worked. The ball went back to Cabrera and the Tigers—after authenticators had verified it and applied a hologram sticker, of course. That afternoon, though, the ball itself was just one of 183 items authenticated, including a bucket of dirt from the right-handed batter’s box, all of the unused marked balls, every champagne bottle from the postgame clubhouse celebration and everything worn by Cabrera. (Detroit’s equipment manager had packed an extra No. 24 uniform—all the way down to the belt—for the road trip, knowing that Cabrera would have to give his up as soon as he hit No. 500.)

Courtesy of the Detroit Tigers

The same process is followed in the event of a 600th or a 700th home run. After that “you start getting into Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron territory—we start to do a bit more marking,” says Posner. It’s also used when someone approaches 3,000 hits, which means that Field and Cabrera, who’s sitting on 2,964, will likely be doing this all over again next year.

These are the kinds of massive moments the program was made for. But asked for his favorite authentication of the summer, Posner throws a curveball. When White Sox reliever Liam Hendriks was miked up at this summer’s All-Star Game in Denver, fans on television got to hear him pitch through a creative string of profanities. They also got to hear how he reacted to his first strikeout.

“I wanna get that ball authenticated!” he yelled as the baseball returned to him after going around the horn. Hendriks motioned for a new one, tapped the surface of the old one, tossed it in the direction of the authenticator by the dugout and hollered: “Hey! Little sticker!”

• Colin Kaepernick Went First. They Were Second

• The Falcons, Depression and Me

• Dak Prescott's Heal Turn

0 Comments